Christianity defines itself as a religion of peace, not insofar as the Messiah brought and brings no disruption, but insofar as violence is reserved for specifically delineated circumstances; it is not to be accepted easily, and only to be accepted after great prayer and fasting. We might remember that Mattathias, before he kills the Jew for apostasy, lifts his voice up in prayerful lamentation:

Woe is me! Why was I born

to see the ruin of my people,

the ruin of the holy city—

To dwell there

as it was given into the hands of enemies,

the sanctuary into the hands of strangers?

Her temple has become like a man disgraced,

her glorious vessels carried off as spoils,

Her infants murdered in her streets,

her youths by the sword of the enemy.

What nation has not taken its share of her realm,

and laid its hand on her spoils?

All her adornment has been taken away.

Once free, she has become a slave.

We see our sanctuary laid waste,

our beauty, our glory.

The Gentiles have defiled them!

Why are we still alive? (1 Maccabees 2:7-13)

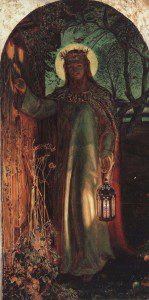

War is not the focus of the Gospels; the Jews expected a military messiah, and instead received a donkey-riding carpenter who hung out with prostitutes. He brought social division, intended toward the higher cohesion of the Body of Christ. It is in this light that we should read passages like this one:

Do not think that I have come to bring peace upon the earth. I have come to bring not peace but the sword. For I have come to set a man ‘against his father, a daughter against her mother, and a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law; and one’s enemies will be those of his household. Whoever loves father or mother more than me is not worthy of me, and whoever loves son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me; and whoever does not take up his cross and follow after me is not worthy of me. Whoever finds his life will lose it, and whoever loses his life for my sake will find it. (Matthew 10:34-39).

If Christ did not preach violence in any traditional sense, or if at minimum, violence is always a last resort, what then do Christians do when it would otherwise be so easy to take a side? Take the recent conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan. I find it hard to imagine a Christian whose heart doesn’t immediately go out to Armenia, the first Christian “state.” After over a millennium of Islamic pressure, last century’s genocide, and Soviet rule, Armenia could be called something of a martyr nation, still rich in faith after so many travails. It also has ties to Putin’s Russia, which, for better or worse, has become a favorite among certain culturally-minded Christians. Azerbaijan, by contrast, is a mostly Muslim country, in an age of increasing dislike of Islam among Westerners. It’s a larger country that could easily be conceived of as occupying the majority-Armenian territory over which the two country are fighting. Perhaps most difficultly, it enjoys strong ties to Turkey, with the Turkish government saying it would defend its ally if needed. These days, thanks to its foreign policy and domestic Islamization, Turkey is far from a Christian, or even just Western, favorite.

And yet, can we really say the Christian thing to do is to take sides in a primarily ethnic conflict, a series of skirmishes in which people are continuing to die? We do not know who started the fighting; both sides point the finger at the other. What we do know is that God’s children are suffering and dying, the poor people of a highly-mountainous, ex-Soviet region are facing economic, cultural, and existential destabilization. Even as our hearts pull us to defend one side, our true calling is to pray for all involved, to pray for God’s peace over a fractured and ailing part of the world. To be frank, regions immediately east of Turkey are not in need for any further social upheaval, unless it be the division left in the wake of the unifying movement of the Holy Spirit in the Body of Christ.

There are claims of a ceasefire; though it is doubtful one will come so quickly, we put our hopes in a swift end to unnecessary bloodshed.

In this sense, to be a peacemaking people is always to hold violence as a last resort, if a resort at all, to recognize that, for all the violence committed by human beings, there is the possibility of peace in the Body of Christ, in the Kingdom already among us. Such things are not easy, not at all. It is, perhaps, in the examples of the martyrs that we most recognize the paradoxical call of Christians to make peace in a non-Christian world. Here, I think of St. Théophane Vénard, who said, “Be merry, be really merry. The life of a true Christian should be an eternal jubilee, a prelude to the festival of eternity.” In fact, his bishop once wrote of him, “Though in chains, he is as gay as a little bird.” He is supposed to have gone to his execution singing psalms and hymns. This is what it means to be a peacemaking people: to be joyful and seek union where there is strife, to celebrate the Gospel, even in spite of the grossest sins of a fallen world.