Self-Interest gets spoken about quite a bit these days, whether in its economic or political form. And even when it’s not being invoked in the name of Adam Smith’s economic theories or Ayn Rand’s Objectivism, it sits behind much of what we discuss. Can people consent to have themselves killed by a physician? Must everyone vaccinate their children, if they believe not doing so to be right? Or, put most generally: should a person be able to do whatever he or she thinks best for his or her person and / or body?

But what if the entire discourse of self-interest misses the point? What if the idea of my own personal proclivities, understood in the broadest socio-political terms, is really foreign to Catholic theology?

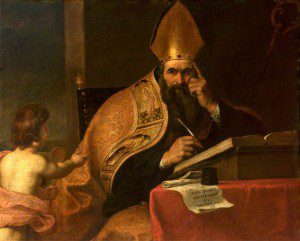

I think it is, or at least would have been to Church Fathers like Augustine. Take, for example, his distinction between use and enjoyment, from his De Doctrina Christiana:

There are some things, then, which are to be enjoyed, others which are to be used, others still which enjoy and use. Those things which are objects of enjoyment make us happy. Those things which are objects of use assist, and (so to speak) support us in our efforts after happiness, so that we can attain the things that make us happy and rest in them. We ourselves, again, who enjoy and use these things, being placed among both kinds of objects, if we set ourselves to enjoy those which we ought to use, are hindered in our course, and sometimes even led away from it; so that, getting entangled in the love of lower gratifications, we lag behind in, or even altogether turn back from, the pursuit of the real and proper objects of enjoyment.

“Use” and “enjoy” have very particular meanings here. Augustine does not mean the former in purely utilitarian terms, nor the latter in hedonistic ones. Ultimately (and to over-simplify), by “enjoy” he means “rest in” or “find fulfillment in”; we use things in order to attain enjoyment, though many objects serve a mixture of functions. Given this understanding, the one “object” we are truly to enjoy should not surprise us:

The true objects of enjoyment, then, are the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, who are at the same time the Trinity, one Being, supreme above all, and common to all who enjoy Him, if He is an object, and not rather the cause of all objects, or indeed even if He is the cause of all. For it is not easy to find a name that will suitably express so great excellence, unless it is better to speak in this way: The Trinity, one God, of whom are all things, through whom are all things, in whom are all things.

We might “enjoy” our neighbors insofar as fellowship is an earthly good in which we rest, but that enjoyment is not full unless we also (and primarily) “use” community with loved ones to grow closer to God. In the City of God, he argues that, without reference to this final end, all “virtues” are actually vices:

For what kind of mistress of the body and the vices can that mind be which is ignorant of the true God, and which, instead of being subject to His authority, is prostituted to the corrupting influences of the most vicious demons? It is for this reason that the virtues which it seems to itself to possess, and by which it restrains the body and the vices that it may obtain and keep what it desires, are rather vices than virtues so long as there is no reference to God in the matter. For although some suppose that virtues which have a reference only to themselves, and are desired only on their own account, are yet true and genuine virtues, the fact is that even then they are inflated with pride, and are therefore to be reckoned vices rather than virtues.

This is a rather cursory overview of Augustine’s point; the truth is a bit more complicated. We might squirm at the idea of “using” our neighbors, or ask why it is that he approvingly cites virtuous Romans earlier in his text, only to later say that they had no virtue at all. But, for now, the topic at hand should take precedence.

If life in the grandest sense is a question of ordering previously-existing goods (and they are goods, since God created them), then is our role as socio-political actors really a question of self-interest? Or, is the real question how we learn to correctly order those goods? To say “self-interest” seems to imply an unchanging set of selfish desires. This is not an idea that Augustine, or Plato before him, could endorse.

What we conceive of as self-interest might really just be how we value particular exterior goods. If I love “freedom,” in some abstract, non-Christian sense, Augustine would likely say “pride” was leading me to mis-order created goods. If I seek fame, vanity; if money, then greed, etc.

So while it might be true that each of us desires what we ourselves desire, that is banal enough. The important question for Christians is why we value what we do and how we re-orient those values toward God. People may have differing personalities; they make express their desires differently, but, ultimately, self-interest is a question of exterior (not interior) goods. We might better spend our time asking not how to make conflicting self-interests harmonize, but rather how to change hearts and minds to see the world as it truly is.