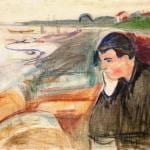

2020’s I Blame Society leans heavily on the “I,” with producer-writer-director-lead actor, Gillian Wallace Horvat in just about every shot. Its basic steps tread those of other found-footage comedy-murder mockumentaries—deep breath—like Man Bites Dog (1992) and Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie Vernon (2006). We meet a psychopathic film director who’s making a movie about the perfect murder—which is, of course, the movie we’re watching—and follow her down a trail of blood. In this case, actually not that much blood (she’s got a thing for poisonings). We rarely catch more than shaky glimpses of half-violent killings from GoPros and stationary camcorders; our protagonist sometimes pauses, stares the viewer in the eye, and cracks a self-aware joke. Every friend she once had (some played by actual friends of the director using their real names, like co-writer Chase Williamson) ends up dead or disgusted. Why slaughter everyone from the homeless to woke film producers? She blames society.

Self-awareness is this movie’s biggest problem. Were I writing a normal review, I would have shot right out the gate with a simple charge: the protagonist is unlikeable and I took no pleasure in watching her goof, gaffe, yuck, or murder. Every second the character is on screen I was praying the whole thing would be a joke, that the film would cut to Andrzej Żuławski’s Possession (1981), or something else easier to watch. I assume some producer or agent told the director cum protagonist this because she takes time out of her busy killing schedule on several occasions to taunt her victims (and here I include the viewer) with the fact that she knows her character isn’t likeable. You see, that’s supposed to make it okay that the character is exceptionally annoying, that we almost never enjoy having her on screen. If we know that she knows that we think her character is film school Steve Urkel, then we are supposed to laugh: “she’s in on the joke, and now I am too.”

It’s clear from the piece that, at some level, the director is the lead character. We get the impression that she has also bummed around the industry and felt hemmed into certain boxes as a female filmmaker (one of the few laughs comes when two dude-bro producers try to “save her career” by telling her she won’t need to come up with any ideas because they have a bunch: “diversity,” “people who you think are white but aren’t,” and the amazing calque, “intersexuality,” which is, I think, intended to be “intersectionality,” though blended with the term “intersex”). It’s tough out there, and all the more for a woman director trying to do big, bold, dark material. But if so, why make the protagonist someone who is clearly unhinged from the start, someone so annoying that from the opening scene it seems like anyone around her feels compelled to flee into the California desert? Why have Gillian the character lure a homeless man into having sex with promises of food and a shower, only to kill him just as they stop bumsen? It’s not just that the character is unlikable—lots of great movies have antihero leads or even annoying ones (paging Pee Wee Herman). The problem is that there’s no vicarious curiosity. I never wanted to see what happened next because I knew precisely what it would be—a murder followed by a joke intended to undercut criticism of the film.

I Blame Society is an onion with nothing at the center—layers and layers of ironic distancing intended to defend a plot we’ve seen before. The whole thing felt like a product of the hyper-ironic culture of the early- and mid-2010s, in which being in on the joke was the joke. “We live in a society,” as the outdated jape goes—ironically of exactly the sort that prefers being conscious of problems to doing anything about them. The issues cited are real enough, and I would love to watch a movie about a female director driven comically insane by a predatory, hypocritical industry. But such a movie would have to commit to itself, to get us to respect the tragicomic figure at its center. I Blame Society is too afraid to say what it means to say—and it’s a worse film for it.