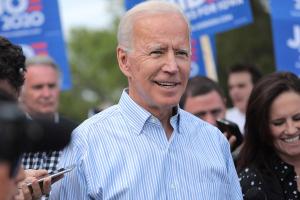

Source: Wikimedia

Outside of the modern United States this would seem a relatively open-and-shut question. Anyone baptized and confirmed Catholic who identifies with the Church and has not been excommunicated is rightly entitled to that label. But, of course, in our deeply polarized society that’s insufficient.

When people raise such an issue, they’re generally asking a political question. They aren’t asking if a public figure like Joe Biden believes in the Real Presence of Jesus Christ in the Eucharist or if he upholds the doctrine of Papal Infallibility. They certainly aren’t asking if he accepts Francis as the true pope or if he donates to the Church and participates in parish life. In fact, it’s not usually just any sort of political question. It’s a very specific one: does the fact that Biden accepts legalized abortion allow him to use the label Catholic?

The seminal importance of abortion for such a definition can be traced back to the so-called “five non-negotiables,” a list of supposedly intractable issues for any Catholic voter. The list (made up almost entirely of issues salient to the early 2000s rendition of the culture war) is clearly no more than a product of its time. This is not to say that there’s no value in it or that its emphasis on the sanctity of human life is bad; quite the opposite—it’s to say that the specific issues it highlights (like say embryonic stem call research and euthanasia) are overly specific and just so happen to align with the politics of the early aughts GOP. The explanation often given is that this is just a coincidence—these issues just happen to deal with life and death (hard to see what same-sex unions have to do with mortality, but nevertheless).

To my mind, many a “social justice” issue (like the Peccata Clamantia) is manifestly about fundamental human life too. But I understand that many disagree. And so I ask: why not concern ourselves with our dropping bombs on countries like Yemen (it’s rather hard to call what’s going on there a “just war” by any stretch)? What about the ethnic cleansing of the Tigrinya happening right now in Ethiopia, violence almost certainly backed by our tax dollars and supported (if only implicitly) by politicians from both major parties? What about support for the execution of the mentally disabled? All of these are issues of human life and death directly affected by the politicians for whom we vote. And yet no one asks if Marco Rubio (who has, at rather convenient times, waffled between a Protestant church and a Catholic one!) gets to call himself Catholic.

I concede, however, that even this might not convince the most dedicated. “Abortion,” they might say, “is the fundamental question. To in any way allow or support it is to call into question all others.” Admittedly, this moves the goal posts a bit from the five non-negotiables (euthanasia, after all, deals with the end of life). But fair enough. The problem is that legal action hasn’t always been the measure of moral action, at least not in Christian history.

Infanticide and abortion were common practices in the Roman and Greek worlds, and with the widescale toleration and eventual institutionalization of Christianity, the Roman Empire did make the former legally punishable (Coleman, Emily, “Infanticide in the Early Middle Ages,” Women in Medieval Society, ed. Susan Mosher Stuard, 57). Indeed, the crime was punishable by death (Ibid.). Though this harsh measure was accompanied by a state-backed economic program to assist poor women and orphans, thereby trying to stem the causes of infanticide (it’s worth noting here that “infanticide” likely refers to exposure more so than what we think of as abortion today, which does complicate things).

This state of affairs was not permanent. So, for example, in hagiographies from early medieval Ireland we find a series of bizarre “abortion miracles,” in which saints disappear fetuses from nuns who have broken their vows [Mistry, Zubin, “The Sexual Shame of the Chaste: ‘Abortion Miracles’ in Early Medieval Saints’ Lives,” Gender History 25:3 (2013), 608]. As confusing as these tales are, however, they are not legal recourses (which is the topic at hand). In medieval Europe, for example, while abortion was, for the most part considered a terrible sin, its legality and consequences were another question. It was only in the 12th century (and even then merely in academic circles) that the old Constantinian model returned:

Jurists who worked during the formative phase of academic (or scholastic) law were quick to agree with Gratian, the author of the oldest canonistic textbook (ca. 1140), that the killing of a human fetus would constitute homicide and warrant identical punitive measures. They also followed another of Gratian’s suggestions to the effect that the humanity of unborn life was not the immediate result of conception but rather occurred subsequently, that is, when embryonic existence acquired limbs and human shape with the infusion of an immortal soul. In prevailing lawyerly opinion, this decisive event came about sometime early during gestation if not, according to the civilian Azo Porticus (fl. 1190), either forty or eighty days into the pregnancy, depending on whether the expected baby was a boy or a girl.

The basic outline of this theory soon enjoyed wide circulation with its insistence on the complete equation of abortion and homicide as long as the slain victim possessed human form. By 1250 it must have been known all across the Latin Christian world, from Portugal and Ireland in the extreme west to Poland and Hungary in the east. Its thoroughgoing dissemination was secured by church officials whose hierarchy adopted the teachings of academic jurisprudence from the outset as its general law. Where lay jurisdictions, on the other hand, were slow to embrace the doctrine (in Germany, for example), or failed altogether to do so (as in England), the rules provided by Gratian, Azo, and their colleagues were nevertheless preached in the ecclesiastical sphere and insisted upon in sermons, private confessions, and courts of spiritual adjudication. (Müller, Wolfgang P., Introduction, The Criminalization of Abortion in the West: Its Origins in Medieval Law, 1-2)

Fascinatingly, medieval people seem to have often treated abortion as a matter of penance (often public) rather than a crime in our modern sense (Ibid., 5f). And, as the above shows, parts of Catholic Europe never quite accepted the legal model.

Does this mean that Richard the Lionheart wasn’t Catholic or that a village hetman or small-time noble who didn’t spend all day lobbying for the absolute criminalization of abortion couldn’t be identified as a Catholic? Given how much of Catholic self-imagination comes from the Middle Ages, this seems a hard sell.

Contrary to what a reader might think, I am no fan of Joe Biden. I think he’s got a checkered record and has been a pretty bad president, all things considered. But it seems obvious to me that he counts as a Catholic, at least until his bishop or the pope decides otherwise. You needn’t like his politics; I sure don’t. But to disagree is not to kick out of the Church, and to fight over politics is not to shatter the Body of Christ.