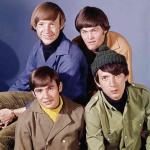

Source: Wikimedia

No better time than another energy crisis to revisit Tamara Jenkins’ Slums of Beverly Hills (1998), the story of young teen girl and her dysfunctional-cum-loving family’s attempt to navigate life in 1976 Los Angeles. Vivian (Natasha Lyonne) and her brothers, Ben (David Krumholtz) and Ricky (Eli Marienthal) are used to getting yelled at in the middle of the night, told to move from one fleabag apartment to the next by their 65-year-old dad Murray (Alan Arkin). They are, as Vivian keeps repeating, “Jewish nomads,” like Abraham and co. if they moved from coral-colored motel to coral-colored motel. Murray sells car parts and has no luck since gas is so expensive, but, by God, he’s got to keep them in Beverley Hills for the schools. He may be a failure as a provider, but he refuses to fail as a father.

And so, he finds his way to a plan. His addict niece, Rita (Marisa Tomei) has escaped from rehab and needs somewhere to stay. Murray’s brother, Mickey (Carl Reiner) has long sent money the family’s way: how much more might he spend if daughter’s taken off his hands? And so at the price of their dad getting guff from his brother, the Abromowitzes move into their first apartment that doesn’t look like a suite in the Bates Motel. Vivian frets over her developing breasts and gets close to a pot dealer named Eliot (Kevin Corrigan) from their last pastel hellhole. Rita tries to get clean and enters nursing assistant school. Murray pursues a dowager of decent wealth and questionable haughtiness. Vivian’s brothers ask her how she can live with those knockers; she shoots back about the older one’s morning wood.

We’re in sitcom territory here. And what’s weird about this movie is how it can take the themes of the Gen-X sitcom and elevate them. Let’s take the father as an example. Throughout the movie he fails his children. He keeps protesting that he’s not old. He has to beg his brother for money (and this ain’t the first time). He calls a Black waiter at Sizzler “Jackson.” He recounts (for the zillionth time, so we gather) a story of past success in which he stabbed an underling with a fork for trying to steal product. At one point he even insists Vivian put a “brassiere” under her halter top (because this new place is fancy!). Toward the end of the film in a moment of abjection and brokenness, he even creeps his hand across the chest of his own niece.

Yet he’s a fundamentally sympathetic character. When he, his kids and his brother’s family get together for dinner, we cheer his eruption at the well-off but self-important Mickey. We see that his kids love him, even though they’ve spent half the movie exhausted with his constant moves and endlessly repeated stories of bygone grandeur. Whatever was (is?) good about the sitcom is here. My dad’s not perfect. Sometimes we can’t even communicate. But I love him nonetheless. QED.

Vivian’s character makes a similar study. She’s unsure of herself and carries much of the comedy of the film, but without ever becoming a caricature or a saccharine excuse for a teenager. So we find her inviting Eliot to feel her up in the apartments building’s laundry room. The setting makes sense—this isn’t some romantic sexual awakening. As we’ve already seen with her father’s brazier requirements and constant negging from her brothers, she doesn’t know what to do with her developing body. Eliot, who is in all likelihood legally liable here (he’s at least 19), is just the boy who happens to be there. Does she love him? Not exactly. But she does like him and is happy to have a man around who isn’t family.

When Rita moves in she introduces her younger cousin to vibrators. It would be easy enough here to give the audience some peep at sexual fulfillment, some scene in which Vivian comes to womanhood by way of orgasm. Instead, she and Rita turn the radio and start singing into it like a microphone, only to be interrupted by Murray. I’ve never been a teenage girl, but that combination of youthful excitement, sexual curiosity, and boundless energy seemed spot on.

Jenkins wrote the movie and keeps a steady hand to guarantee her vision. Slums is really funny. But it’s not just that. It gets the tone of teenage life just right, throwing in that little pinch of absurdity that wakes any dramedy up. Vive la sitcom!