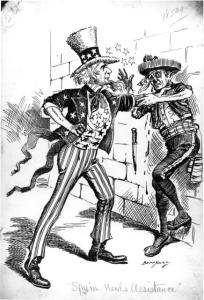

“Spain Needs Assistance” by Clifford Berryman (from the May 5, 1989 edition of the Washington Post).

Source: Public Domain

A disfigured corpse sits in a burnt-out helicopter somewhere in the Kuwaiti desert. The officer responsible for investigating the incident tells his lackey that he better identify the bodies, and, more importantly, better not say this was done by US troops. As the grunt approaches, the corpse reanimates, snaps the guy’s neck, steals his gun, and mows down the officer. Pleased with himself, the soldier-turned-revenant muses: “Don’t be afraid; it’s only friendly fire.”

Uncle Sam (1996) is exactly what you’d expect from this opening scene: a goofy black comedy-slasher with an interest in the Gulf War we’d now consider gauche. A horrifically burned (and deceased) soldier named Sam Harper (David Fralick) ships home to New Jersey to take revenge on the nation that left him to rot. This is a movie where a cop gets impaled with an American flag on the Fourth of July, a film where the killer straps a corrupt congressman to a fireworks display just so the whole town can see him explode in glorious patriotic sacrifice. It’s got a zombified super soldier who steals an Uncle Sam costume from a peeping tom on stilts. You know what you’re getting from the pre-credit sequence. I won’t dispute that. If you don’t like dumb 90s gorefests, don’t check this out.

But there’s something odder going on in this William Lustig-directed and Larry Cohen-written slasher. You might think based on the description above that this is a movie about blowback. The US gets involved in foreign wars, refuses to properly care for its vets, and so they become twisted monsters who hurt and kill themselves and others. Call it the Guy Who Killed Chris Kyle story. That’s not Uncle Sam at all. It’s way weirder than that. In fact, I might call it the most Boomer movie I’ve ever seen.

The main character in Uncle Sam is actually a young boy, Jody Baker (Christopher Ogen), who practically worships his career military uncle, Sam Harper. When his family finds out Sam has finally died, his mother and aunt (Sam’s wife) are clearly relieved. Jody doesn’t notice, and the real arc of the film concerns his slowly coming to understand that his beloved uncle was not an honorable soldier, but a brutal psychopath who physically and sexually abused his sister and his wife. As sober Vietnam vet Jed Crowley (Isaac Hayes) laments toward the end of the movie (and I might be paraphrasing here): “you’re no soldiers; you just love killing.” Crowley provides an honorable contrast to the murderous Sam. He’s clearly traumatized, but he handles it quietly and respectably, disdaining war but still loving service, really just keeping to himself.

His presence and this bizarre backstory undercut any “political” message the movie might initially seem to have. And yet, Cohen writes in all manner of things that sound like critiques of the way the US approaches foreign policy (do I need to remind you of the exploding congressman or the flag-impaled cop?). Sam often spouts lines about getting left to die by an ungrateful country. The poem read over the end credits has a line that may as well be “no war for oil.” But then we see Sam do things like kill delinquents after they desecrate the American flag by burning (wow is that a throwback. Plus, I suspect impaling someone on the stars and stripes is against the flag code, but I’m no expert). He tomahawks Jody’s teacher, a Vietnam draft dodger, who, despite everything else in this film, is played as a reasonable, if somewhat effeminate, guy. We learn he fled to Canada when Jody asks about the war in class. His answer is that it seemed more patriotic to many young people back then to fight against the war than to fight in it. There’s the rub.

Uncle Sam is, for all its goofiness and implied critique (again, a shell-shocked vet dressed as Uncle Sam goes on a killing spree on the Fourth of July), a deeply patriotic movie. It’s the Cold War liberal in cinematic form. There’s a sort of sympathy for those who dodged the draft and those who got sent to die in Nam. There’s a feeling of unease at the misuse of US power to invade foreign countries. There’s even a vague sense that economic interests that are not totally on the up-and-up might be leading the country in directions that aren’t exactly copacetic with most Americans’ desires. But it’s still filled with love for the good ole US of A. Like a previous Lustig/Cohen effort, Maniac Cop (1988), the problem isn’t the system itself, it’s a few bad apples (who, in many cases, were made that way by missteps in the structure—that or just dumb luck). No need to junk the damn thing; it works pretty well. Just a tweak or two will do.

The movie ends with Jody burning all his military stuff—his toy planes, his uncle’s medals, and all the other symbols of his patriotism. He’s got a sad, almost menacing look in his eyes as he glances up at his mom from the burning trash. These final shots struck me as a warning: better mend things now or the youth will lose faith in the whole project! The screen then cracks like broken glass and the credits roll.

As a child of the late-90s and early-00s, I must admit Cohen and Lustig may have been right. My generation’s trust in the US system is at a low ebb. And for good reason! Uncle Sam is an artifact, a testament to how—confusing as it may now seem—people used to feel. Growing up with immense prosperity after a victory in a world war—who can blame them? But we didn’t; I guess we’re all Jody now.