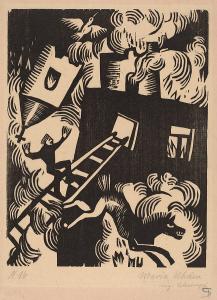

This about sums up April’s life.

Source: Wikimedia.

Now I finally know why all the videos I had to watch in class in the early 2000s looked so bad. On TV, they’d show old-fashioned PSAs about slinging horse and the wonders of man’s newest, greatest mass market innovation—barbiturates—and I’d be amazed at the quality of the image. Sure, they were corny, and everyone looked like the Platonic Form of Kelso from That ’70s Show. But they looked like La Dolce Vita compared to the rad “say no to drugs” skateboarders we got, their washed-out backgrounds complemented by poorly CGI’d squiggles and thunderbolts. ¡Viva la Reefer Madness!

What did I find out? And how?

Well, I watched Peter Hedge’s Pieces of April (2003), of course! The movie isn’t supposed to look like a megalomaniac running 70mm storyboarded every shot; in fact, it was filmed in 16 days for $300,000 on a handheld digital camcorder. Most of it takes place in either a car or a dingy New York apartment building, where actual tenants played extras. Grit is part of the point, like in a scene where our main character, April (Katie Holmes) dresses a Thanksgiving turkey with her new boyfriend, Bobby (Derek Luke). Flat lighting of a bloody raw bird in a half-clean sink really gets the point across. My wife intentionally dry heaved.

But true-to-life grit doesn’t mean it’s easy on the eyes. The real culprit here is early(ish) handheld digital shooting. The camera couldn’t handle wide shots well, so almost everything looks crammed together, which works well-enough thematically for a movie about emotional trauma in tight spaces but doesn’t make for anything above the level of my family’s late-90s home movies otherwise. Is it an accomplishment? Any low-budget film made in under three weeks is. I’m just glad to have my answer, to know why I was always jealous of the movies the Simpson kids got to watch in class. Even if Fluffy Bunny was faking it—so what? The image was crisp.

The story of the picture quality in Pieces of April applies just as well to the rest of the movie, which follows April as she tries (despite many obstacles) to make a Thanksgiving turkey for her estranged family. Her mother (Patricia Clarkson), father (Oliver Platt), snooty sister (Beth), and weed-smoking brother (John Gallagher) take the car from the suburbs to try and reconcile on that holiest of American holidays. Joy, the mom, is dying of breast cancer, which has both made everyone desire reconciliation more and made them blunter about how deeply they dislike each other (or, more specifically how each of them dislikes April and how she feels neglected by them).

From there, the movie writes itself. They learn the value of forgiving April’s vague transgressions (which seem to range from basic petulance to torturing her siblings with matches. Hey, that sounds a little extreme to me, but what do I know. I grew up an only child). She, in turn, proves she’s grown up, is capable of love, and can handle conflict and forgive their emotional distance. It all stays very abstract, which, while it may allow others to slot-in their own experiences, largely just confused me. Aren’t the specifics the point? Did she Guantanamo her siblings or is she just your typical pierced and tattooed dyed-hair suburban daughter gone rogue in the big city? There’s a world of difference between Ted Bundy and a manic pixie dream girl.

A scene at the end in which she’s explaining Thanksgiving to a Chinese family from her apartment building (some of the few people who stop to help her in her quest to cook that damn turkey) captures the essence of the thing. She keeps beginning the story over and over, first by telling the traditional Pilgrims-and-Natives-as-friends version, pivots to Howard Zinn, and finally lands on “we all have to realize we need each other.” We do. That’s true. And it’s not a bad lesson. But it’s also anodyne and not expressed with enough specificity to seem profound. The simplest moral can be given immense power by complex, moving expression. Pieces of April doesn’t go there.

Despite what I’ve written above, I really don’t dislike the movie. It’s heartwarming and makes you feel good. It has a fundamental hope in humanity across racial (her boyfriend Bobby is Black, her saviors are Asian) and class divides that seems entirely foreign now. It even ends with a photo montage of the joyous family reunion in April’s cramped apartment. And that’s the thing really: it all “works,” but in the way critics look for and enjoy during awards’ season. The technical prowess is there. It’s got a good message. The finale shows a commitment to technique. But movies are more than checking boxes. And, while it’s a valiant effort, I fear that’s all Pieces of April does.