Source: Flickr

1998’s The Last Broadcast is a movie made for me. I am a staunch New Jersey supremacist. The film takes place in Jersey’s gorgeously desolate Pine Barrens. I adore true crime and shlocky 90s horror. The Last Broadcast is a (pre-Blair Witch Project) found footage movie about a murder carried out either by the Jersey Devil or a deranged occultist deep in the woods. I love a good mockumentary. This movie is—more than anything else—a serious mockumentary, a strait-laced send-up of TV true crime docs, complete with awkwardly shot expert interviews and dramatizations. And yet, I cannot recommend it. Not as anything more than a historical artifact anyway.

The Last Broadcast is most commonly compared to 1999’s The Blair Witch Project. We have young people going into the woods to investigate some paranormal phenomenon they take seriously only insofar as it might supercharge their own careers. But that’s about where the similarities end. In the more famous film, we see the footage left behind by the murdered filmmakers; in The Last Broadcast we see snippets of this footage, but entirely circumscribed by commentary, interviews, and narration. We’re watching a movie posing as a classic TV documentary, not an indie stitching-together of surreal video held together by nothing more than the tension of the subjects’ journey. The Last Broadcast, in other words, has no real dramatic arc; it doesn’t have much to offer besides continual breadcrumbs that, we are promised, might lead us to see the whole situation differently. But the ending is an awful twist. I’m talking The Village (2004) level stuff. Whatever is good in the movie is undone by the last 10 minutes. Horrible. Tripe. Malevolent. Stupid.

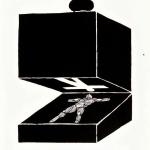

In order to obviate against this deficiency, directors Stefan Avalos and Lance Weiler introduce social commentary. Our narrator and the filmmaker within the film, David Leigh (David Beard) doesn’t just investigate the murder of three public-access TV show makers; he pins the wrongful conviction of the supposed murderer and fourth member of the team, Jim Suerd (James Seward) on the media and their coverage of the trial. Further, he hints that the victims had it coming, at least to some degree. They were, in varying ways, fame obsessed, willing to do whatever it took to become successful in media. They went out into the woods to do a live simulcast on TV, the radio, and the (as yet young) internet, because they needed to be at the center of everything.

I want this to be a critique of a then-unborn social media, of the parasite that is our now universal desire for fame before the eyes of the imagined gormless masses. I want it to be a mirror into our broken souls pitched at the moment just before they were irrevocably shattered (not that all was well before). And that’s there. But it misses the mark. A bit of digging after watching the movie suggested to me why this might be. Weiler has gone on to be named to two World Economic Forum steering committees—one on the future of “content creation” and the other on digital policy. Avalos has gone on to deal with A.I. in cinema. The Last Broadcast certainly presages their interest in tech (it was the first movie shot, edited, and screened via purely digital means at Cannes). I haven’t seen their other work; it might be phenomenal. But it’s difficult for me not to discern in the movie’s missteps the directors’ futures.

The biggest proponents of A.I. apocalypticism are, after all, tech billionaires like Peter Thiel and Elon Musk. Tech CEOs build isolated bunkers they imagine will protect them from the climate catastrophe they themselves have had a major hand in. They proscribe the use of tablets and other digital hardware by their own children, even as they push them on the world. It’s not that their warnings are wrong: A.I. is terrifying, kids do spend too much time online (we all do). But there’s a blindness to these opinions, an inability to reckon with the system in which tech leaders participate. The Last Broadcast seems to lose its way in about the same place. It promises scares but delivers a documentary. It swears by true crime and yet turns to the outlandish by the end. It criticizes our obsession with fame and position while leveraging its own particularities to just that end. Put otherwise, it just doesn’t—can’t—deliver.