Father Peter Whelan is best remembered for two things in South Georgia:

Father Peter Whelan is best remembered for two things in South Georgia:

1. He served the spiritual needs of Confederate Irish soldiers at Fort Pulaski near Savannah, was captured, and became a Union prisoner of war in New York for six months. He refused to leave captivity until all the solders were exchanged.

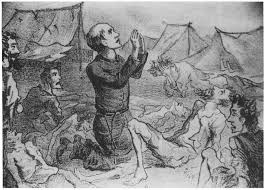

2. He served as chaplain at Camp Sumter near Andersonville, Georgia (now Andersonville Prison) where many Catholic Union solders were kept. Conditions were appalling and deadly. He became known by soldiers as the Angel of Andersonville or the Good Samaritan of Andersonville.

This Saturday will be the 150th anniversary of Father Whelan’s departure from this earth. To mark this significant anniversary, there will be a commemoration at the Catholic Cemetery of Savannah where he is buried. Below I share a brief summary of his life prepared by the Diocesan Archives of the Diocese of Savannah.

Peter Whelan responded to an appeal for priests from American Bishop John England. He came to the United States and was ordained in 1830 for the Diocese of Charleston. During the first two years of his priesthood, he served as Bishop England’s secretary. Between 1832 and 1837, Fr. Peter Whelan ministered to Catholics in the Diocese’s rural territory in North Carolina.

In 1837, Fr. Peter Whelan was named pastor to the Church of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary located in Locust Grove, GA. This is the oldest continually worshipping Catholic community in the state of Georgia. Fr. Peter served Catholics in the rural areas around Locust Grove in both Georgia and South Carolina for nineteen years. He was ministering in Locust Grove when the Diocese of Savannah was formed, comprising the full state of Georgia and East Florida, and incardinating him in the process.

In 1857 he was appointed Vicar General of Savannah. He was serving as temporary Diocesan Administrator when Bishop Barry died en route to France (1859). The American Civil War caused the Pope trouble finding a new Bishop, so Fr. Peter continued to Administer of the empty See until 1861. Finally the Diocese of Savannah was assigned to Bishop Augustin Verot, Administrator of the Apostolic Vicariate of Florida. While in Savannah, Fr. Peter traveled out to Fort Pulaski on Cockspur Island. There he celebrated mass almost weekly for the Montgomery Guard, an Irish unit made up of mostly Catholic men. In February in 1862, Bishop Verot recorded in his Episcopal Acts that Fr. Peter was absent from the Clergy Retreat, being “virtually a prisoner at Fort Pulaski.” He experienced the 30-hour bombardment of Fort Pulaski on April 10th and 11th by Union Troops. After Colonel Charles H. Olmstead surrendered, he accompanied the men as a prisoner of war and was transported to Governors Island, NY. Fr. Peter petitioned to serve as a chaplain to the men, and celebrated mass almost daily. He requested food and clothing donations from priests in the Archdiocese of New York and the Sisters of Charity in Baltimore. When Fr. Peter was paroled at the request of Archdiocese of New York’s Vicar General, Rev. William Quinn and its clergy, he refused to leave his men, staying out the six-month capture.

After Fr. Peter Whelan was exchanged with other prisoners of war, he returned to Savannah and resumed his position as Vicar General of the Diocese. In addition to his duties at the Cathedral, Bishop Verot also assigned Fr. Peter the task of overseeing all spiritual needs of Confederate Military posts in Georgia. When Fr. William Hamilton discovered Camp Sumter, Andersonville in 1864, it was part of Fr. Peter’s responsibility to organize its ministry. Fr. Peter went himself and preserved the longest of the five priests who offered spiritual aid to the Union soldiers. He arrived June and did not leave until October of 1864. Camp conditions were terrible. Fr. Peter would wake up every morning in his small shack about a mile from the camp, eat breakfast, say his prayers, and walk to the prison. He served all the detainees from 9 am to 4 or 5 pm, walking back in the evening. Diaries record his daily presence, offering confession, administering last rites, and encouraging the distressed with kind words. He would sometimes crawl across the camp on his hands and knees so that he could hear the last whispered confessions of a prisoner taking cover out of the sun under in a shallowly dug hole. He brought in what provisions he could find to feed and clothe the men. He also petitioned for the lives of six raiders, part of a large gang terrorizing the camp, who stole from captives, sometimes killing men in the process. When his request for clemency was denied, Fr. Peter blessed the condemned before they were executed. His health was weakened by a lung ailment, picked up at the camp.

Though he left for Savannah in October, he arranged to get what provisions he could sent to Andersonville. Fr. Peter lived out the rest of the war in the city of Savannah. He resumed his role as Diocesan Vicar General when he returned, but did not forget about the men in Andersonville. He arranged for flour to be sent to Camp Sumter. It was made into bread and distributed to the remaining prisoners. Some called it “Peter Whelan’s Bread,” and credit it for keeping them alive during the rest of their captivity.

Fr Peter testified in the US House of Representatives during the Trial of Confederate Captain Henry Wirz, commander of Camp Sumter in Andersonville, GA. He carried on correspondence with Edwin Stanton, Secretary of War petitioning him for reimbursement for the flour used to feed Camp Sumter’s prisoners and complaining about the state the Cathedral Cemetery in Savannah. It had been incorporated into the Union’s defensive earthworks, disinterring its residents in the process. While Fr. Peter did not receive a favorable reply to the former, the War Department did agree to clean up the cemetery. Fr. Peter went on to be named pastor of St. Patrick’s Church in Savannah and served there for a couple of years before retiring from illness to the Cathedral. He died on February 6, 1871 and his funeral procession is remembered as the largest in Savannah for one hundred years.

Nicknamed, “the Angel of Andersonville,” Fr. Peter Whelan has been well remembered by Savannah natives and Civil War historians since his death.