In early 2024, I visited Saint Paul Catholic Church in Ellicott City, Maryland, an old mill town a few miles west from Baltimore. The town had been terribly devastated a few years prior by flash floods. A welcoming secretary opened the parish church, which stood atop a hill overlooking the busy main road. A plaque inside the church noted that in that place in 1914, the baseball legend Babe Ruth married Helen Woodford. I asked the secretary if she was aware that the third bishop of Savannah and first bishop of Saint Augustine, Florida had been the pastor from 1853 to 1858. She had never heard of this, even though, she confided, she had been born and raised in Ellicott City, and had always been a parishioner of Saint Paul. No plaque recalled the ministry of Father Augustin Vérot who arrived to the United States in 1830 from France as a missionary of the Society of Priests of Saint Sulpice, or Sulpicians as they are commonly called. In 1861, Pope Pius IX appointed him Bishop of Savannah while already holding the office of Vicar Apostolic of Florida.

In 1865, right at the conclusion of the Civil War, Bishop Vérot approached the Sisters of Saint Joseph of his native town of Le Puy, France and invited them to work in the war-ravaged South by educating children and staffing an orphanage in Savannah. Vérot had a deep desire to reach the poorest in society, and as Rev J. J. O’Connell recorded in 1879, Vérot “wished to see God better known and more faithfully served.” Bishop Vérot was dedicated to his flock in Georgia, and the harsh conditions did not keep him from ministering to it. In this great spirit of faith and missionary work, he invited the Sisters to educate the least fortunate of his diocese, black children of the newly enfranchised blacks, despite the opposition faced by Southern society. The Sisters first arrived in Saint Augustine, and by 1867 enough sisters had arrived in Saint Augustine that Vérot opened a school in Savannah for the Sisters to staff. They also ran an orphanage located in the Scarborough House in Savannah.

By 1869 the Sisters’ work was noted in the Savannah Republican when the local newspaper reported that “the Sisters of St Joseph are now teaching one hundred colored children. They are quietly and unostentatiously accomplishing an immense amount of good amongst the colored people of this city.” Unfortunately, their work was not appreciated by all in Savannah. Some Catholics and non-Catholics alike, referred to the Sisters using derogatory names. The Sisters ended their apostolate to black children due to financial constraints and decided to concentrate on the orphanage, which by the end of 1871 had been named Saint Joseph’s Barry Male Orphanage. Vérot’s efforts and willingness to serve others provided much needed support to educate black children and orphans in the Diocese of Savannah. The ministry of the Sisters was continued by Benedictines who opened Saint Benedict the Moor Parish in 1874, by members of the Society of African Missions, and much later, the Missionary Franciscan Sisters of the Immaculate Conception.

One of Vérot’s greatest achievements came through his many complaints levied against the City of Savannah in regards to the public school system. He argued that public schools were teaching the Protestant faith to Catholic children through religion lessons and the readings of the Bible. After years of negotiations, the City of Savannah agreed to provide public funds to operate the city’s Catholic schools. The arrangement lasted over forty years, until 1917. This included both schools for black and white children.

In 1870, Bishop Vérot was named the first bishop of Saint Augustine, and was relieved of his responsibilities in Georgia. Some argue this was the result of his many lively interventions during the First Vatican Council in Rome (1869-1870), which did not follow the expected decorum of an ecumenical council. Dubbed “the terrible child,” writings of that time state the bishops would audibly moan every time Bishop Vérot rose to address them. Most notably, he opposed along with other prelates from the United States the approved document on Papal Infallibility.

Bishop Vérot led the 8,000 faithful Catholics in the Diocese of Savannah in the 1860s with great hope for a brighter future where Christ would be better known and loved. Through war, social upheaval and uncertainty, the faithful gathered with tremendous faith, and every one of us today is an heir to their heroic perseverance. As we celebrate 175 years since the foundation of our diocese, we look forward to how it is that we today are writing the history of tomorrow for future generations of Catholics to come.

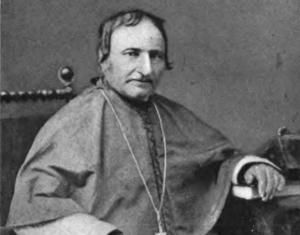

Picture taken from Wikipedia. Picture in Public Domain because it was published before 1923.