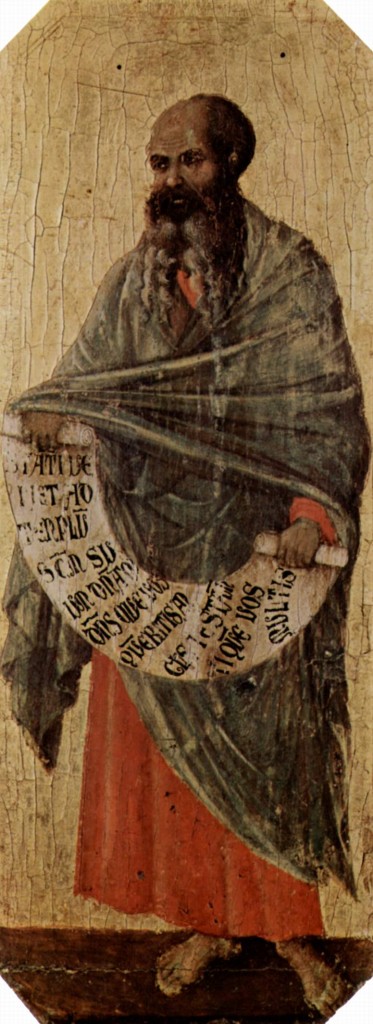

Isaiah 65:17-25 and/or Malachi 4:1-2a

What It’s About: Both of these prophetic texts offer visions of the future. Both offer hope to people who have been trodden down and persecuted. Out of the midst of all that suffering, these passages suggest, will come a great setting-right of the world. They differ sharply in how this will happen; Isaiah emphasizes that the downtrodden will be pulled up into dignity and restored to their rightful place, while Malachi emphasizes the poor fate of the wicked oppressor. But in both cases the effect is the same; the prophets are signaling that the current age of suffering will not go on forever.

What It’s Really About: Both of these texts share a broad context: the aftermath of the Babylonian invasion and destruction. This part of Isaiah probably dates to the period of reconstruction in Judah after the return from Babylonian exile, when the temple was perhaps being rebuilt. Malachi probably dates to just a bit after that, although dating Malachi is a little tricky. In both cases, though, there is a pervasive sense of hopefulness. Third Isaiah (chapters 56-66) and Malachi share a focus on God’s restoration of all that has been lost to war and the chaos that followed. In particular, this passage from Isaiah focuses on the very human experiences of birth, death, hopefulness, building a house, eating food, and all the things that comprise everyday life. By pointing to a vision of normalcy, Isaiah is saying in a powerful way that God is about to restore the old happy ways, but better, so that life is long and beautiful and death is not always hovering nearby.

What It’s Not About: The business of theologizing suffering is a tricky one, and in these texts that deal with the restoration of lost peace and life, there is little said about why those things were lost in the first place. But the prophetic tradition, of course, has a keen understanding of why destruction was visited upon Judah in the form of the Babylonian armies: it was because God allowed it to happen, even caused it to happen, because of the wickedness of the people. The Babylonian invasion and exile were ultimately, in the eyes of the prophets, divine acts. These hopeful passages then have to be tempered with the realization that there is something now between God and the people–a history of violence and destruction that had not been there before. There can be no innocent relationship anymore, like there might have been with Abraham or Moses, because the parties to the relationship (God and the people) have abandoned each other only to return to each other. Like a marriage that has broken up and then reunited, this rupture will leave marks. That’s not in direct view in these passages, but it’s always there in the background.

Maybe You Should Think About: I’m preaching this Isaiah text this week, along with the Luke passage below, in the context of the US elections, which will have just concluded the Tuesday before. This is a text that speaks to a period of tranquility and detente after a time of turmoil, fear, and anger, and that seems to me to be a very suitable text for this moment in our collective life together. My congregation is probably 85% of one political persuasion and 15% of another, but even in a community as homogenous as that, there is woundedness and pain from this long and brutal election cycle. Isaiah’s words have something to say to us as we begin to stitch back together the fabric of our common life.

What It’s About: A majority (but not all) of scholars agree that Paul didn’t write this; let’s get that out of the way. This is probably written by someone in Paul’s name, which sounds really fishy to us but which was totally normal in antiquity. Someone wrote this hoping to capitalize on Paul’s reputation to get this read, and also to continue speaking in the way they thought Paul would have spoken were he still alive.

For me, that helps to make sense of this passage. Because this passage is a long way from early Paul, where commensurate community and sharing were chief virtues. Paul himself had a high value on community that shared resources and protected those who had little or nothing; see, for example, his discourse in 1 Corinthians 11. But here, the author of 2 Thessalonians says something that it’s hard to imagine the authentic Paul saying: “Anyone unwilling to work should not eat.” This is at odds with Paul’s own words elsewhere, but also with the egalitarian and communitarian ethos presented in the book of Acts, for example, and evidence throughout the material record of early Christianity. This sentiment, that you should work for your food and not expect the community to provide it, cannot belong to the earliest Christian communities, but probably represents a later instantiation of the community, perhaps a couple of generations into the tradition, when people had begun to take advantage of Christian community.

What It’s Really About: Earliest Christianity, if we are to believe the texts of the New Testament, was in some times and places a kind of social experiment. Christians seem to have tried to organize their communities around sharing–see Acts 4:34-35, for example. This seems to have been the value that Paul had in mind in 1 Corinthians 11. But this communal way of life seems to have lasted only a generation or so, and here in 2 Thessalonians we see a strikingly different attitude: work for your own food. While this is an attractive principle for those who have the means to do so, it is an abandonment of that early Christian ethos of sharing resources.

What It’s Not About: Idleness is the guiding principle of this passage, and it’s hard to escape the realization that idleness is a vice that is mostly missing from the gospels. If idleness is a vice, then industriousness is the corresponding virtue, and not very often do you find Jesus propounding on the virtue of industry. (There are some texts that you could interpret that way, but that’s hardly the core of his message). To the contrary, Jesus is always visiting, speaking with, helping, and praising the sorts of people who cannot or do not work for their own food: the sick, the possessed, the dispossessed, and the marginal. This angers a lot of people that Jesus meets along the way, of course, but it’s hard to imagine that Jesus would have said anything like what this passage from 2 Thessalonians says. Idleness is not a vice for Jesus; idleness is a sign that somewhere the social fabric has frayed, and that the person needs to be woven back in again.

Maybe You Should Think About: Why does the Christian church exist today? There are probably lots of reasons: community, charity, worship, education. But our first instinct is usually not to think of church as a kind of safety net, which is what it was for the earliest Christians. This was one of the powerful things about Christianity for the earliest Christians: it provided a floor below which you would not fall. There would always be something to eat, no matter how poor you got. There would always be someone to take care of you, no matter how sick you got. There would be someone to look after your children if you died. Part of the lure of Christianity was social; it gave city-dwellers (and early Christians were overwhelmingly city-dwellers) a network to rely upon when they were far away from family and home. We have largely lost that impulse today; churches do that kind of work, but it’s often (usually) external instead of internal. It seems that the author of 2 Thessalonians had lost it too. But what would it look like for us to think about reclaiming that model of interdependent community for church today? What would it look like to think of church as a safety net for its members and others in its network–not as an ancillary part of the church’s mission, but as a core part of its identity?

What It’s About: This is the counterpart to the Isaiah and Malachi texts above. In those texts, the temple was being rebuilt; here, it’s at the height of its glory. In those texts, the “the days will come” is a hopeful thing, looking to a time when things will be set right. Here, the “the days will come” is frightening, a glimpse at a time when things will fall apart again. Where Isaiah and Malachi looked ahead hopefully, Luke has Jesus looking ahead in trepidation. But Jesus doesn’t see these tumultuous times as all bad; they are a time when people will be able to exercise their faithfulness and earn salvation by their endurance.

What It’s Really About: Luke, along with Matthew, was probably written by and for the second generation of Christians, somewhere in the range of the year 80. While it describes events in the 20s or 30s, then, Luke is in a context of later Christianity, when the nascent faith has come into conflict with various outsiders and has begun to suffer persecution. This passage makes sense in that context; in Luke’s world, Christians were experiencing wars, insurrections, and arrest. So Luke’s gospel remembers Jesus’ words about that eventuality, and passes them along as a comfort and a strength to those who were undergoing trials.

What It’s Not About: Curiously, this isn’t a call to arms or resistance. It’s not a warning of coming turmoil, given so that believers can arm themselves. To the contrary, it says that you shouldn’t even think of a defense of yourself. God will give you the words; just be who you are, suffer the betrayals and violence, and rest in the knowledge that Jesus saw this coming. This is an interesting contrast to the culture-warrior mentality of many Christians today, me included, who see it as a Christian duty to oppose oppression and stand up for Christian values. But Jesus here seems to be advocating a less militant, and more trusting, approach to the world.

Maybe You Should Think About: As I said above, I’m preaching this text and the Isaiah one above on the Sunday after election day in the US. Together, I think they provide us with material to think about what comes next after a national crisis–and that’s what this election is turning out to be. The election has divided America and Americans, causing rifts between friends, family, and churches, and leaving scars that will linger for years. None of this is strange to Isaiah or Luke, though; they lived in times when much worse happened. These passages will help us to speak to people who (hopefully) will have begun the process of turning toward the future and leaving this ugly season behind us.