RJ Snell’s Acedia is about acedia. But before he gets to his extended analysis of that vice, he offers a superb, brilliantly brief, ontology and anthropology, drawing on the resources of Trinitarian theology and the book of Genesis.

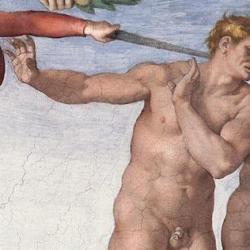

Among other things, Snell emphasizes the gift that is human work, a gift first given to an unfallen Adam in what is known in Reformed circles as the “dominion mandate.” (In a footnote [38, fn 9], and rightly criticizes the Reformed treatment of this topic for its insufficient attention to “the church, sacraments, salvation.”) Snell observes that Christians sometimes view the mandate “as supporting a ‘cultural of exploitation,’” but makes it clear that this is not the thrust of the command to Adam: “if the mandate reflects the character of God, and God is fundamentally self-communicative love, then the mandate to subdue the world would best be read as a vocation of self-donation, even if suggesting human mastery.” Work is transitive, and thus affects the objective world, but, citing John Paul II’s Laborem Exercens, Snell argues that “the subject of work is the human, and the mandate of dominion is as much about the human who ‘manifests himself and confirms himself as one who dominates’” (28). Labor is not necessarily self-alienating; the creation design is that we find ourselves in our labor.

Human dominion isn’t exploitation when it is carried out according to “a thing’s own ‘rhythm and . . . logic’” (42, citing Ratzinger). Snell adds, “work which violates the proportionality and integrity of a thing, according to a thing’s own act of existence, deforms it” (42). We are to work with things “without in any way violating their inner logic” (45, emphasis added). He cites Romano Guardini’s wonderful illustration of sailing a boat: “Those who control this ship are still very closely related to the wind and the waves. They are breast-to-breast with their force. . . . We have here real culture – elevation above nature, yet decisive nearness to it” (43).

Which I may or may not agree with. No doubt, “intelligent use improves the soil” (49); undergrazing can be as damaging as overgrazing. Most of the challenging questions, though, aren’t of the Wendell Berryish variety: Is it proportionate to the integrity of silicon to turn it into micro-chips? It is part of the inner logic of metals and other materials for us to construct them into airplanes or skyscrapers? Am I decisively near to nature when I’m reading Snell’s book in order to write a blog post on my computer? I don’t feel near to nature; but does that mean I’m not engaged in cultural activity? Without more specific guidance, it’s hard to know what deforms and what doesn’t, what counts as genuine culture and what is . . . something else.

In any case, Snell makes it clear that “there is no indication that God intended humans to keep the garden in its original condition without effecting any change whatsoever; like a servant charged to meticulously maintain the owner’s vision. . . . Rather than rejecting the results of human work and culture, God seems to welcome them, now transformed and redeemed, into his vision of final righteousness and peace” (38-9; Snell cites Isaiah 60).

One of Snell’s tests of good work is to ask whether it can “fill the temple”: “Is this the sort of work I could present to God and God’s people as a ‘house warming’ gift which would adorn the halls of the temple forever?” (52). A great question. It’s the final question of all human labor.