At the beginning of their Dialectic of Enlightenment, Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno define Enlightenment in terms of disenchantment of the world: “Enlightenment’s program was the disenchantment of the world. It wanted to dispel myths, to overthrow fantasy with knowledge. Bacon, ‘the father of experimental philosophy,’ brought these motifs together. He despised the exponents of tradition, who substituted belief for knowledge and were as unwilling to doubt as they were reckless in supplying answers. All this, he said, stood in the way of ‘the happy match between the mind of man and the nature of things,’ with the result that humanity was unable to use its knowledge for the betterment of its condition” (1).

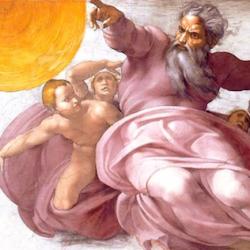

To accomplish this disenchantment, Enlightenment strives to overcome anthropomorphism, “the projection of subjective properties onto nature,” which it regards as “basis of myth.” As the authors explain the Enlightenment view, “The supernatural, spirits and demons, are taken to be reflections of human beings who allow themselves to be frightened by natural phenomena. According to enlightened thinking, the multiplicity of mythical figures can be reduced to a single common denominator, the subject. Oedipus’s answer to the riddle of the Sphinx – ‘That being is man’—is repeated indiscriminately as enlightenment’s stereotyped message, whether in response to a piece of objective meaning, a schematic order, a fear of evil powers, or a hope of salvation” (4).

It’s not an accident that so many counter-Enlightenment thinkers write tales of talking beavers, elves, and hobbits. The very existence of Peter Rabbit is a protest to the reductionist mechanization of nature.