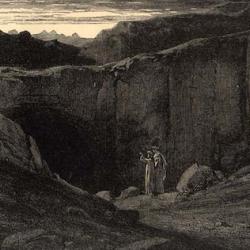

In the course of a review of Vittorio Montemaggi’s Reading Dante’s Commedia as Theology, Rowan Williams offers these observations on Inferno and Purgatorio:

“There is still a tendency among not very attentive readers – not to mention people who have read almost nothing of the work but have picked up the odd juicy morsel – to think of the Inferno as the really ‘interesting’ section of the poem, the part where recognizable human emotion is most dramatically depicted and evoked: guilty love, transgression, punishment, tragic disaster and horror.”

Needless to say, that’s not Dante’s intention: “Hell is where the damned stay, immobilized by their choices; and for just that reason it cannot be where the poem stays. . . . What opens up for him and his readers is finally a sort of global vision of what sin is, the immobilizing of all human action and speech. There is nowhere to go from this point, unless the imagination can be revived. The state of mind of the Inferno is one in which there is no way of telling one’s story that does not lead back to the same place, the fixity, the frozenness that one has at some level chosen.”

Residents of Purgatory aren’t lesser sinners than those in Hell. They are, rather, sinners who have been unfrozen, and so made capable of telling their stories differently: “they know what to say about themselves, how to imagine themselves precisely as sinners, that is as agents who have chosen what is empty and meaningless yet have recovered the words to name their condition and so to imagine their hope.” Dante “configures human freedom in speech and action as the distinguishing feature of the life of creative penitence. The souls in Purgatory have received the gift of seeing things truthfully and acting on what they see – including seeing themselves.”

In short, “they begin to see themselves as truly persons, who can be activated by grace to grow in freedom towards God’s purpose for them.”