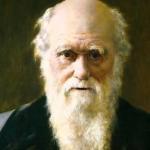

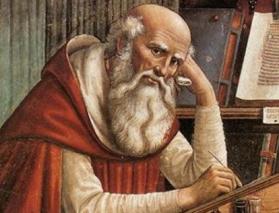

In his book on sacral Kingship (90-1), Francis Oakley points to the disjunction between Augustine himself and the medieval writers to claimed his mantle. Augustine’s political theology in the City of God has been read through the lends of his anti-Donatist writings. A more theocratic Augustine results:

“the Augustine whom one usually encounters in the Latin Middle Ages is the Augustine of the City of God only insofar as that work was reinterpreted in light of the tracts he wrote during the course of his long and bitter struggle against the Donatist heretics in North Africa. In those tracts, written, as it were, in the stress of battle, he was led to assert the principle that Christian rulers were bound to use their power to punish and coerce those whom the ecclesiastical authorities condemned as heterodox. By so doing, he was necessarily according a somewhat loftier dignity, higher authority, and more far-reaching responsibility to Christian rulers than to pagan. As a result, medieval authors who did not fully share his sombre doctrine of grace, who rejected his sternly predestinarian division between the reprobate and the elect, and who saw instead in every member of the visible church a person already touched by grace and potentially capable of citizenship in the City of God (the transtemporal and transpatial congregation of the blessed), broke down the firm distinction between the City of God and the Christian societies of this world that Augustine had drawn so firmly in all but a handful of texts in the City of God itself. As a result, they understood him to be asserting that it is the glorious destiny of Christian society – church, empire, Christian common- wealth, call it what you will – to work to inaugurate the Kingdom of God and the reign of true justice in this world.”

Augustine had been an opponent of the Christianized sacral kingship articulated by Eusebius, but “by one of those superb ironies in which the history of ideas abounds, the name and prestige of Augustine became one of the instrumentalities whereby archaic notions of sacral kingship, to all intents and purposes excluded by the New Testament vision of politics, were nevertheless able to survive in Latin Christendom, just as, in the form of the Eusebian vision, they had been able to survive in the Byzantine east.”