From the earliest times, Christians have offered typological interpretations of ancient myths. According to Marie Cabaud Meaney (Simone Weil’s Apologetic Use of Literature), Weil revives this tradition in a new intellectual milieu:

“Weil uses Christology as the hermeneutic key to these mythological texts at a time when people such as Durkheim had reduced religion to a sociological phenomenon, when Bultmann was demythologizing the Gospels, and after Higher Criticism had been looking at the Bible through a positivistic lens since the previous century. Weil, on the contrary, chooses a method opposed in every way to these trends, for she not only denies a mythological character to the Gospel, she even reads myth from a Christian perspective. . . . Myth does not mean for her ‘human fiction’ or ‘lie,’ which should be eliminated in order to discover the ‘historical Jesus.’ Rather, myth is already an epiphany of Christ taking place before his historical incarnation, or may even be the sign of other incarnations. Weil’s approach is at the polar opposite of positivism: rather than reducing reality to the empirical data gathered through sense perception, she sees the sacred in the form of the Logos present everywhere” (18).

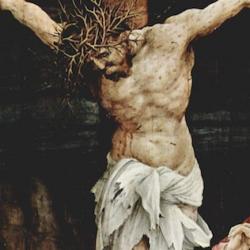

It’s not always convincing. Weil claims Prometheus as a Christ figure whose suffering is a Passion for the sake of human beings. In one sense, it’s an obvious move: “Prometheus seems to be the most Christlike figure in Greek mythology: he loved human beings to the extent that he saved them from extinction by bringing them fire against the explicit orders of Zeus, and was consequently nailed to a high rock in the Caucasus. Thus the nature of his suffering (crucifixion) and its cause (his love for humanity) are similar to Christ’s” (144).

To make this work, though, she has to deny the obvious – that Prometheus suffers for his own wrong, and that Zeus and Prometheus are at odds. Weil bites the bullet: “Prometheus accepted this suffering freely. He knew what was awaiting him, yet decided to ensure the survival of the human race by his gift of fire. In Weil’s eyes, he experiences an abandonment similar to that of Christ on the cross. In reality his disagreement with Zeus is merely apparent. Neither he nor Zeus really hate each other. Freely the one accepts suffering, and freely the other bestows it—a surprising idea, given Prometheus’ angry words when talking about Zeus” (144-5).