“All that exists consists of force and matter,” says atheistic materialism.

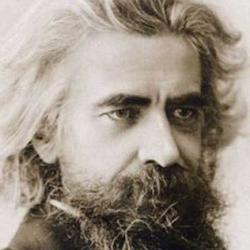

Very well, replies Vladimir Solovyev (Lectures on Godmanhood, 81-2). Let’s assume that is true and see where it leads.

“Force” and “matter,” he points out, are :very general conceptions”: “We speak of physical forces, we speak of spiritual forces. Forces of either kind can be real. In agreeing with materialism further, that forces cannot exist by themselves, but necessarily belong to certain real units or atoms, which represent the subjects of these forces, we can understand with Democritus the subject of these forces — the human soul – also has to be such a real unit, a special atom or monad of a higher order which possesses, as all atoms do, eternity.”

Reductionists claim that these spiritual forces are merely excretions of physical processes (can you say David Dennett?): “soul, or thought, is an emanation of the brain just as bile is the secretion of the liver.” They are “poor scientists and poor philosophers.”

But if we are open to reality as it is, then “there is no basis for denying the existence and independence of spiritual forces known to us.” We have no logical reason to deny “the full reality of the infinite multitude of other forces, unknown to us, occult for us in our present state.”

Thus, given the generality of the claim that “all that exists consists of force and matter” doesn’t “exclude anything and can be acknowledged even from the spiritual point of view.”

Similarly with the claim that “all that occurs occurs of necessity, or according to immutable laws.” Nothing in that claim logically excludes the possibility of a necessity that is compatible with freedom: “it is necessary for God to love all and to manifest the eternal idea of the good in creation; God cannot nourish enmity, in God there can be no hatred; love, reason, freedom, are necessity with God.” In short, “for God freedom is necessary.”

If the materialist rejects that possibility, it is because he has excluded it from the outside, defining “necessity” in a way that, by definition, makes freedom impossible.

Solovyev concludes that “the fundamental propositions of materialism, which are undoubtedly true, by their generality and indefiniteness do not exclude anything and leave all options open” (83).