Typology was a traditional method of reading Scripture, one that persisted into the Victorian age. Most obviously, this took the traditional form of finding shadowy figures of Christ in Old Testament characters and institutions and promises.

J.C. Ryle, a leading Evangelical Anglican, claimed that one “golden chain” runs through the whole of Scripture – it is entirely about Christ: “no salvation excepting by Jesus Christ. The bruising of the serpent’s head, foretold in the days of the fall, – the clothing of our first parents with skins, – the sacrifices of Noah, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, – the Passover and all the particulars of the Jewish law, -the high-priest, -the altar, -the daily offering of the lamb, -the holy of holies entered only by blood, – the scapegoat . . . all preach with one voice, salvation only by Jesus Christ” (quoted in Landow, Victorian Types, Victorian Shadows, 32-33).

John Henry Newman, who famously converted to Roman Catholicism after lead the “Tractarian” or “Oxford” movement within the Church of England, had an Evangelical background and his training in Scripture, as well as Evangelical fervor, stayed with him through his various conversions. In one of his sermons, he explained how Moses served as a type of Christ. Deliverance from Egyptian slavery clearly “prefigures to us the condition of the Christian Church! We are by nature in a strange country; God was our first Father, and His Presence our dwelling-place? But we were case out of Paradise for sinning, and are in a dreary land, a valley of darkness and the shadows of death. We are born in this spiritual Egypt, the land of strangers . . . and by nature slaves we are, slaves to the Devil. He is our hard task-master, as Pharaoh oppressed the Israelites” (quoted in Landow, 23-24).

For Henry Melvill, a Church of England priest and head of the East India Company at one time, taught and preached typological reading. This provided an explanation, he said, for why certain episodes were included in the Bible in the first place: “We are not to regard the Scriptural histories as mere registers of facts, such as are commonly the histories of eminent men: they are rather selections of facts, suitableness for purposes of instruction having regulated the choice. . . . Perhaps more frequently than is commonly thought, it is because the fact has a typical character that it is selected for insertion: it prefigures, or symbolically represents, something connected with the Scheme of Redemption, and on this account has found space in the sacred volume” (quoted in Landow, 38).

One of the masterpieces of this period, Patrick Fairbairn’s Typology in Scripture, first published in 1845, remains in print to this day.

Typology wasn’t simply a general hermeneutical system. Certain readings of passages became standard. The animal skins given to Adam and Eve outside the garden were seen as types of the righteousness of Christ.

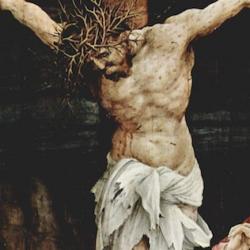

Moses striking the rock had a variety of uses. It was often taken as a type of the historical event of the cross. Henry Melvill wrote of this passage: “It is generally allowed that this rock in Horeb was typical of Christ; and that the circumstances of the rock yielding no water, until smitten by the rod of Moses, represented the important truth, that the Mediator must receive the blows of the law, before He could be the source of salvation to a parched and perishing world” (quoted in Landlow, 67).

Charles Spurgeon applied the typology personally to the experience of individual believers. Each convert is like one of the Isarelites in the wilderness, looking to the Rock that is Jesus to provide refreshment in a dry and arid land: “O! blessed Jesus, thou art indeed a sweet antitype of the rock. Once my thirsty soul clamoured for something to satisfy its wants; I hungered and I thirsted for righteousness; I looked to the heavens, but they were as brass, for an angry God seemed to be frowning on me; I looked to the earth, but it was as arid sand, and my good works failed me. . . . But well I remember when my thirsty soul fainted within me, and God said, ‘Come, hither, sinner, I will show thee where thou mayest drink,’ and he showed my Christ on his cross, with his side pierced and his hands nailed. . . . You see, then, beloved, that this rock is a type of Christ personally, it is type of him dying, smitten for our sins” (quoted Landow, 69-70).

This personalized typology took hymnic form in William William’s “Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah”: “Open now the crystal Fountain, / Whence the healing streams do flow; / Let the fiery cloudy pillar / Lead me all my journey through.”

More innovatively, some Victorians transformed the scene into a type of the softening of a stony heart, whether the heart was softened by conversion or by some other event of life. In the sixth book of Wordsworth’s The Excursion (1814), Ellen tells her mother that God has given grace to help her bear the pain of lover’s betrayal. It’s an example of typology being put to “secular” use, as an image of a lover’s recovery from romantic depression:

There was a stony region in my heart;

But He, at whose command the parched rock

Was smitten, and poured forth a quenching stream,

Hath softened that obduracy, and made

Unlooked-for gladness in the desert place,

To save the perishing (quoted Landow, 81).

This mode of reading cultivated certain habits of mind among Victorians (summary of the work of George Landow). Typology provided a poet with an array of “stock images” that could be drawn on and applied to fresh situations, sometimes quite different from the original setting of orthodox Christianity.

Typology implied a certain understanding of time and existence – that the past prefigured the future – and this contributed to “an entire worldview, an entire imaginative universe” (94). In a typological universe, everything had significance, no matter how trivial it may seem. In a typological universe, events in history, or physical realities, were replete with spiritual or transcendent significance. Typology provided a way for Victorians to hold together matter and spirit, earth and heaven, religious and political life in a complex unity.

For orthodox Christians, typology understood in this fashion was a way of affirming that all things have their coherence in Christ. For those who left orthodoxy but retained the typological imagination, it was a way of affirming the unity of the world, perhaps against the fragmentations of modernity.