Natural Law in the Second Trump Era

In recent years I’ve run into a lot of people, including Catholics, who are suspicious of the concept of “natural law.” They associate it with a kind of conservatism which they believe is dehumanizing and legalistic. The first issue most people associate with the concept these days is sexuality, and they associate natural law with “proper function” arguments against same-sex relationships as “unnatural.” Politically, many people these days identify natural law with the revival of “integralism,” a more extreme, robust form of political conservatism that rejects liberal democracy and seeks to build a unified society on Catholic principles.

And of course, many conservative Catholics (and other conservatives) do use the concept of natural law in this way. The voices speaking loudest about natural law in our society are typically those not only defending traditional Christian sexual morality but pushing for an aggressive, triumphalist political expression of Christian faith. Many of those people are happy about the fact that Donald Trump has just been sworn in once again as President of the United States. Trump’s administration will include a number of Catholics, including his VP J. D. Vance. His appointee for solicitor general, John Sauer, was a friend of mine at Duke, and I met him in a class on medieval philosophy when he was an undergraduate. (In fact, he gave me my first rosary and played a role in the early stages of my long process of converting to Catholicism.)

A Stark Contrast

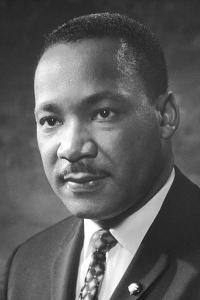

This year, two important events in the civic life of the United States fell on the same day: Inauguration Day and Martin Luther King Day. The contrast could not be more stark. The new President has signed, among many others, an executive order revoking an earlier executive order from 1965 which has served as a cornerstone for the federal government’s non-discrimination and affirmative action policies for decades. One conservative online acquaintance of mine has claimed (bizarrely) that Dr. King and President Trump have much in common. But in fact, President Trump has literally undone a civil rights measure dating from the lifetime of Dr. King.

I am sure that Vice President Vance and other Catholics in the Trump administration genuinely believe that this and other actions are in accord with natural law. Conservatives present “Wokeness,” “DEI,” and “CRT” as discriminatory, unjust ideas and practices that unduly favor some groups over others and promote an unbalanced emphasis on the welfare of perceived victims rather than an evenhanded justice toward all people. Or, in more extreme circles, others may argue that natural law actually dictates that the world be divided into nations comprising people of similar cultures who “seek each other’s good” rather than some supposedly “liberal” ideal of universal benevolence.

Martin Luther King and Natural Law

In contrast to this vision of natural law is the vision presented by MLK in “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” King was responding to white clergy who argued that his campaign of nonviolent civil disobedience was “untimely” and that breaking the law was never justified. To the latter charge, King responded by citing Augustine on the invalidity of unjust laws, and Aquinas on the need for positive human law to conform to “eternal and natural law.” While this kind of explicit reference to natural law in King’s work is rare, there’s a strong case that his moral and political thought as a whole is an expression of natural law theory.

Natural law as invoked by King is a revolutionary doctrine, a basis for the nonviolent “creative extremism” that he called for. The basic criterion he offers for determining whether a law is in accord with natural law or not is whether it “uplifts human personality.” In other words, what Catholic social teaching would call the dignity of the human person is the central principle of natural law. A little later he invokes Martin Buber to argue that segregation is wrong because it transforms people into things–an “it” rather than a “thou.” Based on this principle, all human laws and institutions can be evaluated for conformity to the principles of natural law, and any that promote dehumanization can and should be altered, and nonviolently defied until they are altered.

Alexander Hamilton: Chaos, Bloodshed, and Natural Law

Nearly two hundred years before the Letter from a Birmingham Jail, Alexander Hamilton articulated a similar view of natural law in a debate with an earlier conservative who appealed to the authority of positive human law. The Anglican clergyman Samuel Seabury (later to become the first bishop of the Episcopal Church) made arguments very similar to those of King’s critics. (Frankly, I think Seabury’s case stronger, and that of the revolutionaries weaker, than in the case of King, but that’s not the point here.) Whatever the wrongs suffered by the colonists, the evils of war far outweighed them. Or as Lin-Manuel Miranda paraphrased Seabury: “chaos and bloodshed are not the solution.”

Whether fairly or not, Hamilton interpreted Seabury’s arguments to be essentially the same as those of Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes believed that moral law was purely a matter of societal convention. In the state of nature there was no law–hence the famous characterization of such a state as “a war of all against all” in which human life was “nasty, brutish, and short.” In other words, law and morality depended on human government and its decrees. Hence Seabury’s anxiety about the consequences of the colonists rebelling against the established British government. Hamilton regarded this position as fundamentally atheistic and reproached the pious clergyman Seabury for holding it.

Rather, Hamilton argued, moral law fundamentally depends on God, who created human beings with an inherent sense of right and wrong.

Good and wise men, in all ages, have embraced a very dissimilar theory. They have supposed, that the deity, from the relations, we stand in, to himself and to each other, has constituted an eternal and immutable law, which is, indispensibly, obligatory upon all mankind, prior to any human institution whatever.

This is what is called the law of nature, “which, being coeval with mankind, and dictated by God himself, is, of course, superior in obligation to any other. It is binding over all the globe, in all countries, and at all times. No human laws are of any validity, if contrary to this; and such of them as are valid, derive all their authority, mediately, or immediately, from this original.” Blackstone.11

Good and wise men in all ages

We can argue about the relationship between the Enlightenment and premodern versions of natural law. Some Enlightenment versions, at least, were substantively quite different from the classic form of natural law found in Aquinas. But Hamilton’s appeal to “good and wise men in all ages” signals that his version is a fairly traditional one. I think MacIntyre’s criticism of Enlightenment ideology is fundamentally sound that MacIntyre is right to highlight the tradition-based nature of any concrete account of natural law. But the principle articulated by Hamilton in the paragraphs I quoted transcends the differences between an “encyclopedia” and “tradition” approach to natural law.

In other words, natural law is both a conservative and a radical theory. It’s conservative because it appeals to an eternal standard of right and wrong which does not, in principle, change with time (though our understanding of it may and does). It’s radical because it transcends any merely customary or “established” set of norms.

The postmodern mistake

The turn away from “essentialist” theories in general by Western intellectuals in the late 20th century is, in my opinion, a disastrous mistake that has helped pave the way for our present crises. Progressive intellectuals criticized any appeal to unchanging, transcendent norms out of the valid suspicion that people frequently appeal to such norms in order to give a sacred status to oppressive social structures. But like Samson, they pulled down the building on all of our heads. Again, MacIntyre offers us an alternative that acknowledges the valid insights of the postmodernists while rejecting the fundamental cynicism about “truth claims” that underlies radical postmodernism.

In the 21st century, it’s becoming clearer and clearer that debunking moral claims by reducing them to rhetorical ploys in defense of one’s own interests is a game that is heavily rigged to favor oppression, not liberation. The “new right” draws much of its power from widespread cynicism about the “cultural elites” and their pretensions of moral superiority. Nothing new about that, except that this time the “elites” have themselves sowed the seeds of this cynicism for decades.

As a result, we have this horrific phenomenon of a “conservatism” that openly embraces cynicism and irony, constantly “trolling” its audience while winking at a subset of demonic extremists within the audience. The people who engage in this rhetoric have learned too well that all moral claims are power plays. The original postmodernists made cynical, relativistic arguments out of a burning hatred of injustice and a desire to liberate people from oppressive structures. The new “conservatives” mouth the language of virtue and natural law while adopting fundamentally cynical and manipulative methods justified by the claim that their enemies are doing the same thing.

Escaping the hellish spiral

This creates a hellish spiral from which there’s only one escape, in my opinion. We must reclaim the language of natural law, the appeal to transcendent ideals. We must draw on the riches of our tradition (both Christian and secular/pagan) to formulate a moral and political agenda that will genuinely appeal to all people of good will. We must keep the focus on basic moral intuitions that are widely shared, such as that all people have inherent dignity, that children should not go hungry, that the accumulation of massive wealth is an injustice, and that nothing can ever justify the deliberate killing of the innocent. We must cut through the sectarian jargon used by ideologues on both sides and get down to the moral bedrock underneath the issues that divide us.

A true and liberating revolution against corruption and injustice is impossible without transcendent moral principles. Such principles have fueled every genuine movement of liberation in history. We have lost our way. We must reclaim it. We must become, in that sense, true conservatives, and only so can we become true radicals.

Images from Wikimedia Commons