I was raised in small town America, where Memorial Day meant parades, flag waving, flowers at the cemetery, and honoring of those who died in service to our nation. It was the Eisenhower era and we were patriotic, but not jingoistic. We loved our nation, but we recognized that others loved their nation as well. We waved the flag and affirmed that America was at its best when we worked together for a common cause that transcended our race and religion. We were “cold warriors” but wanted to prevent war. Our politicians were fallible, but we expected dignity and decency, and fair mindedness, from our leaders. We recognized that often there were two sides to every issue, and prized civility over bluster and bullying. We remembered the sacrifices of two World Wars and Korea and knew that citizenship meant sacrifice as well as freedom. While there was racism, there was also a spirit of generosity to immigrants and refugees.

In my Cape Cod village, one of the high points of the year is the Memorial Day Parade, starting in our church parking lot, where scouts, the high school band, bagpipers, fire trucks, floats, and classic cars gather, to begin their journey to the cemetery. But, this year, there will be no parades and pipers. We’ll have a grill and go to the beach in the morning, but this year we’ll wear masks and keep our distance from fellow beachcombers.

In considering Memorial Day this year, I am thinking of the universally invoked mantra, “we’re all in this together.” I am pondering the significant characteristics of those upon whom we depend – parents, grandparents, peacemakers, and peacekeepers. This year we’ve enlarged the circles of heroic sacrifice to include physicians and nurses, checkout clerks, first responders, meat packers, and farm workers, all of which have become essential to our wellbeing.

In light of this year’s pandemic, it is clear that sacrifice is one of primary characteristics of caregivers and protectors and that sacrifice is built into the nature of reality, or at least what it means to live a good life. We let go of certain things, so that greater things may come to pass. We defer gratification, so that others might flourish. We live simply so that others might simply live. We give up our time – and maybe even our lives – to protect the innocent and vulnerable.

Sacrifice is built into the graceful interdependence of life. Contrary to Ayn Rand’s rugged and metaphysically implausible individualism and nation-first ideologues, every achievement an individual makes is grounded in the sacrifices of others; some are sacrifices freely chosen, while others are tragically forced (for example, sweat shops and slavery). Sacrifice is essential to the wellbeing of the “body of Christ,” described in I Corinthians 12. The various parts consciously – and I want to underline the word “consciously” or “willingly” – choose to place their own wellbeing in relationship to the wellbeing of the whole body. The various parts find their wholeness in supporting the wholeness of the totality, which in turn nurtures each individual part.

Jesus proclaimed that there is no greater love than giving one’s life for another. This isn’t a matter of being a scapegoat, although there is much wisdom in the work of Girard and his followers; but a deeper recognition of one’s responsibility to sacrifice so that others may experience safety, joy, growth, and abundant life. Jesus followed the way of the cross, when other alternatives were possible, I believe, as a working out of his vocation and choice to affirm his calling so that we might have abundant life. Jesus’ sacrifice was neither compelled by God nor predestined but emerged from the alignment of his vision and will with God’s vision for abundant life for all creation.

Memorial Day has traditionally been about sacrificial living. Beginning first in the years following the Civil War, Memorial Day commemorated those who died in this tragic conflict. After World War I, Memorial Day was expanded to include all who died in service to their country. Initially, just military graves were decorated with flowers. However, over the years, many people also chose to decorate the graves of loved ones – fathers, mothers, children, brothers, and friends – on Memorial Day. This was an acknowledgement that “greater love” has many dimensions that go beyond military sacrifice.

While Memorial Day is a national holiday, it has profound spiritual lessons for us and invites us to deeper loyalties, even beyond nation and family, especially in these days of pandemic. It is about sacrifice and love of family and nation, not chauvinism and violence. If Memorial Day has a place in the liturgies or worship services of the church, its place is to inspire gratitude and remembrance for those who have sacrificed life and labor, and time, talent, and treasure, for the greater good.

The sacrificial love remembered on Memorial Day is about vocation and choice. It’s about going beyond self-interest to promote the wellbeing of the community and the world. As we look at the vocation of those who sacrifice on our behalf, we are challenged to beyond our individualism, narcissism, consumerism, and self-interest – and this may even include “American exceptionalism” or “America first” ideologies – to embrace the wellbeing of others, including the planet. We can celebrate our nation’s fallen heroes without being nationalistic. In fact, we must go beyond nation to balance patriotism with world loyalty and sacrifice largess and convenience for the healing of the planet.

Memorial Day is about remembering, and then dedicating our own lives to a larger, greater good for those we love, our nation – and this may mean protesting against military action, injustice, and enmity to immigrants – and the planet as a whole. It means protesting the rolling back environmental standards for the sake of profit and tax laws that favor the wealthy demeans the sacrifices of those who went before us and threatens the future of our children and grandchildren. Sacrifice, not self-interest, is the heart of Memorial Day. It certainly means sacrificing aspects of our freedom for the greater good – wearing a mask, practicing safe distancing, postponing indoor worship services, living more simply, and ensuring the wellbeing of your neighbors.

As you ponder Memorial Day, take time to ask the following questions: What sacrifices are you called to make for the greater good – in your family, among your circle of friends, and in your congregation, community, and nation? What sacrifices is your congregation challenged to make to ensure the wellbeing of vulnerable persons? What sacrifices are you called to make for the economically disadvantaged and food insecure in our land and across the globe? What sacrifices are you called to make for this good earth? How will you look beyond your own well-being to ensure the well-being of other peoples’ children, persons with medical risks, law-abiding immigrants, refugees, and the flora and fauna of our planet? This is the meaning of Memorial Day in a time of pandemic, and every time.

+++

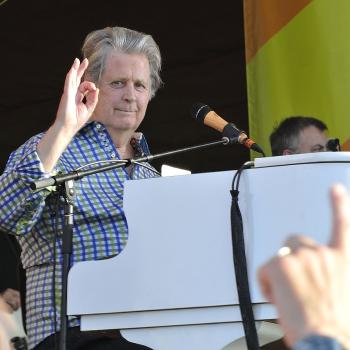

Bruce Epperly is a Cape Cod pastor, professor, and author of over 50 books, including FAITH IN A TIME OF PANDEMIC, GOD ONLINE: A MYSTIC’S GUIDE TO THE INTERNET, AND FINDING GOD IN SUFFERING: A JOURNEY WITH JOB.