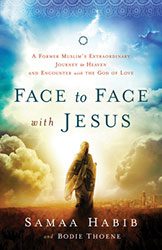

Samaa Habib’s Face to Face with Jesus: A Former Muslim’s Journey to Heaven and Encounter with the God of Love is a fascinating spiritual autobiography, describing one person’s encounter with the holy. It is a highly personal book with universal ramifications. It is highly particularistic and sectarian, yet it also has an unexpected globalism.

Samaa Habib’s Face to Face with Jesus: A Former Muslim’s Journey to Heaven and Encounter with the God of Love is a fascinating spiritual autobiography, describing one person’s encounter with the holy. It is a highly personal book with universal ramifications. It is highly particularistic and sectarian, yet it also has an unexpected globalism.

Like a growing number of spiritual autobiographies, Habib’s text describes a “near death experience” in which she encounters the divine. In this case, she sees the divine in the form of Jesus Christ, as understood by the Pentecostal biblical-centered movements of Christianity. In many ways, Habib’s description follows a typical pattern for “near death experiences” (NDE’s): she encounters a bright light, converses with a holy being, experiences a life review in which she becomes painfully aware of her imperfections, and is given the opportunity to choose whether she will remain in heaven or return to earth. She suggests that her return to this world is related to the prayers and needs of others, most especially her sister Adila. Her experience is authentic, yet equally personal and entirely her own, and not necessarily universal for all people.

Habib’s experience is life-transforming and may give us a glimpse of the afterlife. It is also profoundly intimate and individual. As H. Richard Niebuhr and others have noted, revelation is never generic, it is always particular. Whether found in scripture or mystical experience, revelation requires a receiver, and every receiver shapes the revelation in terms of her or his belief system, culture, and personal perspective. This doesn’t undermine the importance of our experiences, but simply our ability to claim that our experiences fully describe God. I can be fully convinced of a life changing encounter with God, while recognizing that the shape of the god and truth I encounter is always partial and perspectival.

Like the popular Heaven is for Real (Todd Burpo), Habib’s description of her NDE reflects a fundamentalist biblical perspective, accented by a sense that salvation comes through Christ alone. Many other NDE’s reflect similar experiences of divine love and life review, but are understood in more universalist Christian and new age forms. In these latter cases, the experience of Christ is continuous with saving revelations in other traditions, while Habib’s experience confirms her belief that no one encounters God in a saving fashion apart an explicit doctrinal or propositional relationship with Jesus Christ.

The particularity of revelation applies to Habib’s understanding of prayer. She sees prayer as supernatural and able to deliver us and others from life crises. On the battlefield of life, prayer is our greatest weapon and she describes many answers to prayer. Yet, in a curious way, Habib recognizes the relativity of her own prayers. In America, Habib confronts a very different climate. As she describes it, “as I was used to warm climates, the thought of a cold winter with snow seemed something I could not bear. I prayed that it would not snow….and the Lord answered my prayer! It did not snow. It was the warmest weather anyone had witnessed.” While I believe that our prayers can influence, at least to a small degree, our environment, would praying for a winter without snow be ultimately beneficial to the environment or overall human well-being? Would it work against the prayers and best interests of others? Does God favor some over others in such a partisan way? I happen to be a fan of the Boston Red Sox. However, if I pray for a Red Sox win, I am implicitly praying for another team’s misfortune.

Habib appears to recognize the relativity of her prayers and backs off from a total individualistic understanding of prayer when she realizes that her blessings can be problems to others. “Then the next year the drought was bad, and I thought about the farmers who needed the moisture of the snow for a good harvest. I realized that snow was a blessing. I prayed that it would snow. The Lord answered again. The winter was cold, and it snowed so much that it snowed even in April and May.” This, however, is also ambiguous, since it may have led to financial crises among lower income people whose finances were stretched by higher utility bills! One can appreciate Habib’s simple understanding of God’s answers to prayer. Yet, perhaps it is too simplistic and fails to realize the global and interdependent nature of life. It may also privilege our own interpretations of reality in ways that oversimplify the nature of causation, revelation, and divine providence.

Habib’s text is a lovely testimony to a certain interpretation of reality and a lively experience of the holy. Reality, however, may be much more complex and multifaceted and revelation more personal, pluralistic, and idiosyncratic than her interpretation suggests. I appreciate her conversion to Christian faith, but I also am aware of Muslims who see God as loving and personal, just as she sees the God of Jesus. I personally affirm a relational and personal image of God, but realize that many persons of faith see reality as universal and impersonal, for example, the spiritual parents of the practice of acupuncture that Habib finds helpful as a vehicle of Christian healing. Grounded in the understanding of chi, dynamic and interdependent energy, acupuncture suggests an energetic form of healing complementary to but not restricted to the personal vision of ultimate reality affirmed by Christian faith.

Habib’s encounters with the holy transformed her life and lured her to a new and more satisfying encounter with God. Still, similar experiences of the holy might inspire different understandings of the holy, perhaps more universalistic and pluralistic. That, indeed, may be the nature of revelation: it is healthy when we embrace its transformative power, but may become destructive when we identify our experience of the holy with the holy in its fullness and deny the saving power of other visions of the divine.

To read an excerpt, and more conversation on this book, visit the Patheos Book Club here.