Lectionary Reflections for the Third Sunday after Epiphany — January 27,2013

Lectionary Reflections for the Third Sunday after Epiphany — January 27,2013

Nehemiah 8:1-3, 5-6, 8-10; Psalm 19; I Corinthians 12:12-31a; Luke 4:14-21

A newly-ordained pastor once told me that her homiletics professor counseled that one should never preach solely on the Psalms. Her professor’s admonition struck me as strange then, and seems misguided to me today insofar as the Psalms were the primary worship resource of the Jewish people, central to Christian worship, and portray the many moods of the spiritual life. Psalm 19 is especially important for contemporary Christian reflection and captures the spirit of the Epiphany season. Epiphany proclaims the diversity of divine revelation while maintaining that there is ultimately no “otherness” in the many manifestations of divine creativity. We are one in the spirit and out of that unity emerges a joyful diversity. From this perspective, Psalm 19, read along with Psalms 148-150, is an insightful lens through which to interpret Jesus’ mission statement (the Spirit of God is upon me) and the Pauline image of the body of Christ. The non-human as well as the human worlds cry out for liberation, freedom, and healing; in the continuity of life, salvation pertains as much to non-humans as well as humans.

(For my process-relational commentary for this the Third Sunday after Epiphany, see http://processandfaith.org/resources/lectionary-commentary)

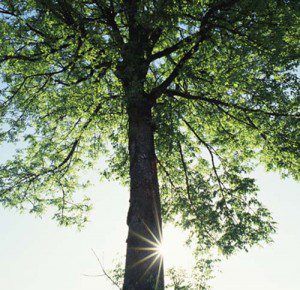

“The heavens are telling the glory of God; the firmament proclaims God’s handiwork. Day to day pours forth speech, and night to night divine knowledge….through all the earth.” The non-human world is the most profound and forgotten “other” for us. Humans have neglected, abused, and destroyed their natural environment. Theologians have justified the destruction of non-human animals by denying them spirit and experience. Essentially valueless, their sole purpose has been to serve our purposes regardless of the pain they might feel or the consequences for the overall ecology of life. In contrast, Psalm 19 asserts an essential inwardness to the non-human world, which is reflected in its ability to witness to God’s glory. The wisdom and experience we identify with human life is also present in the non-human world. As the final words of Psalm 150 proclaim, “let everything that breathes praise God,” that is, there is a divine presence in all things, evoking their ability to praise and pray.

Jesus’ first sermon could – like St. Francis’ speech to the animals – be addressed to the whole earth and not just humans. Nature is oppressed, imprisoned, and diseased. Non-human nature needs to share in God’s shalom just as much as we do. In fact, we are part of nature, different only in degree of experience not kind. In an interdependent universe, described by process theology, ecology, quantum physics, and Genesis 1-2, the “imago dei,” the image of God we see in ourselves is also present in the ambient non-human world. Apart from the impact of the non-human world, we could not exist, nor as philosopher Alfred North Whitehead asserts, can we discern a strict boundary between ourselves and the world around us.

If God’s healing touch does not include nature, then there is little hope for our own healing. As Romans 8 asserts, creation groans through us but also through our non-human companions. Our salvation, wholeness and restoration, and theirs is interconnected.

The adventurous preacher and liturgist might project photographs or moving images of the non-human world in tandem with words from Psalm 19, 148, 149, and 150. She or he might also project photographic images of nature in crisis, illuminated by Romans 8 assertion that creation in its entirety is groaning. Images of human and non-human animals caring for their children also witness to the fact that non-humans also love and care for their offspring.

Reflection on God’s glory spoken through the heavens – and revealed through pondering the night sky or photos from the Hubble telescope – reminds us that we are not alone in the universe. God breathes through plants and planets and turtles and toddlers. The “sin” identified most open throughout the Epiphany season involves the failure to see holiness in otherness. It involves seeing diversity as a threat, or something to control and manipulate, rather than appreciate and nurture. Psalm 29, along with the readings from I Corinthians 12 and Luke 4, challenge us to reclaim the living universe of childhood in which all things provoke wonder. Our task is to become gardeners of creation, inspired by beauty, and energized by the vision of healing the Earth. Surely one of the tasks of the church today – and one of its gifts to those who describe themselves as spiritual, but not religious – is to present a vision of healthy and creative Earth Care and planetary affirmation as reflective of an emerging theology and spirituality of creation.

(For more on process theologies of creation, see Jay McDaniel, Of God and Pelicans and Living from the Center, and Bruce Epperly, Process Theology: A Guide for the Perplexed and Emerging Process: Adventurous Theology for a Missional Church.)