[Editor’s Note: This is similar in subject to my Groundhog Day post. Classic comedies lend themselves well to such a treatment since they almost always end in marriage. I think St. John Paul II would be very pleased by this one.]

When Harry Met Sally tells the story of two less-than-friendly acquaintances who through twelve years of chance meetings, witty exchanges, and plenty of give-and-take, finally stumble into love with one another. Decades after its premier, the classic romantic comedy consistently draws audiences. Perhaps they are intrigued by the question posed on the movie poster: “Can two friends sleep together and still love each other in the morning?” The question is two-fold: Can friends sleep together? And, can they “love each other” afterward? It appears a matter of friendship on one hand and a question of sexual relationships on the other. A satisfying answer requires an account of both. The conclusion of the film gives a somewhat surprising response: friendship and sex are not—and should not be— mutually exclusive. Although, they don’t quite mix in the ways typically encouraged by contemporary culture. In short, two friends can absolutely sleep together and still love each other in the morning. . . if they’re husband and wife.

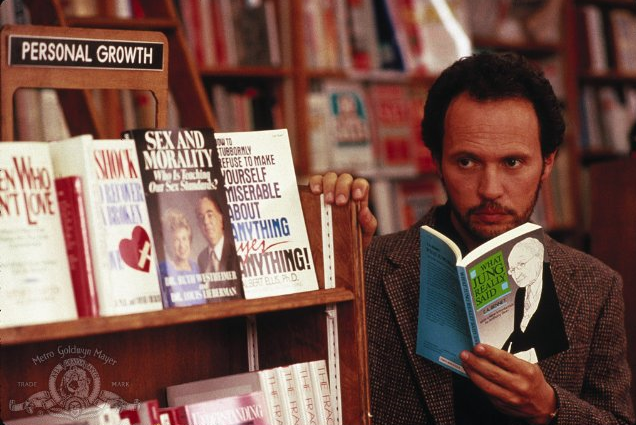

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vmSpCLefjnwHarry Burns and Sally Albright first meet after college graduation while en route to New York City—a symbolic destination. New York upholds the promises of modernity, offering worldly experiences that Sally and Harry have been taught to value. Presumably, they expect a fulfilling lifestyle defined by independence and autonomy. Yet Harry and Sally, like all human beings, will not be satisfied with solitude. They innately long for connection with others. This is obvious when Harry “makes a pass” at Sally (even though she vehemently rejects it).

Sally is upset at the thought of Harry’s interest in her because he is “going with” her friend. Undaunted, Harry asks a second time if the two can “stay the night in a hotel.” This conversation reveals each characters’ dominant traits. Harry is motivated by his passions. He is a slave to sensuality. Sally is motivated by her feelings. She values loyal friendship and symbolizes sentimentality. As they argue, the two positions seem so opposite that Harry and Sally can no longer be friends. They agree on a rule to guide the rest of their encounters, “Men and women can never really be friends because the sex part always gets in the way.”

Harry and Sally’s rule correctly identifies the problem of concupiscence, or the human tendency to sin, which John Paul II’s work Love and Responsibility more narrowly defines as “the consistent tendency to see persons of the other sex through the prism of sexuality alone.” In particular, Sally is tempted to sin by using others as objects for emotional gratification and Harry tends to use them for his own physical pleasure. When faced with the obstacles presented by their flawed human nature, Harry and Sally choose to forgo friendship altogether, concluding that it is impossible—or at least too difficult—to overcome the temptations.

Harry and Sally’s pessimistic attitude is not wholly out of place. With their characters as they are, acting as embodiments of sensuality and sentiment, they are unequipped to overcome their personal temptations. When they meet again, this is still the case. Sally is an up-and-coming journalist who is head-over-heels for her live-in boyfriend, Joe. However, her contentment will not last. Sally’s attachment to her partner is based completely on sentiment. According to John Paul, sentimental relationships are cases in which “the person is less of an object than an occasion for affection” (LR 113). The value of Sally’s relationship is the emotional gratification she receives from it. She later explains to Harry how she was willing to give up having children in order that she and Joe could be spontaneously romantic and “fly off to Rome at a moment’s notice.” When they never do, Sally becomes restless. After experiencing a happy day with a friend’s child, she changes her mind, believing a family will offer her the happiness she has not found. Even though a desire for family is good, Sally’s motives are impure. When Joe refuses to do what will give her pleasure, Sally leaves. Her ever-searching and ultimately selfish lifestyle leaves Sally empty and without real human connection.

While Sally’s overly sentimental nature causes her unhappiness, it is excessive sensuality which damages Harry’s relationships. At their second meeting, Harry tells Sally that he is “madly in love” with his fiance, Helen. Although, later, it seems likely that the intensity of his attachment to Helen was based primarily on sexual desire rather than lasting companionship. After just a few years of marriage, Helen suddenly demands divorce. Harry finds that his wife has been sleeping with another man. He feels the inconstancy of sensual “love” as he asks Helen if she still loves him. She painfully replies “I’m not sure I ever loved you.” After his marriage ends, Harry continues to indulge his sexual appetite, but just like his failed loveless marriage, a series of loveless sexual encounters also fails to satisfy him.

Harry and Sally find themselves in similar places: alone and disappointed. With nothing to lose, they throw out the unsatisfying rule they once made and decide, at last, to try and become friends. They succeed! The two develop an honest friendship in which Harry “can say anything to her.” They are fulfilled in the experience of coming to know one another.

Gradually and unknowingly, the two become increasingly attached. Their influence on each other becomes stronger and begins to take the form of love in the sense that their “life together [has become] as it were a school for self-perfection” (Love and Responsibility). Harry takes on the sentimental qualities of Sally as he becomes attached to her in ways that transcend the physical. Sally, in turn, becomes more ‘sensual’ in a moderate sense, meaning that she becomes more aware of and ordered toward the other, instead of remaining concerned with her own feelings and desires. (To clarify: Theology of the Body points to awareness of the sexual urge as a good partly because one of its functions is to bring one outside of himself.)

But Harry’s sensuality cannot be cured by introducing sentiment, and Sally’s sentimental tendencies cannot be balanced by heightened sensuality. There is indeed a call for integration in Harry and Sally’s relationship, but more is needed beyond merely reconciling their two personalities. Simply mixing sentiment and sensuality in the proper ratio does not yield a real love. Pope John Paul explains, “Experiences which have their roots in the sensuality or natural sensibility of a woman or man constitute only the ‘raw material’ of love.” According to Theology of the Body, in order to become a complete love Harry and Sally must work to “introduce love into love.” Unfortunately, they go about it improperly. When sensuality and sentimentality do finally meet, they come together in worst way possible.

At a moment of weakness, when Sally is vulnerable and Harry off-guard, the two sleep together. They let “sex get in the way.” And, they certainly do not seem to love each other in the morning. Their friendship suffers. They don’t speak for months. Instead of sealing their friendship into a deeper love, sex somehow fractured it. Does this mean that integration is impossible? Is the original rule proven true? Can men and women never really be friends?

No.

While Harry and Sally may appear to have put together the necessary pieces of love (sentiment and sexual passion) they left out the main ingredient: sacrifice. A real love requires unconditional commitment. JPII puts it well. With any relationship, “what it becomes depends upon the contribution of both persons and the depth of their commitment.” At the end of the film, Harry realizes this. Loving Sally properly includes complete commitment, a self-sacrifice that allows for full integration in the spousal union of the two. The very moment he sees Sally again, Harry makes clear his intentions: “When you realize you want to spend the rest of your life with someone, you want the rest of your life to start as soon as possible.”

This time, Harry is not willing to forego friendship with Sally even after “sex got in the way”. He wants to redeem it. He has the will to overcome. In the end, When Harry Met Sally proves a testament to our human potential for extraordinary and sacrificial love. It exposes the claims of modernity about sex, love, and relationships for what they are—erroneous and empty. The story has a happy ending only in marriage, showing from experience the truth that John Paul’s theology affirms: “man can only find fulfillment through a sincere gift of self.”

***

Matalyn (Mattie) Vander Bleek is a Junior at Hillsdale College studying Political Philosophy with a minor in History.

***

You can read more about the Theology of the Body here.