What happened to the love song?

Though seemingly every song on the radio these days is about what we might call carnal camaraderie—the mutually enjoyable meeting of two hard bodies—very few are about real love. Lady Gaga, as good a candidate as any for the title of Queen of Contemporary Pop Music, rhapsodizes poetic about a characteristically extortionary and emotionally avaricious relationship: I won’t tell you that I love you/Kiss or hug you/Cause I’m bluffin’ with my muffin … Just like a chick in the casino/ Take your bank before I pay you. Love in this understanding is a zero-sum game, and the advantage of one player requires the disadvantage of the other. Such a love can only ever be insecure and tenuously held.

Music is moral, of course, and inasmuch as teens and twenty-somethings consume a steady diet of this trash, they dull their ability to differentiate romance from gamesmanship, love from abuse.

But the opposite tendency is at least as dangerous, too. Sappy crooners like Cole Porter idealize romance into something gauzy and sugary, as easy as it is carefree. When Porter sings in his classic “It’s De-Lovely,” for instance, that, “The night is young, the skies are clear/And if you want to go walkin’, dear/It’s delightful, it’s delicious, it’s de-lovely,” he gives voice to a sort of soft hedonism that leaves young lovers unprepared for the hard sacrifices, the inevitable self-death involved in genuine love.

So those best love songs, then, are those that manage to give voice to the dual—even contradictory—tendencies inherent to the romantic experience: love and loss. There is an obvious and true sense, of course, in which entering into love makes one more whom one was meant to be, oriented as we are towards communion both bodily and spiritually with others. But there is an unavoidable sense, too, in which love of another brings one out of oneself, causes one to offer oneself up for the sake of another (even if both are ultimately offering themselves up to the glory of God), and this offering up involves an abdication or nullification of the self-interested will. We become attuned to the motivations, foibles, and inclinations of the beloved, and in doing so expose ourselves to feel with them. Empathy, then, comes at the cost of the security and certainty of a self-oriented life—which at times can seem quite a high cost to pay. And meanwhile this essential giving over is tinged always by a degree of heartbreak, since all things, including the beloved, pass away in this life.

If the sentimental style of mid-century crooners is all love and no loss, and today’s debased pop artists are mostly loss with no love, the truest love songs manage to convey both emotions simultaneously. This dual love is reminiscent of Christ’s own love for us, which takes its form on the Cross, at once a victory and defeat. Christ’s love is tragic, in one sense, because it requires a sacrifice from He who owes no debt, but is obviously also happy, in that it provides us a path to life beyond death. And as Pope Saint John Paul II teaches us, “by sharing in the sacrifice of the Cross, the Christian partakes of Christ’s self-giving love and is equipped and committed to live this same charity” (Veritatis Splendor, 107). But as we are creatures caught up between life and death, our own capacity for love is both limited—and therefore tragic, and oriented beyond ourselves—and thus constructive.

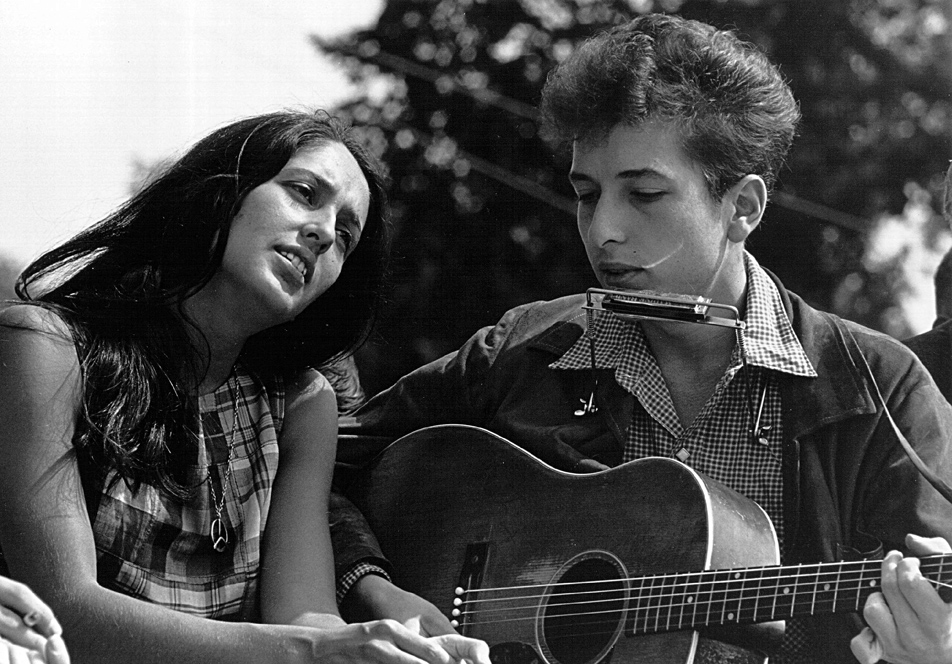

One classic artist, at least, seems to grasp this point about the restless and transient nature of earthly love. Bob Dylan’s recent album, “Shadows in the Night,” takes its tracks from the Great American Songbook, that canon of quintessentially American ditties devoted to love, pain, hope, and hardship. With songs like “I’m a Fool to Want You,” “That Lucky Old Sun,” and “What’ll I Do?” Dylan’s album showcases a particular brand of love song—tender but tragic. And in a telling exchange with a reporter recently the great songwriter reflected on the power of these songs. The question and answer are both worth repeating in full:

Q: These songs conjure a kind of romantic love that is nearly antique, because there’s no longer much resistance in romance. That sweet, painful pining of the ’40s and ’50s doesn’t exist anymore. Do you think these songs will fall on younger ears as corny?

A: You tell me. I don’t know why they would, but what’s the word “corny” mean exactly? These songs are songs of great virtue. That’s what they are. People’s lives today are filled with vice and the trappings of it. Ambition, greed and selfishness all have to do with vice. Sooner or later, you have to see through it or you don’t survive. We don’t see the people that vice destroys. We just see the glamour of it — everywhere we look, from billboard signs to movies, to newspapers, to magazines. We see the destruction of human life. These songs are anything but that. [Emphasis added]

There’s some deep wisdom behind this question because it realizes the great shift that has occurred in modern romantic relationships, which now try to optimize convenience and pleasure while preventing the parties from experiencing any real emotional risk. The interviewer’s question suggests that this contractarian arrangement, devoid as it is of the “resistance” of traditional romance, robs the relationship of its basic characteristic. Why should “two consenting adults,” as the phrase goes, have to “resist” each other about anything? Not only that, the question suggests that young people today literally won’t understand older notions of love tied up with sacrifice and restraint—difference begets incomprehensibility.

But anyone who has truly loved another knows the “painful pining” that the interviewer asks about here. Love cannot be managed from a distance, it requires participation. Love springs forth with its own momentum, momentum which the lovers must either choose to harness or reject: “The attitude toward other persons depends largely on the way spontaneous feelings for them are handled, the way some feelings are cultivated and others are controlled” (The Truth and Meaning of Human Sexuality, 54). A relationship that calls forth pain, then, is precisely one that is succeeding, not failing.

And Dylan’s answer is itself remarkable, inasmuch as he doesn’t just appropriate the interviewer’s premise, but claims that the sort of love he’s talking about is indeed a “great virtue.” He suggests that this sort of love—sacrificial, uncalculated, tragic—actually makes one into a better person, that it frees one from the fetters of sin. Such an idea resonates with JPII’s idea of spiritual progress, when he writes that eventual spiritual “perfection demands that maturity in self-giving to which human freedom is called” (Veritatis Splendor ,17, emph. added). For Dylan to make this point to a generation raised on odes to nihilistic hedonism displays great deal of optimism in the basic nature and orientation of the human spirit.

“We don’t see the people vice destroys,” Dylan says. Millions of souls fade away little by little into nothingness, like the sinful ghosts in Lewis’ Great Divorce, instead of achieving the greatness they are called to in the fullness of love and thereby acquiring real substance. Like any of the chart-topping tunes that fill up airwaves for a time only to be forgotten after a few weeks, too many people similarly chase easy thrills and cheap pleasure while neglecting that which can alone satisfy their hungry hearts. There is something for Dylan ennobling about genuine love, which is, again, a hard love.

And, indeed, his music—timeless, often tragic, and always true—achieves more than the vacuity of the age. Its enduring popularity and power is a testament to that. It is, as we ought to strive to be, oriented beyond but grounded in our own tragic in-betweenness.

***

Travis LaCouter writes from Washington, D.C. He graduated from the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts. His work has appeared around the web at First Things, Ethika Politika, Philanthropy Daily, and elsewhere.