Tongues

James 3:4-5 offers this:

Or look at ships: though they are so large that it takes strong winds to drive them, yet they are guided by a very small rudder wherever the will of the pilot directs. So also, the tongue is a small member, yet it boasts of great exploits.

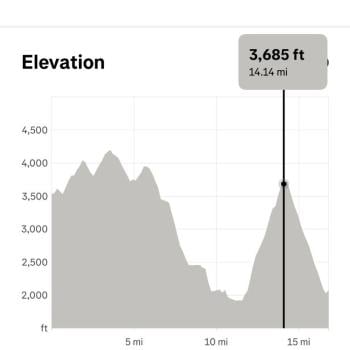

One of the more intimidating spiritual practices I have avoided as a contemplative is the silent retreat. Silence and ADHD are not compatible playmates. This is not to say that I have not done a silent retreat, many of my long runs are done alone and it can be a long 6-8 hours of me and my thoughts. But to go to a weekend retreat with other people and not talk the whole time, that is a whole different animal.

This week, I want to talk about the notion of silence as a spiritual practice.

I was recently the Rule of Saint Benedict and the reading schedule had us pause upon Chapter 6, On Restraint of Speech:

1 Let us follow the Prophet’s counsel: I said, I have resolved to keep watch over my ways that I may never sin with my tongue. I was silent and was humbled, and I refrained even from good words (Ps 38[39]:2-3). 2 Here the Prophet indicates that there are times when good words are to be left unsaid out of esteem for silence. For all the more reason, then, should evil speech be curbed so that punishment for sin may be avoided. 3 Indeed, so important is silence that permission to speak should seldom be granted even to mature disciples, no matter how good or holy or constructive their talk, 4 because it is written: In a flood of words you will not avoid sin (Prov 10:19); 5 and elsewhere, The tongue holds the key to life and death (Prov 18:21). 6 Speaking and teaching are the master’s task; the disciple is to be silent and listen. 7 Therefore, any requests to a superior should be made with all humility and respectful submission. 8 We absolutely condemn in all places any vulgarity and gossip and talk leading to laughter, and we do not permit a disciple to engage in words of that kind.

Silence

Silence is powerful. I remember a hike I was on with my 17-year-old last summer. We were in a section of woods that was particularly secluded from human made noises, a rarity today. I remember her recalling how silent it was. In my younger days, these natural areas were much more abundant. It has always baffled me how overwhelming these silent areas are. There is some evidence for this.

In an article in the Smithsonian Magazine in December 2013, entitled Earth’s Quietest Place Will Drive You Crazy in 45 Minutes, the authors describe a room that is supposedly the quietest place on earth, an anechoic chamber at Orfield Laboratories in Minnesota, is so quiet that the longest anybody has been able to bear it is 45 minutes. I am not sure about the 45 minutes, but as a contemplative, I know that the mind tends to wander in about 5 minutes or less in silent meditation and takes a tremendous amount of training to gain “control” of the mind. One thing that the article points out is that as the ears adapt to the sound, we adapt to the sound and become the sound.

If you have been around me for a while, you will know I tell the story about how I almost ended up in the monastery. From the ages of eighteen to twenty, I contemplated Catholic priesthood and the monastic life. I actively courted the Benedictines and the Redemptorists as potential orders. I was about a year out from making novitiate vows when I met a pretty red head who fed me tacos.

The Spiritual Practice of Silence

In those two years, I spent a lot of time praying my rosary, reading the Psalms, doing the work that my vocation directors asked me to do and generally being a devout Catholic. After meeting my wife, I left the Catholic church and became a Methodist and was an itinerant preacher for 20 years in a variety of roles. The one lesson that I have taken with me all these years is the power of prayer and silence.

In 2017, after being away from any formal contemplative formation, I took up studying to get a certification in Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction. The culminating project at the end of the course was a day long silent retreat where I had to practice all the forms of meditation that I had learned in the course. The day was a long day of silence, walking and thinking. No phones, no kids, no jobs, nothing but me and God.

In all of this practice, the greatest thing I have learned is that God is not something that is outside of us. God is something that resides in all of us. Through contemplative silence, we begin to see how great God is, how God’s greatness resides in us. In all our ugliness, our self-doubt, our fears and our anxieties, contemplative silence strips us and if we can come to our centering breath, we see that we are none of these illusions. We are the greatness of God’s love. We are God’s beauty.

Borrowing from the Brussat’s Spiritualty and Practice, they offer these suggestions for increasing your practice of silence:

- Turning off a television, a radio, or a portable media player is my cue to practice silence.

- Seeing someone meditating is a reminder that I must incorporate silence into my daily routine.

- Noting the silences in my conversations with others, I vow to use silence as a bridge rather than as a barrier.

We talk too much and listen too little. In my practice as a therapist, I offer that listening happens more than with your ears. It happens with what you see and feel from the world around you. Turning off the television, turning down your music or putting down your phone is a physical posture that helps you listen better and creates a space of silence in your life.

Learning to listen to be a beneficial presence rather than to listen to offer a thought or suggestion is another practice of silence that our society has forgotten how to do. It is one that I am actively engaged in daily as a meditative practice, one hour at a time.

Centering Prayer

A well-known prayer used in Centering Prayer is this prayer. The idea is to repeat the prayer like a mantra, dropping a section at a time until you get to the word, “Be”. At which time, you sit and meditate on the notion of being:

Be still and know that I am God.

Be still and know that I am.

Be still and know.

Be still.

Be.