It was only after I memorized Portia’s lovely speech for Mrs. Matson, my exacting senior English teacher, that I learned the actual meaning of its first line: “The quality of mercy is not strain’d.” “Strained” meant “forced or constrained,” and the line insists simply that mercy cannot be wrung from God or others by force, but must be freely given. No law compels a judge or an adversary to be merciful: the law is about justice. Mercy transcends justice when it “droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven upon the place beneath,” blessing “him that gives and him that takes.” Though The Merchant of Venice is a troubling play sullied by a distressing strain of anti-Semitism, its famous reminder of the wisdom of mercy still presents an eloquent appeal to reach beyond an ethic of strict justice to a wider, more generous understanding of what we need from God and each other.

But mercy can’t be constrained, as any parent knows who has tried to appeal to a small child to get beyond “That’s not fair!” and understand that the offending playmate may be hurting or sad. It’s a delicate business: “fair” is a good standard to hold on to. We want children to learn to be fair. There can be no mercy without justice: socially, legally, psychologically justice comes first. Debt forgiveness assumes mutual recognition that a debt is owed. A sentence can be commuted only if a sentence has been pronounced, and a commuted sentence doesn’t pretend that the judgment was wrong—only that a greater good may be served by extending mercy.

I have depended on other people’s mercy when I have disappointed or failed them. I am among the many who can sing with conviction that I’m “standin’ in the need of prayer,” and of gracious, imaginative understanding. Because of that I have come to believe that the only way to be truly merciful is to recognize how often and undeservedly I have received mercy. I can afford to give what I have so abundantly received.

In Exodus—another unsettling story—the Lord says, “I will have mercy on whom I will have mercy . . . “ insisting that divine generosity is not to be limited by any human notion of justice, or by any human measure of “just desserts.”

Mercy is not rational. It is wisdom of the heart, not of the mind. And, as Portia points out, “earthly power doth then show likest God’s when mercy seasons justice.” Mercy is, in a sense, a privilege of the powerful. To live mercifully is to recognize our own empowerment as children of God, as free agents, as the fortunate who have been “twice blessed.” And to recognize also how we need mercy from the oppressed from whom our privilege has been stolen.

Portia’s appeal to Shylock may be misdirected. But it widens where she reminds him that “in the course of justice, none of us should see salvation.” For that brief moment she aligns herself and all those she defends with the one among them who has been so despised. It is a flicker of the solidarity that is called for now, in a season of political hostilities, deportations, xenophobia, threats, and fear. Mercy for those whom the law condemns where the law has not served them well, mercy for those who have crossed borders in the dead of night to save their lives, mercy also for those whose political positions we find incomprehensible, even as we oppose them, because we are in no position to judge their motivations: none of these can be constrained. But it may be in these varieties of mercy that we find our way through to a peace we can only begin again to imagine.

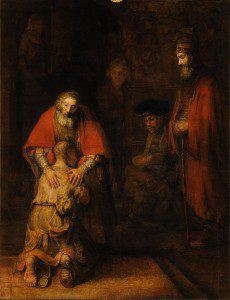

Image: Rembrandt’s Prodigal Son, wikipedia.com