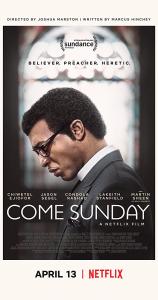

Come Sunday,” premiering April 13 on Netflix, does what I’ve long asked for in movies about faith: It observes Christian doctrinal disagreements with intelligence, grace and love. It just happens that the protagonist’s stance is one that many believers consider heresy.

In an age where movies about faith — including “I Can Only Imagine” and “God’s Not Dead 3” — seem to debut every week, “Come Sunday” is easily one of the more skillfully made. And yet, its main character’s message that “you don’t need to be saved” will likely send more than one viewer scrambling for the remote.

Dangerous doctrine

“Come Sunday” is the story of Rev. Carlton Pearson (Chiwetel Ejiofor), a minister in Tulsa and an apprentice to Oral Roberts (Martin Sheen). Pearson caused a national stir in the late 1990s when he preached that there was no hell (the real Pearson can also be seen in “The Heretic,” a documentary about Rob Bell, whose “Love Wins” argued similarly). Pearson’s new teaching divides his church, fractures his friendship with his associate pastor (Jason Segel) and threatens a once-promising career.

There’s a famous quote in Christian circles, often attributed to Augustine, that says:

“In essentials unity, in non-essentials liberty, and in all things charity.”

It’s one of my favorite quotes because it’s a reminder that, as we Christians, don’t always agree on everything, and for the most part, that’s okay. I hold differing views from many fellow believers on everything from politics to drinking to watching R-rated movies, and that’s fine. There are also theological disagreements I might hold to a little more tightly — such as evolution or some of the tenets of Reformed theology — but I don’t consider disagreement with them to a breach of faith.

The existence of hell, though, is a different matter. If there’s no hell, it changes our view of what happened on the cross, the necessity of repentance and God’s very nature. I don’t have the resources, depth of knowledge or time to go into a doctrinal dissection of hell, but I hold to a traditional Christian teaching that it does exist. The very idea of being saved implies that I’m being saved from something, and to believe in a God who looks away from sin and says “everybody’s in” might sound nice on the surface, but it ignores the yearning for justice we all have. Proponents of theology like Pearson holds assume they’re doing away with the idea of a monstrous God; in truth, they’re robbing him of his sacrificial love, holiness and justice, and minimizing the impact of our sin.

I’ve likely oversimplified or partially misrepresented Pearson’s beliefs. And if I have, I apologize. The film goes to pains to say that he doesn’t believe all humans don’t need to be saved; simply that it’s already done. Everyone will get in and the idea of hell is a sort of hell on earth for people who live selfishly. It’s universalism, very similar to what Bell writes about in “Love Wins.” I don’t have the biblical scholarship to parse the nuance of Pearson’s beliefs — he apparently believes in sin and the need for redemption, but disagrees as to how it’s secured — or to emphatically state that what he believes is heresy. But there’s enough hesitation in me to feel comfortable thinking this belief co-exists with orthodoxy. (For a good dialogue on this, and with an eye toward balance, I would read both Love Wins and Francis Chan’s response, Erasing Hell).

The movie doesn’t necessarily help with that, as drama is obviously a poor place to explore the nitty-gritty of doctrine. In the film, Pearson believes God spoke to him after watching a news report about a tragedy in Africa. He doesn’t lay out a biblical foundation for it, other than quoting a passage in 1 John (the movie also counters with Romans 10:9, arguing that we must confess Christ to be saved). It ignores the fact that Jesus talks about hell more than he does Heaven, and that the apostles obviously believed there was urgency in telling others about Christ.

I don’t say this to the movie’s deficit, as we’ll get to in a moment. The responsibility of “Come Sunday” is not to make an argument for or against hell, but rather to show how the change in beliefs impacted Pearson. But the movie’s explanation for Pearson’s beliefs sides not on a preponderance of scriptural evidence, but cherry-picking verses and relying on an experience only Pearson claimed to have — an experience that occured in the midst of intense emotional trauma and that no one else witnessed. And given that I’m sure the movie had to simplify things, which are likely expounded on in Pearson’s book on his beliefs, which I have not read.

I understand why people want to believe there’s no hell. It would make our faith a lot less offensive and troubling, and it would give us a lot of reassurance when we consider family members and friends who passed away without knowing Christ. And Christians have used hell to manipulate, exploit and coerce people for years; we’ve abused this doctrine for our own benefit. If I get to Heaven and find that I was wrong, I won’t mind. And there’s a lot of mystery and areas where I have to say “I don’t know,” particularly concerning young children who die, deathbed confessions, people who die without ever hearing the Gospel. I want to believe there’s no hell; I just can’t.

And so, Pearson’s viewpoint is one I just can’t bring myself to agree with. But that does not mean “Come Sunday” is not worth your time. In fact, its emotional impact is all the more impressive considering my disagreements.

Graceful dialogue

It’s not surprising that “Come Sunday” is technically impressive. Director Joshua Marston debuted with “Maria Full of Grace,” a heartrending 2004 indie about a woman who resorts to drug trafficking to provide for her family. He’s gone on to direct acclaimed TV shows such as “The Newsroom,” “The Good Wife,” and “American Crime.” While the direction in “Come Sunday” isn’t showy, Marston shows a knack for portraying theologically rich conversations with grace and heart.

Based on a story originally showcased on“This American Life” (Ira Glass is one of the film’s producers), the film is less a diatribe about factions in the church or stodgy Christians clinging to the idea of hell, but a character study about what happens when those entrenched in faith communities begin to change their views. My position on hell may align with the majority of Christian I know, but I’ve experienced the rift that comes with changing political stripes or loosening my grip on other theologically beliefs. When there is a fracture in a faith community, it can hurt as much as a family split. And for those like Pearson, whose livelihood depends on this community, the ramifications of taking a stand can be devastating.

In this climate, it would be easy to expect that a film about such a spiritual hot potato would be heated and loud, but “Come Sunday’s” greatest success is the way it manages to convey grace and love even in disagreement. Yes, Pearson’s church splits, but the relationship between him and Segel’s character, Henry, is portrayed with kindness and warmth. Even Oral Roberts, a notoriously problematic individual, is portrayed not as a one-note villain but as a flawed human being. Pearson isn’t held up as a lion of the faith but a man with his own contradictions, someone who believed God would bring us all into Heaven but had trouble dealing with a dear friend and parishoner’s (Lakeith Stanfield) homosexuality.

Marston ably captures the dynamics of a Pentecostal church service and navigates the racial tensions in congregations without making them the film’s focal point or resorting to cliche.The film might have doctrinal division as its main draw, but Marston also touches on the church’s problematic relationship to the LGBT community, diversity in the church, and the toll a life of ministry can take on a family. He’s helped along by solid performances from Segel, Stanfield and Sheen, who take characters who could have been ciphers and grant them humanity and complexity. But towering above everything is Ejiofor, who vibrates with electricity in his preaching scenes and conveys the emotional turmoil Pearson is embroiled in in the quieter moments. It is a complex, nuanced performance that never goes for easy dramatics but instead crafts a well-rounded, real character.

Were “Come Sunday” debuting in theaters, I imagine it might be a lightning rod for controversy, with picketers protesting and evangelicals descending on talk shows to condemn it. I hope its release on Netflix allows others to come to it with no agenda. You may disagree with its main character — as I’ve said, I do. But the film is so much more that its subject’s controversial teachings. It’s not about something we disagree with but the way in which we disagree, and it’s a picture of church life that feels more real and dramatic than we often see on the screen. It’s not to be missed.