MMW thanks Dianna for the tip!

This was written by Jehanzeb and was originally published at Broken Mystic. This has been edited for length; you can read the post in its entirety here.

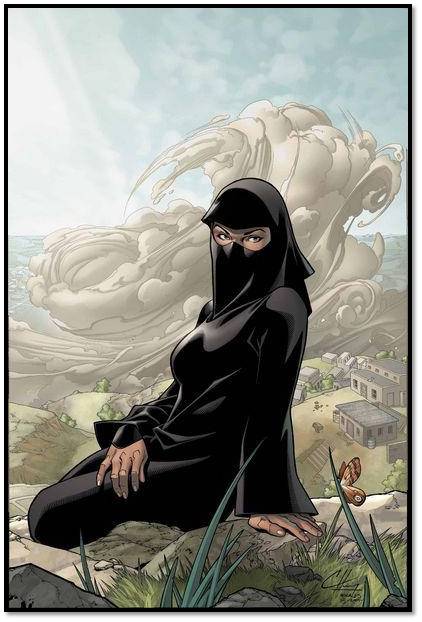

Meet “Dust,” or Sooraya Qadir, a burqa-garbed adolescent Afghan girl who has the ability, as shown in the scene above, to shape into sandstorms and tear the skin off her enemies. She has been a member of Marvel Comic’s X-Men since her first appearance in 2002 and she currently appears regularly in the “Young X-Men” comic books. In the male-dominated world of comic books, where female characters are depicted with large breasts and skimpy skin-tight (or lack of) clothing, it’s interesting to examine whether or not Dust and other Muslim super-heroines escape the sexual objectification and sexism that women often suffer in comic books. Are the Muslim women subjected to stereotypes? Are they doomed to the same fate of other female characters? Does the “male gaze” still apply? In Part 1 of this essay, these are but a few questions that we will apply to the character of Dust, and as we shall learn, the answers are fairly complex. In Part 2, we will explore other Muslim female characters where unfortunately, there is hardly any improvement.

In regards to Dust, the “X-Men” is the perfect place to accommodate a Muslim character. X-Men fans, or those who have seen the films, already know that the storyline centralizes on how mutants – evolved and “gifted” humans with superpowers – are discriminated against by other human beings. Mutants are misunderstood, feared, and hated by the public, while the media and government powers promote ignorance, persecution, and even war upon them. Sound familiar? Recall the opening scene from X-Men 2 when a mind-controlled Nightcrawler nearly assassinates the President of the United States and the television headlines scream: “Mutants Attack the White House.” I remember when I first saw that scene I couldn’t help but think of September 11th. What made me relate even more to the scene was how the X-Men – mutants who had absolutely nothing to do with the attack – were crowded around the television and watching this news report and feeling as if they were responsible. X-Men producer Lauren Shuler Donner even explicitly stated on the DVD for X-Men 2, “If there is any oppressed minority—homosexual, religious, Muslim, whatever it is – that is the most absurd question that people do ask: ‘Can you try not to be who you are?’ And so we felt it was very important to show this whole absurd side.” So considering how relevant “X-Men” is to current events, how does Dust fit in at Professor Xavier’s Institute for Gifted Youngsters?

Grant Morrison, the X-Men writer who created Dust, said in an interview, “It can only happen at Marvel. As Wolverine comes closer to unlocking the dark secrets of his past, an Afghan Muslim mutant joins the X-Men. You want daring? You want different? Then meet Dust as New X-Men challenges the rules again.” Though the word “awesome” may initially spring to mind when one reads this statement, it can be strongly argued that the male gaze is still in effect. For those who are unfamiliar with the terminology, the “male gaze” is essentially female characters being depicted and presented in ways their heterosexual male writers, artists, and audiences would like to see them. In the case of Dust, we can make an argument for the western male gaze: an “oppressed” Muslim girl is rescued from Afghanistan by Wolverine, a western male mutant. Wolverine is told that the Taliban were trying to remove Dust’s burqa, obviously to molest her, and since there doesn’t seem to be other Muslims around to take a stand against the Taliban’s perverted behavior, who better to rescue her than Wolverine, or shall I say, western democracy? The scenario of Dust fighting the Taliban, as admirable as it is, occurs enough times in later issues that it makes the point that this is how western male writers, artists, and readers want to see a Muslim super-heroine, i.e. to rebel against her oppressors, the mutual enemy of the U.S. government.

To support this argument even further, there are many factors to consider, including political context. For example, Dust makes her first appearance in New X-Men # 133 which was published in December 2002, a little over a year after September 11th, 2001. In the issue prior to her debut (issue # 132), Morrison writes a tribute to the victims of Genosha, a fictional mutant homeland, where 16 million mutants were killed. There were two direct references to September 11th used in Marvel’s advertising of the comic book, calling the Genosha tragedy “the X-Men’s own 9/11.” The final page of the comic book shows the X-Men team crying at their loss. Next month, in issue # 133, we open to a full page of Wolverine slaughtering Taliban militants.

Maybe I missed something, but the last time I checked, super-heroes don’t kill their enemies, no matter how destructive or deadly. I suppose Muslim radicals are exceptions! Even worse, we see Pakistani terrorists hijacking an Air-India plane while Professor Xavier and Jean Grey are aboard. Xavier uses his psychic abilities to convince the Pakistani hijacker, whose name happens to be Muhammad, to put down his weapon and surrender to the Indian authorities. Muhammad begins to cry and as he is arrested, he says, “It’s true, I don’t know what I’m doing with my life!” Morrison takes revenge on Muslim extremists by (1) brutally slaughtering them (via Wolverine) and (2) passively using mind tricks on them (via Xavier), and the best part is that he gets to (3) rescue an “oppressed” Afghan Muslim adolescent girl and take her home (via Wolverine again)!

Well, almost “home.” Wolverine carries Dust back to an X-Men headquarters in India – no X-Men headquarters in Muslim countries like Afghanistan and Pakistan, I take it – where Jean Grey kindly encourages Dust to reveal herself from concealment. “It’s ok, Sooraya

,” Jean says, “You can turn back into human form now.” Finally, Dust appears in her black burqa saying “Toorab! Toorab!” Wolverine remarks, “It means ‘dust.’ It’s all she says.” Wow, the Arabic word for dust, “toorab,” is all she says? How cute! Not only does Morrison introduce us to a super-powered Muslim girl, but also to somewhat of a doll that exclaims “Toorab! Toorab!” whenever she gets excited about transforming back into human form. I can just picture Wolverine’s conversation with her while flying to India: “So kid, what’s your story?” “Toorab! Toorab!” By the way, shouldn’t she be speaking Farsi or Pashto, since she is Afghan, not Arab?

We not only see a political slant here, which in turn justifies the western male gaze, we also see a female Muslim character that doesn’t have much of a personality. Morrison doesn’t even return to her character after this issue; instead he hands her over to other writers, but perhaps for the better, since they make significant improvements (which I will discuss later). Another thing is in play here and that’s male dependency, something that I discussed in a previous essay of mine, “The Objectification of Women in Graphic Novels.” Although one could argue that Wolverine is practically an indestructible character with his adamantium skeleton and rapid healing factor, it’s hard to believe why Dust would need any rescuing, considering her superpowers and her human enemies. If she was being recruited, the situation would be different and we wouldn’t see any sign of male dependency, but since we see a man rescue her, we assume that Dust’s superpowers are inferior: she is not nearly as powerful as male characters like Wolverine. We have seen female characters rely on their male counterparts in comic books many times before: Super Girl, Bat Girl, Spider Girl, the Huntress, She Hulk, Lois Lane, and so on.

What’s important to look at here is that there is not a single positive male Muslim character in Dust’s debut issue – there are the Taliban militants that want to molest her and there are the Pakistani hijackers – but the Muslim women, who Morrison couldn’t possibly kill off since they’re “victims” in the Muslim world, are innocent, good, and “crying for freedom,” therefore they must be “saved” by western men. The racism and sexism work hand-in-hand.

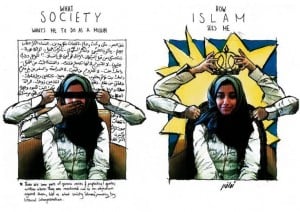

Dust would not make her next appearance until January 2005 in New X-Men: Academy X # 2, where she is officially a member of the mutant team. This time under the authorship of Nunzio DeFilippis and his wife Christina Weir, Dust is explored more and begins to develop into a three-dimensional character. However, stereotypes about Muslim women arise, as does the great Islamic dress code debate. The topic on hijaabs, niqaabs, and burqas is not only controversial among Muslims and non-Muslims, but also among Muslims themselves! Perhaps, it would be no exaggeration to say that this issue is more debated within the Muslim community than outside. In any case, I understand the sensitivity of this matter, so I will offer a hopefully balanced perspective.

Dust would not make her next appearance until January 2005 in New X-Men: Academy X # 2, where she is officially a member of the mutant team. This time under the authorship of Nunzio DeFilippis and his wife Christina Weir, Dust is explored more and begins to develop into a three-dimensional character. However, stereotypes about Muslim women arise, as does the great Islamic dress code debate. The topic on hijaabs, niqaabs, and burqas is not only controversial among Muslims and non-Muslims, but also among Muslims themselves! Perhaps, it would be no exaggeration to say that this issue is more debated within the Muslim community than outside. In any case, I understand the sensitivity of this matter, so I will offer a hopefully balanced perspective.

In issue # 2, Dust meets her roommate, Surge, who wears a tight tank top and pink shorts that are seemingly slipping down her waist. Provocative lyrics play from her boom box: “Yeah I drive naked through the park, and run the stop sign in the dark…” Surge is immediately hostile towards Dust because of the way she dresses. “So you don’t like my music, huh?” she says. Dust responds shyly and explains she doesn’t understand American music. Surge replies, “Yeah whatever, and speaking of things we don’t understand, is that outfit you’re wearing actually a burqa?” Dust tries to explain, but Surge interrupts and says wearing a burqa is shameful to women and makes them “subservient to men.” Dust replies politely, “No, the burqa is about modesty. There are boys and men on campus, and it is not right for me to show off by exposing myself or flesh to them.” Surge snaps back, “Are you saying I show too much flesh?” Again, Dust politely tries to explain, “No, I do not judge the way you dress, I only ask that you do the same for me.” Surge walks to the door and says, “You do judge me… I don’t need to be lectured by someone who’s setting women back fifty years just by walking around like that.” Surge leaves the room and slams the door, leaving Dust dejected and discouraged.

No matter what your stance is on the burqa or the headscarf (hijaab), it is clear that this scene puts Dust on the defensive. In a place where mutants are supposed to feel accepted, Dust is misjudged because of her dress choices. In later issues, particularly New X-Men: Hellions # 2, we learn, from a conversation with her mother, that Dust is not forced to wear the burqa and she enjoys the protection it gives her from men. For Dust, the burqa is a choice, and that must be respected and defended.

However, I believe Dust’s reasoning for wearing the burqa is somewhat inaccurate and stereotypical. This may be due to the writers’ apparent misunderstanding of Muslim women and Islam in general. What’s annoying and arguably inaccurate is how Dust speaks about “protecting herself from men,” which not only make men out to be lustful and perverted, but it also sexualizes herself and makes her an object of desire. The teachings of modesty for both genders in Islam tend to be mistaken for the stereotypical notion of “protecting women from men.” These beliefs keep her side-lined, while the rest of the young Mutants develop crushes on one another and participate in extra-curricular activities. I’m not suggesting that Dust should start dating, but she should at least have some hobbies, otherwise she’s just a one-dimensional character! We either see Dust in the background or we catch a brief scene of her telling a fellow male mutant that she must decline taking a flight with him. It seems like she can’t do anything because her religion is so “restrictive.”

The way the writers present Islam is also a bit irritating. Almost every time we see

Dust, she is praying and asking God for forgiveness for whatever sin she may have committed. A common stereotype that prevails in the west about Islam is that it doesn’t promote “freedom.” The word “Islam” means “submission” and this term is often associated with “slavery.” But Islam is not slavery – to be a servant of God, as believed by Muslims, is seen as humility and liberation of the Soul. It is to acknowledge a higher power greater than them. Unfortunately, Dust fulfills the negative stereotype that Islam is restrictive and that Allah is someone to constantly ask forgiveness from. I doubt these were the intentions of the writers, but it doesn’t take much to pick up on how secluded Dust is most of the time from her peers. It’s as if her social contact and interactions with the opposite sex is something she finds sinful, which is why she must be praying for “forgiveness.” It makes the reader perceive her as a “religious nut” as Surge calls her at one point. It makes me wonder what Dust enjoys doing on her free time? Who does she sit with during school assemblies? Who sits at her table during lunch breaks? These unanswered questions keep Dust’s character incomplete.

I know Muslim women who wear hijaab, niqaab, and even the burqa, and they still have social interactions with men. Since no Muslim alternative is presented, the writers risk Dust being stereotyped and generalized as what all Muslim women are like. It also formulates the stereotype that all Muslim women dress the way she does. There are some Muslims who praise Dust for being a devout Muslim girl who practices Islam “properly” because of the way she observes the burqa, but to praise Dust as a practicing Muslim on the basis of her burqa alone would be a serious mistake. It is also extremely offensive and even insulting because it marginalizes the Muslim women who don’t wear hijaab or the burqa. It assumes that they’re not practicing Islam “properly” just because they don’t share the same views as other Muslims do about dress choices. It creates a wild generalization that only Muslim women dressed in the burqa are spiritual, God-conscious, or practicing Muslims. Anyone familiar with Islamic teachings knows that the inward state of a human being is known to God alone, and just because someone wears a scarf over their head doesn’t immediately make them a pious person. Is Dust a devout Muslim? Yes. Is it because of her burqa? No. Dust states very clearly that she accepts other girls for the way they dress, and she only asks to be accepted for who she is in return. Perhaps we all can learn from Dust and learn how to accept one another for our differences.

So overall, can we appreciate a character like Dust? I think we can; however, there is a lot of room for improvement. As mentioned above, her character is incomplete and her character suffers from stereotypes that are due to misunderstandings about Islamic beliefs and practices. It bothers me that Dust is the product of a post-9/11 storyline, which features stereotypes towards Muslims, in the same way it bothers me that Wonder Woman is the product of a male fantasy. It also bothers me how weak her character is at times. In one scene, Dust loses her burqa after transforming back into human form. She is naked behind the bushes and asks Surge to hand her the burqa. This is insulting and serves no purpose at all except to weaken Dust’s character and to generate western pity for her: the poor Muslim girl who needs her burqa, otherwise she can’t go outside. How come none of the other characters lose their clothes, especially the female characters wearing short tank tops and shorts (or underwear for some)? They won’t lose their clothing, but a girl in a burqa will? Please. Surge then asks Dust what’s the big deal in men looking at her. “They’re just looking, so let them look,” says Surge. Dust, as usual, has weak comebacks and simply says Surge will not understand her. Again, I find this insulting because the writers use Surge to try to cheapen Dust and her personal beliefs. It would be nice to see Dust take a stronger stand for herself and not be so excluded because of her religion. It would also be nice to see more Muslim female characters that help shatter the stereotypes that have been generated about Muslim women. Possible ideas for female Muslim characters could include those who wear hijaab, don’t wear hijaab, and even those who are Shia or Sufi. After all, Islam celebrates diversity and embraces people of all ethnicities, cultures, genders, and schools of thought.

The concept of a female Muslim super-heroine in the realm of comic books is very exciting, but considering the role that women already suffer in comic books, we can expect that the road for characters like Dust won’t be steady. On one hand, she is applauded by a certain portion of readers, including some from the Muslim community, but perhaps, for the wrong reasons, while on the other hand, she is criticized for being too weak, one-dimensional, and stereotypical. There is potential for her to break boundaries, but there are risks and challenges involved: Right now, she is a supporting character in the “Young X-Men” series; is the west ready to see Dust with a comic book of her own? If so, what political stance will writers take on Dust’s religion, culture, and home country? Will artists depict her without the burqa? Will new Muslim characters be introduced to accompany her? Only time will tell. Hopefully, we will see more stories that carry the spirit of the X-Men films rather than those that reinforce old stereotypes.

In Part 2, I will look at how Muslim women are depicted in comic books published in the Arab and Muslim world. So until then: To Be Continued!