In our roundtable on the Foreign Policy “sex issue” I spoke about the responsibility one has when representing, speaking or acting on behalf of one’s own community. Among other reactions to that issue, Mona Eltahawy’s article garnered various responses from Arab women, expressing their disapproval of Eltahawy’s claim to speak on behalf of Arab women. Wherever one stands, I think the issue does raise questions on what it means for Muslims, or those who identify as being in connection with certain countries and cultures, to be speaking on behalf of other women from similar backgrounds. To be honest, I admit that I think it is something that we as writers here on Muslimah Media Watch also have to take into consideration.

For myself, I am a revert to Islam whose Jamaican background does not endure the same racialization of Arab or South Asian Muslims. My ethnicity is not subjected to Orientalist discourses, but instead comes up against racist ideologies that stem from slavery, were entrenched during colonialism, and are continuously perpetuated in imperial and capitalist systems. Not to mention (*trigger warning*) the racial outcry that occurred late last week in Sweden, which happened because of a cake sculpted as a hypersexualized black woman that was created by a black male artist, supposedly making a statement about FGM. I don’t say this as a means of creating a hierarchy of oppression, but as a means of explaining the different struggles my community endures.

So as I read Foreign Policy’s “sex issue,” it tied into my thoughts on Swedish artist of African descent Makode Linde, and on how people have a responsibility to be cautious of how their words, art, and actions make an impact on the communities that they wish to defend.

I want to discuss what responsibility an individual from a broader ethnic, national or religious community has in preventing themselves from falling into the same stereotypes and ideas that have been defined and incorporated into the mainstream’s understanding of Muslims and the Arab world, especially when talking about the realities of the pitfalls or problems within their communities and/or countries, and using their position of privilege to amplify the voices of others who are often forgotten.

Acknowledging Privilege

As writers (and I include myself here), it is important that we acknowledge the privileges we have. These privileges that some of us have including access to an education, living in the West (some, not all), and even have the ability to use resources such as the internet or a computer, are not reflective of our intelligence or the value of our voices. There are circumstances that have allowed some voices and perspectives to be heard over others. What responsibility do we have as Muslim women to use various platforms to discuss these issues? What responsibility do we have to we have to the women who are usually are either at the forefront of activist movements (Eltahawy points to Salwa el-Hussein, Samira Ibrahim, and Rasha Abdel Rahman) or those who often undergo the most traumatic cases of sexual and physical violence but don’t always have access to international media or blogs? Generally, some writers tend to talk about Muslim women living in the Middle East as if they are in a deep slumber, waiting to be awoken. But although another article within the same FP issue opens with a statement from an Afghan woman who says, “Please don’t see us as victims, but look at us as the leaders we are,” all of the writers fail to bring sufficient attention to the historical resistance of women in the region. Instead of providing a space for women who are at the front lines to tell their own stories, Foreign Policy’s sex issue, and in many ways, myself in writing this article, is engaging in dialogue over issues without the most important voices, those who experience first-hand oppression.

How can we open space for women in the Arab and broader Muslim world to tell their own stories? How can we begin to stop the war waged against the bodies of Muslim and brown women without reproducing such practices? How can we respect a woman’s choice, experience and beliefs, without speaking about her as if she doesn’t know any better?

It is important for those of us who are caught up in academia, activist circles, religious scholarship, etc. to really ask ourselves these questions.

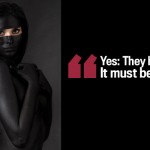

Foreign Policy’s issue was definitely offensive in many ways. From the exotified and sexualized image of a woman in nude painted in black to represent niqab (the veiling that covers all but the eyes) to the content of the publication, Orientalist and other harmful ideologies were highlighted. However, Middle Eastern and Muslim writers were integral to the issue’s (re)production of stereotypical and offensive imagery. In other words, Arab and Muslim writers should be held responsible for their cooperation in nurturing harmful depictions of their communities in mainstream intellectual and media circuits. Thus, it is essential for those of us who want to discuss these issues to pay attention to how we frame and contextualize issues in order to make a conscious effort to say what must be said, but without falling into defining our communities the way the mainstream wants us to; as barbaric, backwards and evil.

It is integral to for us to engage in this dialogue both internally and externally if we are to make meaningful progress in empowering women from all spheres of life, and dare I say, on their own terms.

Bras and Niqabs: Apparently an Odd Mix

A couple weeks ago, Sooraya Graham, 24, a Muslim student in British Columbia, received some backlash from other members of her university. The photography student had a photo of her friend in niqab holding a bra, a means of demonstrating that Muslim women, even those that are veiled, lead very similar lives to their non-Muslim or non-veiled counterparts.

Her photo was quickly taken down from its public location, which was displayed after the image was presented as an assignment for class. A woman who has been identified as an individual who wears the headscarf admitted that she had taken down the image.

Later on, it was discovered that the woman who removed the photo had done so on account of some non-fine arts students who were offended by the image. An article in the Toronto Star states that, “Graham said her intention had been to “humanize” women who wear the niqab, which covers a woman’s entire head except for her eyes, by showing one doing a simple act that many women can relate to.”

Where does the responsibility lie? How far is too far when exercising artistic expression and freedom of speech, and intellectual debate when addressing controversial issues? Sooraya Graham’s photo manages to develop a counter-narrative, or an alternative story, to the depiction of the Muslim women, while confronting the prevailing discourse that women are oppressed. Graham acknowledges through her art work that there are certain problems that women who wear the niqab experience, yet she challenges the reasons and justifications for this experience. Her piece is an example of how Muslim women can tell the stories of their own communities. I believe that the picture sparks debate in a healthy and constructive way. The supposed juxtaposition of a woman in niqab holding a bra forces people to question themselves on why they think the image is peculiar. Do the non-Muslim segments of society feel that Muslim women don’t take advantage of “support,” so to speak? And on the flip-side, have Muslims become too tense to talk about issues that are taboo or seem to deviate from ideas of modesty? Graham’’s photo and the articles written by Arab and Muslim writers in FP grapple with the same tensions.

If we, as Muslims, were to take a flashback to the past to the time of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), we would realize that talking about sexual health, practices and upkeep were not topics that were kept in closets, or left to big elephants to fill. A famous hadith quotes the Prophet as saying, with regards to the openness of the women of Medina to asking about sex-related issues, “Blessed are the women of the Ansar. Shyness did not stand in their way of seeking knowledge about their religion.” It was a conversation that can be held, and has been held, with care, sensitivity, and honesty.

Graham’s picture provided an opportunity, through the use of art, to begin the conversation on how to engage in productive dialogue around topics that seem to be taboo. However, it is worth noting that such an image could have had a violent impact on others in the space. So where is the balance? Did Graham have a responsibility to provide detail of what the intention or message of her photograph?

I think what separates Graham’s work and that produced by the writers of Foreign Policy is audience. Unlike Foreign Policy, Graham’s artwork was created for an educational setting that fosters various perspectives. Foreign Policy, on the other hand, is a publication that is laced with U.S. Nationalism and patriotism. Writing for such a publication comes with the expectation that the audience would be interested in hearing about how magnificent the United States is, and what is doing in its foreign policy to spread the “good ole American dream.”

Lest we fall into the pit of self-loathing, as a result from having the portrayal of our people constantly fed to us to the point that we almost believe it, we need be able to honestly reflect on the reasons why we do what we do and say what we say. The order of the day on Sharrae’s menu is simply, self-reflection. I would be interested to know what MMW readers and other writers think.

Signing off with sincere love.