This post was originally published at wood turtle.

Goggles and gears, corsets adorned with brass and lace brocade, Victorian aesthetics meshed with clockwork, artisans selling creative curios, side show fancies and handmade wares — all came together seamlessly for an imagined moment in time that transformed the historic Gladstone Hotel in Toronto for an annual steampunk street festival.

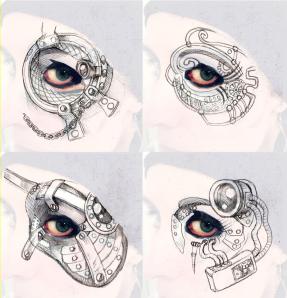

With my feathered top hat pinned firmly to my hijab and my robotic “ocular enhancement” painted on my face, I joined hundreds of other diverse hobbyists who have taken this sub-genre of science fiction beyond imagination and into the reality of fashion, music, performance art, design, philosophy and lifestyle.

I’m fairly new to the steampunk scene in Toronto — and even though I’ve appreciated the culture for years (decades? centuries?) and take any opportunity I can get to dress up in my collection of steampunk gear — this was the first time I’ve actively attended a public event instead of just shyly looking from afar at convention centres.

Recently I’ve decided to become more involved in the steampunk community and was encouraged by a good friend and talented graphic designer who helped create a part of my character. I don’t have the artisan skill to work with metal and leather — but as you know, I’m crafty and enjoy expressing my artistic side with more fluid mediums *cough* like eyeliner.

The girls were decked out in their goggles and held on tight as they took in the fantastical and carefully choreographed event pulled together by Adam Smith, director of Canadian Steam Productions. Soon the dulcet tones of Sir Alfred E Tennyson, Scholar and Gentlemanly DJ, enthusiastically welcomed the crowd, delighted our oratory senses and welcomed an array of steam-inspired entertainment.

While it’s difficult to define exactly what it means for something to be “steampunk,” it’s generally understood to be rooted in an alternative history (or historical future) where steam-power rules and aesthetics are largely influenced by the Victorian period to the mid-20th century. In terms of attitude, steampunk rests on a world of possibility, futurism, but also romantic idealism of the past — and criticisms of the subculture often highlight negative elements that include Empire-worship, the colonial spirit (colonizing other worlds, at least), and overlooking the child labour, rampant disease, institutionalized slavery and racism of the Victorian period.

Since many modern, negative stereotypes about Muslims — as the exotic, savage, sexualized, Orientalized “other” — originate from the Victorian era, what would Muslim Steampunk actually look like? Would it draw specifically from prejudiced Victorian sensibilities, or focus on the strengths and glory of Islam’s Golden Age?

According to Yakoub Islam’s conception — it could be a fantastical world where steam power had been invented in Middle East during the 12th century:

Given how Islam and the Middle Ages are seen by many non-Muslims, it’s understandable that Muslim Steampunk might conjure up mirages of turbans, scimitars (they weren’t around in the mid-twelfth century, by the way), and camel trains undulating slowly through the sun-baked desert. It hasn’t been particularly hard for my hope2be novel, The Muslim Age of Steam, to challenge these well-worn cultural stereotypes.

And in his “cyberpunk” science fiction novel, When Gravity Fails, author George Alec Effinger imagined a world where Arab and Muslim lands ascend while Western and Eurocentric countries “squabble among themselves for remnants of former glory.” The novel’s protagonist is from an unnamed city in the Maghreb and struggles against cybernetic manipulation in a world of corruption that relies heavily on Islamic ritual and modes of conduct.

The brilliant G. Willow Wilson also explores “cyberpunk” in her fabulous, and highly recommended novel Alif the Unseen — where Muslim-inspired Jinn transcend physical and digital boundaries, and “state censorship threatens the online freedom for clients across the Islamic world.”

So steampunk (and “cyberpunk”) is a largely a culture based more on the “realm of the possible” than on a set of ideological rules and regulations and wouldn’t necessarily conflict with Islamic or Muslim sensibilities. So why not imagine an Airship adorned with minarets flying over the pyramids, ferocious Muslimah pirates skimming the seven seas, or an Ottoman Empire protected by an army of clockwork automaton robots?

Doesn’t that mean commodifying a religious symbol and exotifying Muslim cultures?

It’s complicated enough to juggle issues of power, representation and creative expression — but in a fantastical world based on subversion, historical revisionism and the creation of imagined spaces where anything is possible, what boundaries are left to ensure that something remains a respectful tribute and doesn’t become cultural or religious exploitation? What happens when you take symbols, clothes, and religious items, remove them from their specific cultural context and situate them within an imagined world? It might seem cool to “play Arab” and adorn a jambiya with metal gears — but doing so doesn’t make it right, or even “steampunk.”

Jaymee Goh raises this point in her fabulous article On Race and Steampunk: A Quick Primer:

If a visible minority dresses in high Victorian fashion, inspired or derived from English or American sources, is it a sign of overcoming the ills of the time period? Owning the fashion of the oppressors? Or is it a form of assimilation into the dominant culture? If a visible minority creates a steampunk persona based on his or her heritage, is s/he bucking the overwhelming Victorian trend? Exoticising themselves?

When I dress up in high Victorian or Western-steampunk I wear hijab because of my religious obligations and not because I’m trying to create a specific “Muslim Steampunk” aesthetic. The beauty of steampunk is that it’s open to interpretation and aims to combine different elements in new and surprising ways. But my cosplay isn’t about pretending to be an 18th century European who spent time in the “Orient” writing a travelogue, collecting harem pants and bejeweled turbans to incorporate with her bustles and high-collared corsets. It’s more about having an outlet to express my creativity through an aesthetic that speaks to me because of my interests in science fiction and background in western culture.

And I have a thing for automaton robots.

While cultural exchanges within steampunk do not necessarily create a new narrative redefining history, the potential of a re-imagined world where anything is possible is that stereotypes can be challenged, and appreciation of shared cultures can be attempted without intentionally co-opting, commodifying, exotifying, or done at the expense of negatively stereotyping borrowed cultural elements.

And this isn’t limited to the creation of a “Muslim Steampunk.” Stereotypes based on gender, age, sexuality and cultures are all open to reinterpretation within these imagined spaces. Multicultural steampunk has a huge influence in the online community and is championed by brilliant bloggers and academics who explore issues of post-colonialism, assimilation, cultural intersections and the existence of non-Victorian steampunk.

What I really found interesting at the Steam on Queen event was the storytelling. I heard tales of love and danger, sideshow feats of amazement and travels across continents resulting in self discovery. These were not fictional stories — but tales from steampunks themselves, expressing how they personally came to be involved in the culture. Each story was rooted in historical reality — one that would not necessarily be found in the mainstream.

Communities online and in real life are opening up spaces where the issues of the past are being reevaluated and where the exchange of stories can occur. Perhaps as even more people become involved with multicultural steampunk at conventions and more examples of Muslim cyber- and steampunk literature enter the mainstream it will also open opportunities for dialogue.

In the imagined future of steampunk, cultural and social exchange happens for the enhancement and betterment of humanity. As long as cultural exchanges are informed by evaluating privilege and listening to marginalized voices, steampunk has the potential to share obscured stories and perhaps even break down stereotypes.