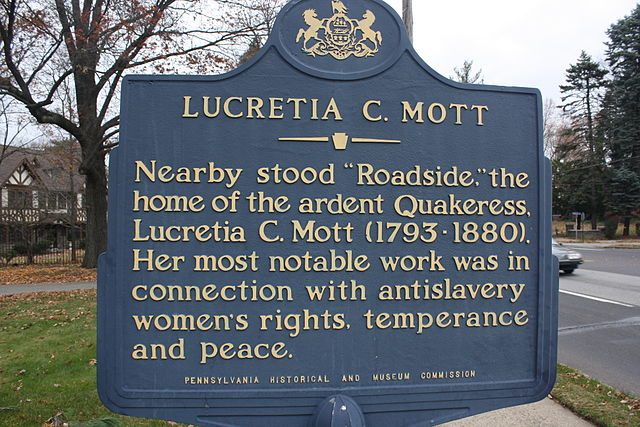

Lucretia Mott is the second in the series of Great Quaker Women. She was a legend in her own time. Her obituary in the New York Times stated that her name was “probably as widely known as that of any other public woman in this or the preceding generation.” She died on November 12, 1880. Mott fought for temperance, women’s rights and the abolition of slavery.

Lucretia Mott is the second in the series of Great Quaker Women. She was a legend in her own time. Her obituary in the New York Times stated that her name was “probably as widely known as that of any other public woman in this or the preceding generation.” She died on November 12, 1880. Mott fought for temperance, women’s rights and the abolition of slavery.

Early Life

Mott was born January 3, 1793 into the long standing and mostly Tory, Quaker family, the Coffins, on Nantucket Island off the coast of Massachusetts. She was well educated near Boston and in Quaker boarding school in Dutchess County, New York where she was a teacher for two years. In 1809, she joined her family in Philadelphia. She said, “I grew up so thoroughly imbued with women’s rights that it was the most important question of my life from a very early day.”

A fellow teacher also moved to Philadelphia. Lucretia Coffin married James Mott in 1811 at the age of 19. They had six children, 5 surviving to adulthood. By 1818 after losing a son aged 5, she became more involved in Quaker affairs. She also began to preach throughout the mid-Atlantic states, often accompanied by James.

Beliefs into Action

Lucretia Coffin Mott was steadfast in her Quaker beliefs. She worked for social goals that seem now to naturally follow Quaker testimonies: abolition and women’s right. In 1827 when the great division of Quaker occurred, the Motts went with the more progressive Hicksites instead of the more orthodox, evangelical branch of Friends.

The Motts eschewed all slave produced products and considered slaveholding to be an evil. They often sheltered runaway slaves in their home. Mott became clerk of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting in 1830. She was one of the founders of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1833. When the American Anti-Slavery Society admitted women, she joined that, too.

Women’s Equality

Because she was a woman, Mott was denied entrance at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in 1840 in London. She stayed outside the conference hall and preached about female equality. During her London visit, she met Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Eight years later in the summer of 1848, they organized the momentous Seneca Falls Convention and launched the American women’s rights movement. Mott published her Discourse on Women in 1850.

Mott preached non-violence and spoke against the Civil War. Following the war, she worked for black suffrage and women’s suffrage. She helped to found Swarthmore College outside of Philadelphia in 1864. It remains a coeducational institution to this day.

When the women’s movement split over whether to seek the suffrage of freedmen and women or freedmen first, she tried to heal the rift. She continued her efforts for the disempowered until she died. She gave her last speech in 1878 at the 30th celebration of the Seneca Falls Convention. Mott died near Philadelphia in 1880 twelve years after her husband.

In 1879, she wrote, “In a true marriage relationship, the independence of husband and of wife is equal, their dependence mutual, and their obligations reciprocal.”

photo: Wikipedia Commons