We’ve got five years, what a surprise

Five years, stuck on my eyes

We’ve got five years, my brain hurts a lot

Five years, that’s all we’ve got

– David Bowie.

It was five years ago this past weekend that the world mourned the loss of iconic rock star David Bowie. Two days after Bowie’s 69th birthday, and the release of his final album, the masterpiece “Blackstar,” which in retrospect was the artist’s own requiem, Bowie succumbed to the liver cancer that so few people had known was afflicting him.

For me, as a musician, occultist, and performance scholar, who had grown up with Bowie’s music, whose formative years were immeasurably influenced by the Bowie persona itself, the loss was devastating.

Five years later, much of Bowie’s life as a musician, artist, and erstwhile occultist, remains a mystery to me. The fact that he would have such an impact on the culture of Western music and stardom, seems so unlikely, given how he didn’t conform to most trends and maintained his iconoclastic place in cultural (and occultural) history across his roughly 55 year career.

Yet, I can’t think of a better representation of both the fascinating power and the tense anxieties behind the alchemical mixture of music, performance and the occult.

Over the weekend, I paid tribute to Bowie by re-watching his bizarre, confusing 1976 film debut, Nicholas Roeg’s “The Man Who Fell to Earth,” based on the 1963 novel by Walter Tevis. I had watched it once long ago in college in the early 90s, but I basically had forgotten the whole thing. Of course, I was struck by how utterly weird the film is, even by today’s standards, but also by the way the film constantly jumps ahead in time with no warning and suddenly, supporting actors like Buck Henry, Rip Torn and Candy Clark are visibly much older, while Bowie’s earthbound Thomas Jerome Newton remains ageless and unchanged.

Perhaps not unintentionally so, these unexplained time jumps reminded me of the final scenes of Dave Bowman in “2001: A Space Odyssey,” a film that inspired Bowie to pen his first major hit. But it also solidified that Bowie, as a persona, as a mysterious force, is eternal.

When I look back to my own childhood encounters with Bowie, it is this same time period (roughly 1976-78) that holds my imagination the most. At that point, I was certainly familiar with the famous singles, such as “Changes” and “Fame,” from radio play, and “Space Oddity” certainly was an obsession of mine, as were all things space and science fiction (just a year or two prior to “Star Wars”). My older brother had a copy of the “Changes One” singles compilation, so that was the start.

When I locate my music fandom as a child and later pre-teen, I was surrounded by the influences of a family friend and neighbor who would bring over import records. We reveled in (mostly) British and German music, early ska and what would later be called post-punk. But the music that captured my imagination the most was the electronic music. Kraftwerk, DEVO, Gary Numan, then later in the early 80s, Thomas Dolby, Depeche Mode, Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark.

And while it’s odd to think that a 7 year old would be knowledgeable about the early wave of electronic music, that was the air I breathed. I constantly snuck into my older brother’s room while he was still at football practice, to listen to those albums and live in that world that spoke to my alienation, that sense that I wasn’t like the other young boys in Northeast Ohio where I grew up, obsessed with sports and testosterone filled classic rock. And Bowie was at the forefront of my world.

Of the Bowie albums I had access to, the two that I listened to the most were Bowie’s classic “The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars” (1972) and “Station to Station” (1976). I heard the other albums up until that point, but those two for some reason were quintessential Bowie to me, where I could imagine the worlds that the albums created and escape there in my young mind, despite being utterly oblivious to all the references to sex, drugs, and well, the occult.

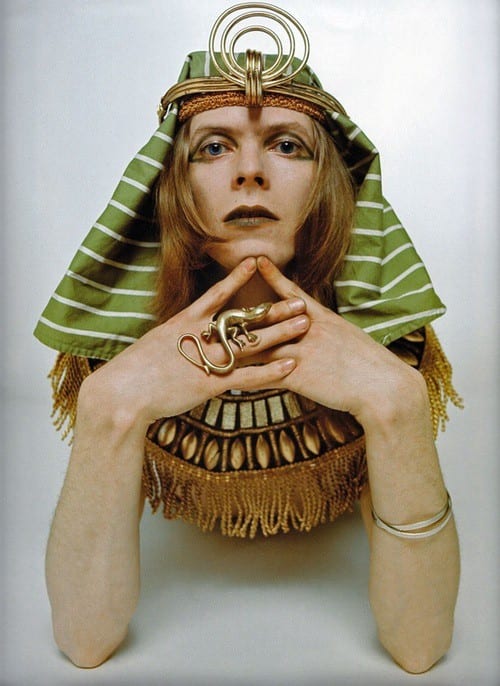

And while I didn’t see much of Bowie on television at that point, the pictures on the records and the inner sleeves captivated me. Similar to the robotic and mannequin-like images of the members of Kraftwerk on their albums, or the otherworldly look of Gary Numan on “Replicas,” my other favorite “sci-fi” album of the time, Bowie’s look spoke to me of mysterious alien power, the ability to create worlds, and the confidence to perform that persona to an audience, and further, to navigate those worlds.

In a sense, Bowie was my first idea of what a musical performer was: androgyny, theatricality and all, even before MTV offered a certain range of those personas. Bowie was the one that always stuck with me, even when I had eventually moved on to Ian Curtis of Joy Division, Peter Murphy of Bauhaus and Morrissey of The Smiths as major influences, especially when I had pretensions of fronting teenage bands.

And I confess, my fandom did eventually slip. “Let’s Dance,” Bowie’s 1983 monster hit album, was the first album (well, cassette) that I owned myself, instead of borrowing from my brother’s collection, and I certainly loved that one, though not as much as those earlier albums. And I remember staying up late to catch the premiere of the short film that was the extended video for “Blue Jean” on “Friday Night Videos” (before my family had cable and MTV). But then I remember being unimpressed with the rest of that album (the lackluster “Tonight”) and, well, pretty much any Bowie single after that. The oversaturation killed it for me.

I had moved on. So much so, that I was only vaguely aware of anything Bowie did after that. Even his somewhat interesting forays into industrial music, including his 1997 collaboration with Trent Reznor, “I’m Afraid of Americans,” which has been shared quite a bit lately on social media lately due to the obvious resonance of its themes in the Trump era, failed to leave an impression.

I never did wind up seeing Bowie in concert, though I’m sure I probably had opportunities. I was just never one to spend insane amounts of money on a large concert where I’d only really be able to see the performer on a giant video screen. Stadium venues were never my thing.

But then my curiosity was piqued when Bowie came back after a decade long absence with “The Next Day” in 2013. I began to re-discover my love for his work and I started to revisit his back catalog, delving into albums that I had somehow never heard before. This included Bowie’s collaborations with Brian Eno, the “Berlin trilogy” of 1977-1979, which made Gary Numan’s arrival a few years later make so much more sense, in retrospect. And then “Blackstar” hit me like a ton of bricks.

“Blackstar” is seven practically perfect art rock experiments, played by jazz musicians. And who knew that a 2016 album would remind me how cool a saxophone still is in rock music? And then there’s the title track, the 10 minute opus that occultists have picked apart searching for meaning and correspondences. Is the “solitary candle” in the “Villa of Ormen” an Aleister Crowley reference? Does the title “Blackstar” refer to a cancer lesion, an astronomical event, or some other esoteric principle?

Another trove of clues is the intense, unsettling final two music videos Bowie filmed, “Blackstar” and “Lazarus.” Directed by self-professed Crowley enthusiast Johan Renck, the images are haunting and evocative: crucified, gyrating scarecrows, an alien woman with tail, delicately holding a jewel-encrusted skull found inside an astronaut helmet, convulsing and shaking women in a ritual circle. Bowie, in one of several personas he takes on during the video, holds aloft a little black book with a pentagram on it that some have suggested is an analogue to Crowley’s Book of the Law.

Some have speculated that the skull in the astronaut helmet is, in fact, Major Tom, the main character of Bowie’s first major hit, “Space Oddity,” who Bowie later cast as a junkie in “Ashes to Ashes.” Here, Major Tom, lost in space, has finally transcended into a spiritual being and brought back down to earth.

But the story behind the other video, “Lazarus,” suggests another Tom who was central to the Bowie mythos: Thomas Jerome Newton, the main character Bowie had played in “The Man Who Fell to Earth.” Bowie’s interest in the character returned before the end of his life and just before recording of the “Blackstar” album, he collaborated with Irish playwright Enda Walsh and Belgian director Ivo van Hove on producing the musical, “Lazarus.”

Featuring prominent songs from Bowie’s oeuvre, including “Life on Mars,” “Changes,” and many others, in addition to some of the new material, the play was a retelling of the Newton story, based on the book and the film, but continuing on with new characters, including a teenage “ethereal girl” (who many have noted was the same age as Bowie’s daughter) who tries to help Newton return to his home planet. By no means a clear linear narrative, and just as much a mystery as anything else Bowie produced in terms of how it reflects his life and story, the play was still successful and quite a final statement from the starman. And this past weekend on the anniversary of his death, viewers were treated to some rare live stream performances of the show, making it accessible to more audiences.

With the video for the song “Lazarus,” re-worked from the musical for the “Blackstar” album, Bowie once again plays several personas. He’s the dying, button-eyed man from the “Blackstar” video in the hospital bed, but he also plays a trickster figure, frantically trying to create and come up with new ideas. That trickster is unmistakably dressed in the outfit Bowie wore for the inner sleeve picture of “Station to Station,” that showed him drawing out the Kabbalistic Tree of Life on the floor.

In a 1997 interview, Bowie famously claimed that “Station to Station” was “the nearest album to a magick treatise that I’ve written.” Indeed, like “Blackstar,” occultists have tried to thoroughly unpack the album’s title track, starting with the line “one magical movement from Kether to Malkuth.” When I think of my love for that song as a child, I remember how, before lyric (or any) websites were a thing, most of the time I had no idea what he was saying, to the point that I was unaware of this line until just a few years before he died (though I was definitely able to make out the “side effects of the cocaine” line as a kid).

That magical movement is, in fact, the “lightning flash” that travels through all the spheres of the Tree of the Life, the manifestation of the divine into material being, from Kether, the top sphere closest to the divine, analogous to the crown chakra at the top of our head, to Malkuth, the earthly plane manifested at our feet. Kabbalists often speak of the creative process as bringing ideas inspired by the divine into material being, just as Bowie constantly did, as any artist would do.

Using this tree of life imagery, I think of Major Tom’s journey in “Space Oddity” as crossing the Abyss, the space between the physical manifestations of the sephirot and the supernal triangle of the divine, a journey from which there is no return. Conversely, Thomas Newton’s journey from the stars, falling to earth, is one in which divinity is sacrificed for the physical. And in Newton’s (and for a while, Bowie’s) case, that physical plane is a morass of drugs, addiction, and isolation. In the “Lazarus” video, as Bowie’s button-eyed man remains dying, on the hospital bed, the trickster Bowie retreats haltingly back into the dark closet from which he came.

One of the mysteries of Bowie’s artistic references at the end of his life, then, is why he returns to his particular moment in his career, with the revival of the Thomas Newton character from “The Man Who Fell to Earth” and the visual reference to “Station to Station,” both projects that he completed practically back to back in 1975-1976.

We know from interviews and biographies that this was a particularly dark time in Bowie’s life, living in Los Angeles, with his cocaine addiction, occult interests and paranoid obsession that he was under attack from evil entities. Though Bowie’s interest in occult texts and figures like Crowley, A.E. Waite, Dion Fortune, Israel Regardie, Eliphas Lévi, Edward Bulwer-Lytton is well documented, and he was referencing the Golden Dawn and Crowley himself in early songs like “Quicksand” on “Hunky Dory” (1971), some scholars believe these flirtations were more about referencing the avant-garde cultural milieu that produced Bowie, rather than a genuine dedication to the occult arts. Ethan Doyle White makes such a claim in this fascinating essay, unpacking all of Bowie’s occult associations, including his encounters with the “White Witch” of New York and speculation that he may have crossed paths with Jack Parson’s widow in LA.

Bowie himself tended to downplay and disparage that period in interviews, either joking about his occult obsessions or characterizing this time of his life as drug-addled (though co-star Candy Clark disputes Bowie’s own weak recollection of being wasted on the set of “The Man Who Fell to Earth”). And as anyone who has read more than one Bowie interview knows, he tended to play with interviewers and give teasing answers, determined to forever avoid being pinned down. Speculation about Bowie’s occult dabbling has only grown since his death. I won’t cover all the theories and connections here, but there are many pieces out there that go into more detail, like this one.

But clearly, there was something about this period in his life that Bowie wanted to revisit as he was facing his own mortality. In Peter Bebergal’s fascinating work, “The Season 0f the Witch: How the Occult Saved Rock and Roll” (2014), the author notes that none of Bowie’s varied personas really adopted the role of magus. Rather, they were usually alienated and alien figures. Bebergal argues that the true occult secret of Bowie goes beyond just the references and occultural contexts. Bowie himself demonstrates the principles of magic with his powerful glamour, his ability to “cause change to occur in conformity with will,” and his talent for seducing audiences, as a magus would, with ritual and ceremony. In the end, Bebergal proclaims, “there is likely no truer magician than Bowie.”

Early last year, I had a bizarre dream that David Bowie was leading a parade marching through a town, holding hands with all his fans, including me, and we all were singing the final track on Bowie’s last album, “I Can’t Give Everything Away.” That song in particular always struck me as such a fitting farewell. In one of a series of excellent blog posts that do a deep dive on Bowie’s songs, Chris O’Leary, author of “Ashes to Ashes: The Songs of David Bowie,” describes “I Can’t Give Everything Away” as Bowie’s version of Prospero’s final speech from “The Tempest,” in which the Shakespearian magus pledges to drown his books and renounce magic:

But release me from my bands

With the help of your good hands:

Gentle breath of yours my sails

Must fill, or else my project fails,

Which was to please. Now I want

Spirits to enforce, art to enchant,

And my ending is despair,(15)

Unless I be relieved by prayer,

Which pierces so, that it assaults

Mercy itself, and frees all faults.

As you from crimes would pardoned be,

Let your indulgence set me free.

These mysteries may never be solved, but at the end, we are left with Bowie’s enduring spirit, pleading with us to set it free from any desire to define and categorize it. The magic is still in the experience of the music and the memories of how we’ve encountered it. And ultimately, that was what Major Tom, and Bowie himself, wanted from the beginning, to be free to ascend beyond the stars into the unknown.