In my last post I began to lay out the argument that Judaism appears heading for a Post-Rabbinic form, that a new way of understanding Judaism and being Jewish is emerging and has been, for the past fifty years or so.

Yet what exactly is “Rabbinic” Judaism and what does “Post-Rabbinic” mean?

Rabbinic Judaism

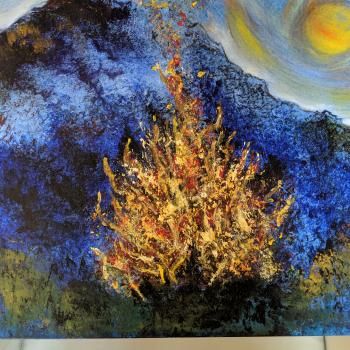

Rabbinic Judaism has been the mainstream form of Judaism since approximately the 6th Century CE. It’s earlier forms emerged with movements such as the Pharisees and those like them in the first centuries of the common era. The early, yet primary, catalysts for Rabbinic Judaism were the Jewish experiences of exile and the destructions of the Temple in Jerusalem – thus eliminating the central religious powers rooted in Temple control and the sacrificial system of worship centered therein.

Rabbinic Judaism is based on the traditional belief that at Mount Sinai, God gave Moses the written Torah in addition to an oral explanation, known as the oral Torah, that was also transmitted to the people. Eventually, the Rabbis emerged to interpret and teach the meaning of these writings, traditions, and commandments.

The Rabbi’s asserted that Torah contained mitzvot, or sacred commandments, that formed the outline of Jewish law and the distinctive way of Jewish life. The Talmud is a centuries long commentary written by various Rabbis on the Torah and its mitzvot, outlining various approaches and meanings to such. The traditional 613 mitzvot roughly correspond to the notion of Halakhah, or Jewish law.

Obeying the mitzvot and performing acts of loving kindness are the new sacrifices of the Jewish people, the new way of atonement, leaving behind burnt lambs, oxen, and cereal offerings.

Today, there are profound differences among the various Jewish denominations within Rabbinic Judaism concerning the binding nature of Halakhah, as well as a growing willingness to challenge or even revise preceding interpretations. Still, nearly all forms of modern Judaism are rooted in the Rabbinic method of analysis and subsequent theology.

Post-Rabbinic Judaism

Some scholars argue that Rabbinic Judaism has already transformed beyond it’s original parameters and therefore, we are in the early stages of a Post-Rabbinic age. Describing the core principles of such a Judaism remains the topic of much conversation and analysis.

There are also arguments that Rabbinic Judaism contains the seeds of its own undoing, primarily in its understanding of Biblical commentary, midrash, and exegesis – an understanding that the sacred writings should be reinterpreted by each generation of Jews, that each Jew has a stake in the ongoing Jewish conversation. Some argue that these approaches lead to subjectivism and the watering down of Jewish tradition.

The most common example of such is how Reform Judaism leaned on these principles of reinterpretation and created a Judaism of the autonomous self, placing the individual Jew at the center of Judaism, thus putting an end to rabbinic power and authority, and replacing rabbinic law and communal obligation with individual choice.

Further, it is important to note, a Post-Rabbinic Judaism would likely apply only within Liberal Jewish circles, the Orthodox remaining firm proponents of their version of Rabbinic Judaism. Many Orthodox Jews currently don’t accept the validity of Liberal Judaism, no less any sense of Post-Rabbinic Judaism.

Still, let us ask what a post-Rabbinic Judaism would look like? I’d argue it would likely include the following central trends:

A Reformulation of Jewish Theology – to a large degree, this has already been happening – the work of Kaplan, Heschel, Green, Borowitz, and others, has laid the foundations for further revisioning of the traditional positions on God, Torah, theological methodology, and Judaism’s role in the modern world.

A Full-Scale Revision (or Jettisoning) of Halakhah – few Liberal Jews are even aware of what constitutes Halakhah and are familiar with only a handful of the 613 traditional commandments. Reform Judaism has already made the observance of these mitzvot optional. Some of the mitzvot are limited to observance in Israel, others seem archaic. Might Halakhah be rewritten? Might some Mitzvot be removed from the “list?” Might the entire category be eliminated altogether?

A Full-Scale Revision of Jewish Liturgy – little of Jewish liturgy has caught up with the changes in theology and understanding. Even the Reform Siddur contains many prayers in their original Hebrew that speak in terms of a classical theism, miracles, and forms of praise and petition many, if not most, now consider relics of a bygone era of faith.

With the work of Marcia Falk, women who have reclaimed Rosh Chodesh with new liturgies, those who have created new seder forms – synagogues and communities that have written their own siddur – there already is much ongoing revision.

Yet there remains a tension – the traditional prayer forms are well-known, loved, and evoke familiarity, nostalgia – many would prefer to leave them, at least in their Hebrew forms, and engage in reinterpretation in their English forms. Yet have even these contemporary translations gone far enough to match today’s theological realities?

Redefining Who is a Jew – again, this has already begun in many Liberal Jewish communities – the acceptance of patrilineal descent in Reform communities, the welcoming of interfaith couples, continued rethinking the conversion process – intermarriage, and so on.

Many would argue that the above is already happening across Liberal Judaism and therefore, Post-Rabbinic Judaism has already been birthed. Others would argue that current changes need to go further.

What does going further mean? What have I left out in terms of the traits and concerns of a Post-Rabbinic Judaism? I’d enjoy hearing your thoughts and ideas.

What’s Next?

As we ponder what’s next, I leave you with the work of Rabbi Rami Shapiro, an advocate and pioneer of developing a Post-Rabbinic Judaism. The below is his blog post on Reimagining Judaism – extremely worthwhile reading.

http://www.rabbirami.com/reimagining-judaism/