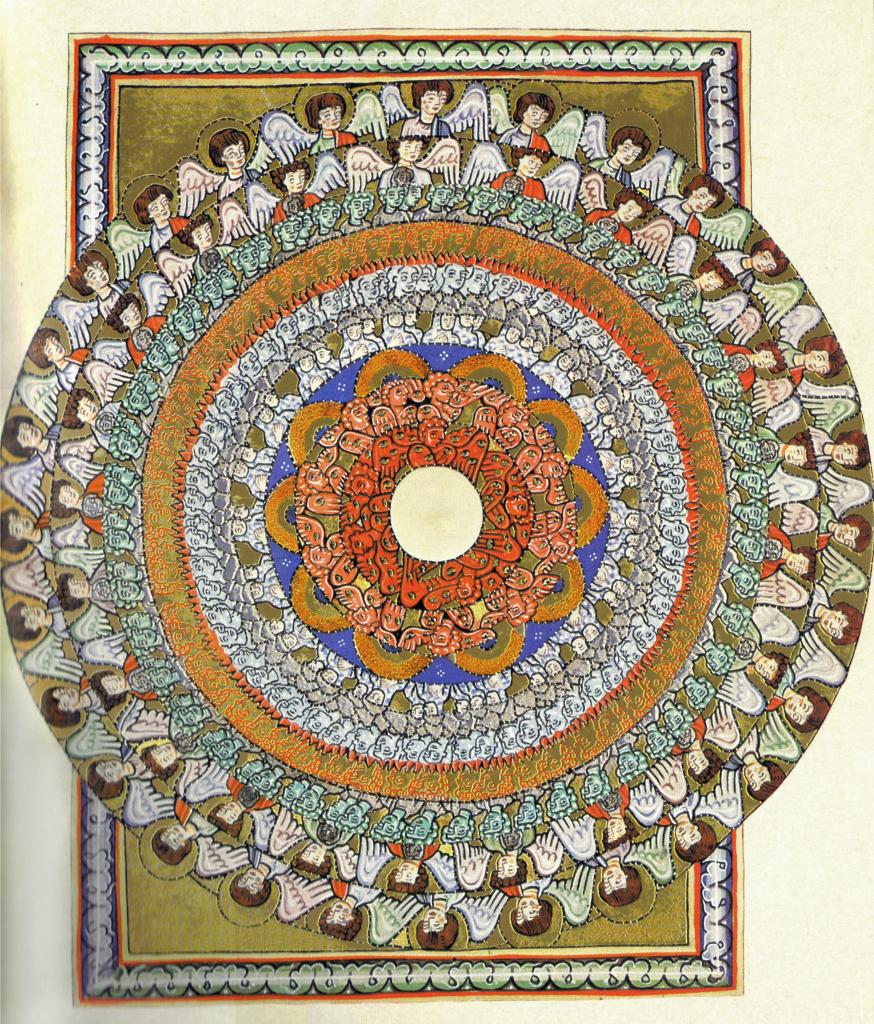

Hildegard of Bingen is, to use one writer’s phrase (William Harmless), a mystical multimedia artist. She wrote, lived, preached and practiced natural healing, composed music, wrote a morality play, ran a convent, and most famously of all, experienced visions. Her main theological works form a trilogy in which she interprets her complex and colorful visions through the lens of Christian theology.

Not only are Hildegard’s visions beautiful, and bizarre, they are actually illustrated, each vision piercing through the page with a picture, followed by Hildegard’s lengthy, unique, and, perhaps surprisingly, deeply orthodox interpretation of what it all means.

Underlying Hildegard’s manifold interests lay political savvy; she negotiated enough power and support from the Pope and the German emperor to pursue her prophetic vocation. She preached to clergy and laity in a time when women did not preach in public. She procured enough trust from the archbishop to start her own independent community of nuns. Hildegard was a fruitful artist, a visionary woman, a prophetess of greenness.

There’s a concept in particular that ebbs and flows throughout Hildegard’s writings: greenness, or, in Latin, viriditas. The word comes from the Latin virido, to make green or to grow green. Hildegard uses this word so much and in such a wide-ranging way that translators don’t know what to do with it. Sometimes they translate it as “green,” but also as freshness, vitality, fecundity, fruitfulness, and growth. And really, it sums up the essence of Hildegard’s theology, because for Hildegard, the whole universe is “green.” It’s alive, ecological, more of a verb than a noun. The whole universe is, as it were, pulsing with divine essence, sustained by Spirit’s evolving life-energy. God and the universe are greening.

Viriditas is both a literal and symbolic concept in Hildegard. It describes the natural world and it traverses theological ground: plants are “green,” fields are “green,” but even inanimate rocks shimmer with the greenness of God’s gift of existence and God animates Adam with greenness and the Incarnation of Christ pours forth through the Holy Spirit’s sweet greenness.

The concept of life in John’s gospel dances in a way similar to how greenness grows in Hildegard. Life, for John, contains many meanings. It’s both physical and symbolic, earthy and ethereal. In Cana, the same site of Jesus’ first water-to-wine sign, a royal official journeys to Jesus. His son lies at the point of death, and Jesus assures the man, “Go, your son will live.” He will have life. Jesus’ ministry in John’s gospel is a life-giving force that makes a paralyzed man walk, gives sight to a blind man, shares bread with five thousand people, and commands life’s emergence even from Lazarus’s tomb of death. The culmination of God’s life in John’s gospel makes itself known especially through the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus.

And like Hildegard, John is eager to emphasize that the sustaining source of physical life is divine life. Material reality is not all there is; matter and spirit coexist because everything that is lives in and because of God.

John’s prologue declares that all things came into being through the Word, and yet the next verse asserts that there’s something more, there’s something vital and essential that animates the world. Hildegard calls it greenness, but John says, what has come into being in him was life, and this life was the light of all people. “I have come,” after all, Jesus says, “that they may have life, and have it abundantly.”

Many post-Christians and progressive Christians have a checkered history, however, with John’s sense of life. If you’re like me, you may have heard John 3:16 wielded as what Brian Mclaren calls “God’s evacuation plan from the world.” Eternal life handed out as a heavenly space ticket out of here, a way of escape earth’s messiness and responsibilities. Why campaign for urgent action on climate change, the evacuation message teaches, because we’re not going to be here long anyway.

But divine life in John, as other-worldly as it sometimes seems, is not later. Eternal is not, as Richard Rohr, says, “chronological moments of endless duration” but it’s “time as momentous and revealing the whole right now.” Or, as one scholar, John Ashton, translates it, eternal life should read “life of the ages.” In John’s imagination, the time of the new age, the moment of God’s life revealed, is today. It’s now. It might be tomorrow, too, but what matters is that God throws open the doors of heaven’s realm in this moment.

Hildegard’s visionary book the Scivias ends with a heavenly choir singing of God’s greenness, and yet heaven is not an angelic chorus running on repeat in the bliss of afterlife. John’s vision, and Hildegard’s, too, is that the fresh abundance of God’s life starts now, and grows in our lives, in our church, in our world, and continues growing all the way to the life to come, to the new transformation of earth and heaven that is at hand.

And yet the struggle of the spiritual journey is that our life energy lags. John, dramatic as usual, would say that many of us are spiritually dead, or at least on the precipice of perishing. Hildegard would put it more ecologically: we’re going through a drought, she might say, or we’re dwelling in a fruitless field, which is the opposite of greenness or viriditas. (There’s a place in her third visionary book “The Divine Works” that contrasts viriditas with ariditas or dryness, drought, aridity).

We are often dry, our souls are desolate, disconnected from divinity, the source of being, the energy of growth. And we all know people, and maybe it’s us, too, who have tragically stopped growing, whose passion has died, whose creativity has become blocked, who have become stuck in deadening habits and trapped in a desert…or to use a New England metaphor, secluded inside a perpetual winter.

Instead of fresh newness, life somehow became one thing after the other, and maybe something excruciatingly painful happened and at first it hurt. But then, our thirst and desire turned in itself and we actually became less alive, less expectant, less hopeful, less willing to try new things, less green. Hildegard’s prayer, and John’s too, is that Spirit bursts forth in our world with a fountain of abundant aliveness.

A green life is a fruitful life. It’s not the fruitfulness of Genesis, the functional command to “be fruitful and multiply,” but, rather, it’s an ecological fruitfulness of soul. Fruitful people effuse fruits of Spirit, which Paul lists in Galatians as love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control. But even these virtues can feel sometimes static, locked in the frame of a heavenly hallmark card.

Hildegard’s genius is to introduce the language of the living natural world into the often fixed corridors of religion, so that God, the world, and humanity are never unchanging, but always emerging, always sprouting seeds of new possibilities, always evolving, always greening.

And as a mystical multi-media artist, Hildegard lived what she wrote. She suffered severe health difficulties for much of her life, and yet she somehow finished her trilogy of visionary works in her mid-70s. Within the structure of a patriarchal church, Hildegard’s prophetic vocation took her on four preaching tours throughout Germany. In an era in which universities reserved the medical profession for men, Hildegard wrote two medical texts filled with holistic wisdom distilled from the natural world, and created an astonishing musical output.

Hildegard points to the possibility of a green life, or better yet, a greening life, a life that does not simply exist, but a life that thrives and flourishes, bountifully. A life attuned to the earth, awakened, and sustained by God.

Photo: Hildegard of Bingen, Angels, public domain