The universe is strange.

Here are a few paraphrased facts from an article I stumbled across: If you unraveled all of the DNA in your body, it would span 34 billion miles, reaching to Pluto and back (2.66 billion miles away)…six times.

Almost all of ordinary matter is empty space. If you took out all of the space in our atoms, the entire human race (all 7 billion of us) would fit inside a sugar cube.

Many of the atoms you’re made of, from the calcium in bones to the iron in blood, were brewed up in the mixture of an exploding star billions of years ago. Almost all of our hydrogen atoms were formed in the Big Bang, about 13.7 billion years ago.

Back in the days before digital television, if you tuned your TV between stations, a small percentage of the static you would see would actually be afterglow from the Big Bang.

The universe is strange. There’s no denying it.

If you take a look around at mainline religion these days, however, it’s not very strange. It’s fairly reasonable.

We affirm what makes sense to us. We ignore the parts that don’t.

Miracles, demons, angels and resurrection make progressive Christians slightly uncomfortable, but we often contextualize those aspects of religion as outdated, as metaphors, or as aspects of crusty old faith that we simply don’t need anymore.

What if faith became strange again, at least as strange as the universe?

To this end, I share a question I’ve been pondering: What if angels really are watching over us?

Or at least, what if angels are a spiritual way of talking about the immense strangeness in the universe?

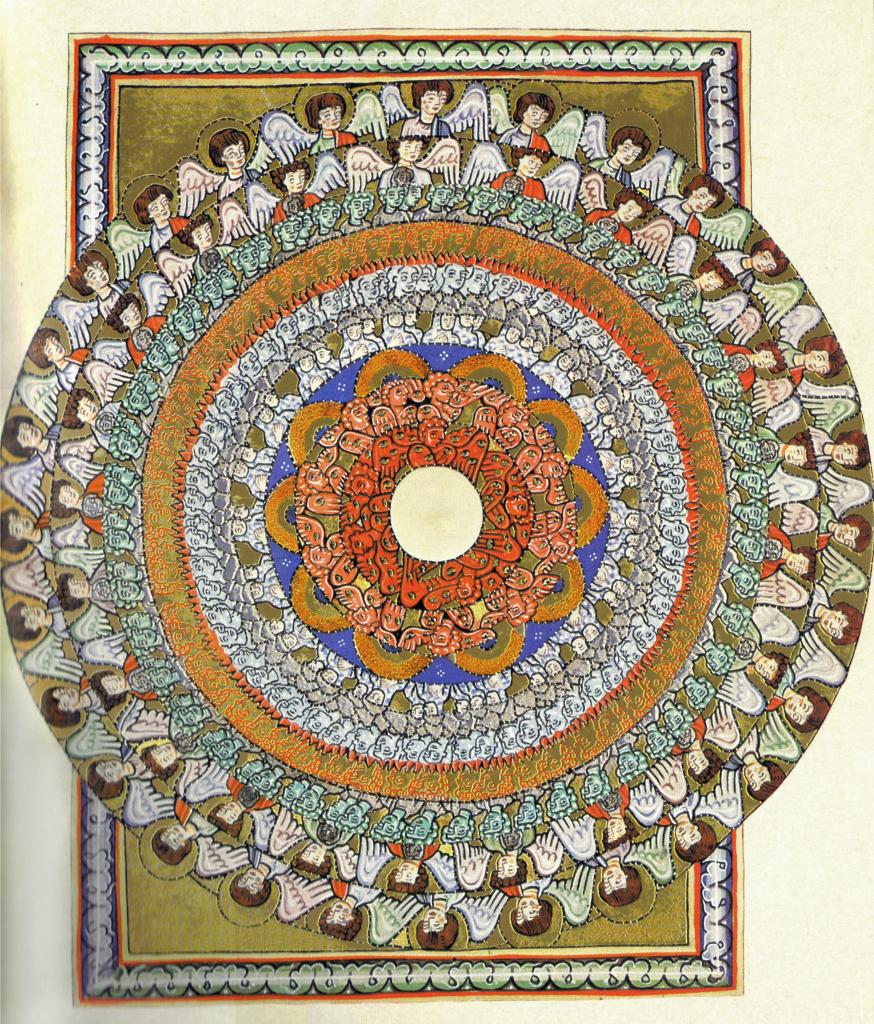

Angels are strange.

Even to speak of angels is, to most of us, strange.

Angels in the Bible, too, are strange. They often turn out to be unfamiliar visitors, from Abraham’s hospitality to the three men in Genesis, to Jacob physically wrestling with an unknown man at the Jabbok Rivers, to those famous heavenly creatures Michael and Gabriel announcing big news for Mary and Joseph and the whole world.

The letter to the Hebrews reminds reader “not to neglect showing hospitality to strangers, for by doing that some have entertained angels unawares.” Angels are messengers, in Greek aggelos, or messenger.

What if these messengers are real in some strange way today, bearing God’s news of love and justice, and telling the truth of who we are?

What if the world is filled with angels?

I don’t mean the winged, friendly creatures made trite by holiday cards and Christmas decorations. I also don’t intend to throw out the good tools of critical reason and instead affirm every fairy-tale and vision of light at the end of the tunnel. If the Biblical account has anything to do with it, we’d most like to avoid facing angels lest they crash into and disrupt our lives, or at least break through the ceiling, as one does at the end of Tony Kushner’s epic play Angels in America.

The Bible simply assumes that we live in a universe in which the veil between heaven and earth is thin, and in which heavenly intermediaries or messengers frequently support the cause.

If you asked an ancient person about how the universe works, they wouldn’t have the tools to tell you much that would hold scientific weight today, but the odds are, they’d bring up angels.

According to the Book of Jubilees (2:2), a book that did not make it into the Bible but which early Christians read, angels are there at the creation of the world. They dwell as personalities over the elements: angels of fire, angels of winds, clouds, darkness, snow, hail, hoar, frost, cold, heat, thunder, lightning, and seasons.

It all sounds very Celtic, doesn’t it? Celtic writer J. Philip Newell prays an angelic prayer, perhaps: the strength of the rising sun, the strength of the swelling sea, the high mountains, the fertile plains, the strength of the everlasting river, the strength of the river of God, flowing in me and through me this day.

Angels are more, though, than mysterious figures that pop up repeatedly in Jacob’s vision of a ladder to heaven, or at Jesus’s empty tomb.

They also symbolize the collective reality of whole peoples.

Check this out: in Deuteronomy chapter 32, the author imagines God dividing up the nations, and each people group is given an angel, what’s translated as a “god.”

In the book of Revelation—that science fiction horror genre mash-up that might just be the most interesting book in the Bible—the prophetic visionary John of Patmos, exiled on an island, writes letters not to leaders of the seven churches but to the seven angels of the seven churches.

What might an angel of an individual church community be like? What joys does she carry, and what wounds? What might the angel of the United States of America, or the angel of the Planet Earth, be telling us?

To take the matter further, what if there is a scientific correspondence to angels?

Charles Darwin did not articulate the theory of natural selection on his own.

A young British naturalist named Alfred Russel Wallace independently came to his own conclusions about evolution and natural selection—right around the same time. Wallace had been in dialogue with Darwin, and—not knowing that Darwin was working on his own book of the topic—sent him an essay all the way from the Indonesian island of Ternate entitled “On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely from the Original Type.”

Folks in this time were generally creationists who believed that God created all different types of individual species from the very beginning. Each species was separate and unique, not interrelated in a web of ever-changing life. To depart from God’s original type with variety, then, was epoch-changing and overturned not only religious dogma of the time, but also scientific beliefs.

Darwin, of course, was startled to discover that Wallace had come to the same conclusion as he had, and rushed to publish his book first.

Can you imagine? Sitting on a paradigm-shattering theory, thinking you are the only one, and then realizing that someone else had discovered it too! To Darwin’s credit, he brought Wallace’s essay and his own notes to a scientific society in London to share and make public the two conclusions.

Darwin’s book came out first, while Wallace’s book on natural selection never fully actualized. Wallace’s biography tells, “were it not for Darwin, the nineteenth century probably would be known as Wallace’s century.”

It didn’t help that Wallace’s interests took a turn towards the spiritual. He became a spiritualist. Spiritualism and séances held a unique thrall over members of Victorian high society who had otherwise departed from conventional religion.

Wallace, along numerous other famous British personalities, marveled at séances and, against all scientific credibility and in spite of hucksters and frauds– affirmed that some aspects of spirit possession was true. He took on other topics no one dared write about, such as is there life on Mars?

Maybe it’s no surprise, then, that Wallace believed angels were real. According to biologist and writer Rupert Sheldrake, Wallace thought that the evolutionary process itself was guided, supported, and “led by creative intelligences, which he identified with angels.”

Natural selection helps us understand how species evolved, but whereas Darwin and the scientific establishment left their theories at what was demonstrable, Wallace was dissatisfied with purely a materialist view of life. He was not willing to let go of the strangeness of spirituality and science. Wallace’s last book was titled The World of Life: A Manifestation of Creative Power, Directive Mind, and Ultimate Purpose.

You can imagine how Wallace’s scientific colleagues responded to his extracurricular conclusions. He became sidelined and mocked. Where he once had an amicable rivalry with Darwin, there now was cold, incredulous distance.

What kind of world do we live in?

In the 17th century, most scientists affirmed the universe functioned like a machine according to perfect rules of order. As scientists began categorizing more information about the world, and as scholarship on the Bible started to ferret out what really happened and what could never have happened, some of the mystery and magic went underground.

Newton himself studied the occult and alchemy, but had to keep it a bit of a secret.

Today, it’s as if the sciences themselves have evolved to be far stranger than our faith.

The faith of many in progressive Christianity still operates in a reasonable, respectable framework while the universe is what’s hard to believe.

Angels, along with a larger universe vision of Christ, can help us recover our wonder and the strangeness of faith.

What if the strangeness of faith is not separate from the strangeness of the universe?

Finally, I want to end with a tantalizing correspondance between mystical writers and potential scientific realities. In a book entitled The Physics of Angels, a dialogue between theologian-mystic Matthew Fox and scientist Rupert Sheldrake, the two merge what is nearly unthinkable in some circles (physics and angels). Thomas Aquinas, for example, Fox says, wrote that angels could move from place to place without any time elapses. Well, Sheldrake responds, this also is what a photon of light does—it moves without time elapses while it is traveling. Aquinas also thought that angels have no mass, no body. Sheldrake says that photons, too, are massless, only detected by their action.

In other words, their remarkable dialogue gestures a new frontier of possible meaning, that the physics of light may correspond with some visionary descriptions of angels.

My goal is not to convince anyone to believe or disbelieve in angels. Rather, is to invite you into a faith posture towards God, Christ, and the universe that embraces the unknown, mysterious, and strange. This posture dares to affirm and experience that the unknown, mysterious, strange universe reciprocally embraces us back.

Photo by Lukas Meier on Unsplash