Author’s note: Yes, I’ve read the book.

Canaan Mountain is almost unbearably symbolic.

It’s a great slab of sandstone strewn with the sturdy plants of the desert. It rises alone in the desert, hovering above Colorado City, Arizona (home of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Warren Jeffs’s people, modern polygamists) like a red-dark thundercloud, or perhaps, a thick pillar of fire.

Old Testament analogies are irresistible. Canaan Mountain breaks the endless skyline of a desert on the outskirts of civilization. It might be Sinai, giving refuge to the exiled people of God, a place of commandment, reorientation, covenant. Or, given its name, it might be Nebo, marking the brink of the Promised Land, the place where God’s chosen pause one final time before heaving themselves into motion and reclaiming the land of their birthright.

This, however, is the use Jon Krakauer makes of the mountaintop: a hardbitten former member of the FLDS church takes Krakauer up the slopes and sagely observes while sitting on an overlook that the mountain “seemed like the only place where the religion couldn’t control us.” (327) Indeed. This is the true subject of Krakauer’s book: its narrative wanders from the central story of the mentally disturbed Lafferty brothers, for whom the twilight religion of Mormon fundamentalism became fuel for violent insanity, into the nooks and crannies of Mormon history more generally and, at the broadest level, into dime-store psychology of religion in total. Religion, for Krakauer, begins with fantasy, progresses into control, and ends for some inevitably in violence.

The mountains of scripture are great rock embodiments of the religion of scripture, which is fundamentally about liberation: from sin, from slavery, from our own failures. That this man turns the symbol upside down shows us that Jon Krakauer reads religion from a different perspective. The mountain of Under the Banner of Heaven illustrates what Krakauer understands religion to be, which is, fundamentally, captivity.

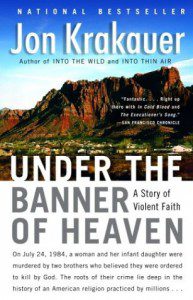

Canaan on the cover looms over the tiny town below it; it may be a site of escape for LDS dissidents, but to the person who picks up the book in the airport, it’s the grim and disapproving face of God. The banner of heaven is hard, gritty, unforgiving rock. In scripture, civilization means Babylon and Egypt. God’s mountain was a welcome escape; its wildness meant freedom and the presence of the living God. For Krakauer – whose work always dances on the edge of the seductive and destructive extremes of the American wilderness – the desert is dangerous, its wildness frighteningly far from the safe rationality of American cities, and the mountain is its apotheosis.

The stark danger of Mount Canaan is reflected in the text beneath the cover photo. It presents itself as dispassionate magazine copy. The font is serious and blocky, and the horror that the words have to tell are all the more distressing for being marched out in this square, flat layout. But graphic art can’t hide the book’s true progenitors, and the text itself betrays them.

The lines on the cover tell us of the Lafferty brothers, and the murders they committed. Then it slyly, ominously, in Robert Stack’s voice, tells us that “The roots of this crime lie deep in the history of an American religion practiced by millions. . . .” The ellipses are not mine. They whisper of conspiracy and corruption curdling under the surface of this small town, and, adding their worry to the looming image of Mount Canaan, we cannot conclude but that religion is dangerous.

Under the Banner of Heaven’s literary parents are Arthur Conan Doyle and Zane Grey, Robert Louis Stevenson and Jack London – all who wrote nineteenth century penny dreadfuls premised on the notion that Brigham Young’s Zion was a totalitarian dictatorship, complete with secret police and young Mormon maidens pining for rescue from the grimly-bearded elders of the church. How could a religion in which people told you what God wanted for you be anything but?

The idea stands particularly offensive to a man like Krakauer, who resembles something like a sober Teddy Roosevelt. Into Thin Air and Into the Wild, his previous books, stand in a long line of creation myths: Walt Whitman, Thoreau, Frederick Jackson Turner, writers for whom the American character in born in the bloody labor of the heroic individual subduing the wilderness – and in the process, becoming a bit wild himself. Krakauer’s work tends to bend a bit toward the tragic (he can never decide whether he admires Chris McCandless’s moxie or despises his naivete), but the myth of the fiercely independent American, reliant on nothing but his own wit and skill, rests deep in him nonetheless. The special horror of Canaan Mountain, then, the wilderness itself bent into the service of anything so demanding on the individual as religion, is for him particularly repellent.

Krakauer’s myth is strong. His book is still, ten years after its publication, regularly among Amazon’s bestsellers on Mormonism. But this may be so because the myth is not his alone; Krakauer echoes the fears that Americans have long held, that their freedom might be subdued by a featureless, stony institution, their independence bent into enslavement. The story is compelling, and Krakauer is writer enough to make it gripping. But this is not to say that it is less myth than he believes his subject to be.