[Yesterday, I had the privilege of virtually attending the blogging event held in honor of the Joseph Smith Papers most recent contribution: Histories, Volume 2.]

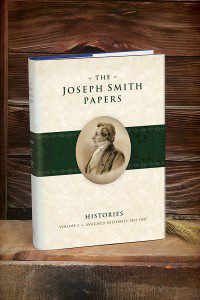

On the day the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was organized in 1830, Joseph Smith claimed a revelation that “there shall be a record kept among you.” The Joseph Smith Papers Project, which has been going strong for over a decade and has now published its sixth of a projected twenty to twenty-five volumes, is perhaps the most ambitious and significant result of that charge. Endorsed by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, the project has taken Mormon documentary editing standards to a new level and established a pattern nearly impossible to duplicate. The most recent volume, the second in the “Histories” series, reproduces early attempts to narrate the Church’s history prior to (and immediately after) Joseph Smith’s death. Unlike the first volume in the series, though, these texts were not directly overseen, dictated, or even supervised by Smith himself; rather, they were commissioned by him and composed by others who claimed their own first-hand experience.

On the day the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was organized in 1830, Joseph Smith claimed a revelation that “there shall be a record kept among you.” The Joseph Smith Papers Project, which has been going strong for over a decade and has now published its sixth of a projected twenty to twenty-five volumes, is perhaps the most ambitious and significant result of that charge. Endorsed by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, the project has taken Mormon documentary editing standards to a new level and established a pattern nearly impossible to duplicate. The most recent volume, the second in the “Histories” series, reproduces early attempts to narrate the Church’s history prior to (and immediately after) Joseph Smith’s death. Unlike the first volume in the series, though, these texts were not directly overseen, dictated, or even supervised by Smith himself; rather, they were commissioned by him and composed by others who claimed their own first-hand experience.

That is an important step in the process of Mormon historical writing and deserves reflection. Even if those assigned were, at least at first, faithful and committed to the cause, their texts’ distance from Joseph Smith introduced new possibilities for interpretation: the narration was now no longer held in control of one person. Such a dynamic necessitates the introduction of nuance and diversity, because everyone experiences and interprets things differently, even if drawn from similar events. The individual and independent nature of these documents may seem alien in a day when everything must go through a rigorous correlation process overseen by many men, they were part and parcel of early Mormonism, in which personal experience drastically differed depending on background and personality. Reading through the accounts included in Histories, Volume 2, it becomes quickly evident that what is presented is not a single, unified account of what happened to the Church during Joseph Smith’s days, but how various individuals experienced and interpreted those events. For an average Latter-day Saint, such a systematic study would be enormously important because it provides not only details of early Mormon history, but a methodological lesson in how histories are constructed.

Perhaps more important than the types of authorships are the actual authors. The volume includes a multivocal account from various perspectives: from fully-committed members publishing in the Church’s newspaper to excommunicated dissidents who never published their controversial accounts. It should bee seen as significant that among the authors are John Whitmer and John Corrill, two individuals who left the Church during the 1830s and whose disillusionment colored certain aspects of their histories. Their accounts, then, present a much more anxiety-ridden and complicated look at Mormonism’s origins and detail the problems faced by those who attempted to follow Joseph Smith’s often-difficult commands.

An important and sometimes overlooked aspect of the Project is their seamless integration of digital resources. While the books (deservedly) receive much attention, it is significant to note how much work is put into their online presence. Besides providing high-resolution scans for the specific Joseph Smith documents reproduced in the volumes, the Project’s website goes far beyond by providing documents not included in print. This is especially the case with the Histories Series, as there are numerous historical accounts that just fell short of the “Joseph Smith Document” criteria (mostly due to the fact that they weren’t individually commissioned by the Prophet) but are still worthy of mention. Another notable example is the History of Joseph Smith series begun in 1838 and continued long after Smith’s death. But even though these documents won’t be found in the printed volumes, they can all be found online, along with an amazing cache of other documents that are continuously uploaded. Other web features include comprehensive indexes, glossary terms, geographical descriptions, and biographical aides.

These are all significant and welcome features, especially in a world where even religious experience seems to be migrating to the digital realm. The fact that the Church has had difficulty maintaining young adults is not a secret, and the role of the internet in the many de-conversions is becoming increasingly apparent. When the Church doesn’t provide responsible and open accounts of its history, today’s generations will look somewhere else–and, barring a few exceptions, most websites that claim “objective” and “unbiased” histories of Mormonism are anything but. Though admittedly late to the game–though one would hope not too late–these types of digital elements are necessary to reach a generation that is more comfortably trusting the internet than correlated manuals.

Complexity. Plurality. Immediacy. Digital conveniency. These are key issues when dealing with the 19th century origins of a 21st century church.

______________________________

See also the short videos they prepared on the volume, found here.