“We can keep being friends, just so long as you know you’re a bad one!”

“We can keep being friends, just so long as you know you’re a bad one!”

What a line. Hannah Horvath, everyone’s favorite narcissist, coked out of her mind and newly freed of her inhibitions, captured the entire ethos of the show Girls, in 15 words.

The scene came back to me when I saw yesterday’s new trailer for the next season of the show. It looks fabulous. Hannah’s cut her hair! Jessa’s reappeared from Peru/Bali/the South Bronx! The inevitable manslaughter-suicide of Ray and Shoshanna has yet to take place! Adam’s hair is weirder than ever, and Marnie’s constant subversion of the world around her continues to fly under the radar! Everyone is intense and profane and no one is ready to claim the mantle of adulthood yet. And they’re all friends, even if they hate each other for being bad ones.

Love and hate go hand in hand on this show. It’s a heady mix of recklessness, untrammeled affection, fatal boredom, blind privilege, untreated mental illness, and most of all, judgment. Everyone else is doing it wrong, not that anyone knows what right is. While the resulting explosions make for some truly great scenes, it’s the judgment part that’s key.

Hannah has been very easy to dislike, if not abhor. She’s been criticized (inside and outside the show) for her entitlement, her self-obsession, her inability to recognize the needs of the people in her orbit, and at times her outright cruelty. She—rather, Lena Dunham, the woman who writes and plays her character—has even been accused of racism.

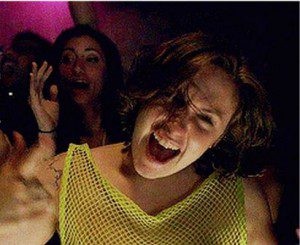

However, “Bad Friend,” the episode quoted above, and the one right after it, “It’s a Shame About Ray,” laid Hannah bare, giving us a reason why, even at her most ridiculous points—being trailed by a junkie neighbor through a Duane Reade, yelling at a bathrobed Marnie in a twerpy artist’s house while wearing a neon mesh shirt that thoroughly undermines her ability to throw shade— she’s worth watching. For the first time, we got to see why these people love each other in spite of all their selfishness, and why they come back. Later on, Jessa sits naked in a tub with Hannah and cries, spiritually and physically raw, in the way you do when your life has fallen around your ears. Then she snorts a booger into the tub water. And Hannah lets her. If there’s a better example of the show’s interest in ‘what is’ rather than ‘what should be,’ I can’t think of it.

In a piece for Think Christian, Daniel A. Siedell argues that the art world is still chewing over that transition from the idealized world to the natural one: “the artistic establishment pillaged nature in order to perfect it, using it as a backdrop for classical and Biblical stories that shaped virtue or delighted the soul.” This process created some sublime art, to be sure. But it could also be as reductive, in its way, as the all-too-common idea that scripture exists merely to tell us how to behave. (Or that television criticism is about policing the behavior of people who don’t exist anyway.)

By contrast, the modern tide, says Siedell, “returned painting to the realm of the creation. These paintings are worldly, creaturely. The critics noticed this. One hostile critic claimed that Cézanne could even paint bad breath.”

The new breed of painters, in their dedication to capturing something about the world that was decidedly less platonic, less “spiritual,” were creating an ethic of their own, dedicated to bestowing dignity on the imperfect world. He quotes Cézanne: “You don’t paint souls, you paint bodies; and when the bodies are well-painted, dammit, the soul – if they have one – the soul shines through all over the place.”

Which is why the line “Just so long as you know you’re a bad one” landed, right in the midst of the critical firestorm over Girls, in a way that gestured as much towards the show’s place in the television landscape as it did Marnie’s mistakes. Hannah’s self-consciousness has always mirrored the show’s self-consciousness, and it was as if Lena Dunham reached out to grab us and say that we could, finally, stop worrying about whether Hannah will ever do anything “right.” To me, at least, it presented an argument for the show that didn’t require us to think of these characters as role models or cautionary tales. We’re friends either way.