Occasionally, I get asked whether or not I ever actually left my old fundamentalist church. My story on No Longer Quivering followed my journey up to the first year of college. I’ve wrestled with how to explain what happened in a proper narrative form, because the circumstances that led to my cutting ties completely with the church ranged from financial to emotional to practical to ideological. There’s not a clear, linear story from here on out, just a constellation. But I’ve decided that it’s high time to tie up the loose ends and explain how, exactly, I cut and run.

When I first went to college, my mother still picked me up for our weekly drive to church. In fact, the first semester I was at college, I had to petition my professors for special permission to go on a trip to Sabino Canyon, AZ, a “holy place” (I use the term loosely) for believers of the Message of the Hour. It was the site at which William Branham claimed to receive important revelations from God, and my whole church was renting a plane and going to see it. I may yet write about this experience in the future. Suffice it to say that, for the first semester of college, I was living peacefully in the dorm six days a week and then being wrenched out for an hour-long drive to hear about the end of the world from my pastor, just like I had been hearing for years.

Something happened, though. Moving out of my parents’ house made a huge difference in how I perceived church relative to the rest of my life. Since we attended church weekly and my mother listened to Branham’s sermons all week, I had been up to this point immersed in the Message. It was always on the brain, either from hearing sermons my mother played or looking at the Hoffman’s Head of Christ on our wall or just seeing the Message books scattered about and feeling guilty if I hadn’t read one recently.

Until college, I only experienced normal, mundane life occasionally, like when snowstorms canceled church and I was out of touch with church people for more than a few days at a time. I fell in love with everyday life every time, because it was so rare to stop thinking about the end of the world, my own guilty conscience, and the perils of the Rapture. Moving away to college removed that constant anxiety, allowed me to immerse myself in mundane life completely. Coming out of that state of relaxation to go to church was suddenly even more jarring than it was on those rare occasions when I let myself forget before. I was effectively living in two different worlds, and the college world was full of nice people who weren’t worried about whether nuclear bombs would drop the next morning.

I started to realize that going to church made me sick, so I dealt with the problem with the best passive aggressive tools in my collection. When final exams started to bear down and my workload got intense, I told my mother I couldn’t spare the time to go to church. Gradually, the pattern we had established (where going to church was the default and I had to ask to be left behind) reversed (so my mother would call to ask if I was coming to church) and I stopped altogether. I did this so slowly that I didn’t think of myself as “leaving” for another six months, at least. I was too afraid to even imagine “leaving” as an option yet.

While I was away, the song leader began mailing me CDs of the sermons I was missing. I stacked them in the bottom drawer of my desk in the dorm and felt enormously guilty whenever I looked at them. But I realized that I had no desire to hear them. They were threatening, somehow. Then, over spring break, I sneaked them all into my mom’s house and left them there. I told myself I was getting some space to think about what I really believed, because I wasn’t feeling the convictions so strongly anymore and I was absolutely possessed with the idea of living an authentic life, being honest with myself. I told myself I was just thinking it over because the alternative was too scary: I had heard the horror stories about youths leaving the church and winding up addicted to drugs, or with cancer, or in some other dire spot that was the spiritual consequence of blaspheming the prophet of God.

During this time, I made friends with a Catholic and an atheist. The Catholic was determined to get me to talk about my faith, which was the last thing in the world I wanted to do. All I wanted to do was hide. I was careful to say that I respected the beliefs of my church despite how unsure I was about my own relationship to it, because to say anything critical would mean to blaspheme the Holy Spirit by speaking ill of God’s modern work. Every time my Catholic friend insisted on questioning me, I emotionally curled up like an armadillo and tried to avoid dealing with the implications of what we were talking about. My Catholic friend did me a world of good, as much grief as I gave him for trying. I needed to be challenged, as much as I didn’t want to be. His simple curiosity was not meant to tear down the pillars of my faith at all, but that’s what happens when you shine a flashlight through swiss cheese. It became impossible to ignore the holes.

In the meantime, I began to realize that the kindest people in my life were at college, not church. I experienced love and acceptance at college, not church. I was respected at college, not church. And so on. I wondered why the spirit of God seemed to be everywhere except his house.

After a full academic year spent nursing these questions against my will, I took the hardest step. I decided not to go back. That week, I went to the mall and bought a pair of jeans – they were the wrong color and about four inches too long, but they were my jeans. The first pair of pants I had worn since I was six years old. Pants were liberation. I saw the pants as a radical statement of honesty: Hey, God, I don’t believe wearing skirts is spiritually necessary. If I’m wrong, it’s up to you to convince me, not anybody else.

A financial crisis set in that spring that threatened to keep me from continuing my degree. Then both of my parents became grievously ill. This compounded stress caused me to turn to my one “best” friend, the person I was sure was in my corner: Sven. The boy I’d sworn I loved despite not being allowed to love, according to the emotional purity doctrine that says you can’t form attachments to the opposite sex unless you’re getting married to that person.

He let me down.

That strange, deep, driving force that had been pushing me to live authentically bubbled up and said, with the clarity of a real human voice, He does not care about you.

Driving that revelation home was the statement one of my roommate’s friends made to me earlier in the academic year, as I fumbled to explain how I could be emotionally committed to someone without actually dating them. We’re not allowed to date, I had said, knowing I made no sense, but we’re sort of understood as together. “No, you’re not,” said the friend candidly. “If he was your boyfriend, he would call himself your boyfriend. He would call you his girlfriend. You’re single.”

This reality check, just like the curious poking of my Catholic friend, made me very angry. It tore down the fantasy I had built to protect myself from a harsh truth: that I didn’t really have the support I thought I had in church. People cared about me, but not that much. I was dispensible. I had wanted to believe in a love that didn’t exist, because the alternative was too scary: before college, I’d had nowhere to turn.

A card drifted in on the mail from a girl I had never gotten along with, telling me she sent her love and was concerned about my spiritual health because she hadn’t seen me at church in a few months. I didn’t answer. It was becoming clear that my value to the people I had grown up with was in my conformity, in my continued presence as part of the flock. Only one person reached out with a genuine, “I miss you,” to which I responded as best I could. The rest just watched me go.

The farther I got away from the regular dosage of fear I received over the pulpit every Sunday, the more contrived and illogical my old faith seemed to be. Not the presence of God – I was sure I felt that more at college and alone in the woods than I ever had at church or listening to sermons – but the doctrinal contraption that had been built to contain it.

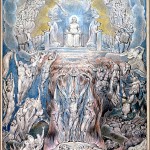

I realized that I only believed the Message of the Hour because I was scared out of my wits. I was told the world was ending, that it was nigh impossible to make the Rapture, and that the only other way to avoid Hell was to give my life as a martyr in the Great Tribulation. I had consented to everything else – skirts-only, courtship, purity culture, the modesty doctrine – as a bargain to save my life. Once I realized that my life wasn’t actually in danger, the whole structure fell apart.

And that’s how I left, without realizing I was leaving until I was gone.