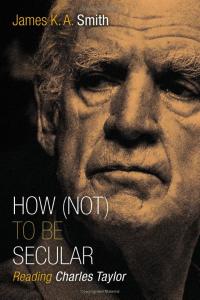

What’s Your Name? How (Not) to Be Secular

The story of Joseph is a story of how members of the family of God become secularists. Charles

The story of Joseph is a story of how members of the family of God become secularists. Charles

Amazon.com

Taylor, in A Secular Age, defines secularism as a culture where belief in God is no longer the default setting. Let Egypt stand for our modern secular culture, and Joseph stand for the people who have left church to become secular. Can we get back to where we belong? This is our question. The theme: There is no undoing of the secular, but can we learn how not to live secular lives.

With each passing day, faith seems to recede in America. Either it goes down the rabbit hole of an austere fundamentalism screaming at the top of its lungs about “literalism,” or it embarks on a spiritualization that denies the bodily, fleshly nature of Christian faith, or it retreats into the wasteland of secular, “exclusive humanism.” Genesis 12 – 50 chronicles how faith disappears across generations.

The disappearance of faith

As we work our way through Genesis, from Abraham to Joseph, we see a fading faith. Abraham was the father of our faith, by the time of Jacob, he had become a scoundrel and a thief and then Joseph a member of the Egyptian court. Features of faith that were so obvious in Abraham disappear as Joseph embraces Egyptian secularism.

And it takes a considerable amount of time for this erosion to happen. Faith never dies easily. That means there are always opportunities for a “return”.

More than that, Joseph is the secular man. By the time Jospeh ends up in Egypt – he has become totally secular. I am convinced that this is the current trajectory of American faith – secularism. And much of it happens unconsciously.

Joseph assimilates into Egyptian culture, Egyptian thought, Egyptian politics, and with each compromise, each decision, each step, Joseph moves away from the faith of his ancestors. Joseph dresses like an Egyptian, talks like an Egyptian (those funny accents heh?), thinks like an Egyptian. He’s eating Egyptian food, drinking Egyptian wine, and hanging out in Egyptian night clubs.

He gets an Egyptian name – Zaphenath-Paneah; an Egyptian wife, Asenath. Asenath has two sons, but Joseph doesn’t give them Egyptian names. He names them Manasseh and Ephraim. A pair of Hebrew names offer the first glimmer of hope. Maybe secularization can be reversed in a family.

And if there is any remaining doubt about Joseph being Egyptian, Genesis closes with these words: “And Joseph died, being one hundred and ten years old; he was embalmed and placed in a coffin in Egypt.” An Egyptian funeral, presided over by an Egyptian priest, and buried in a coffin in Egypt.”

A later tradent of Genesis inserts another narrative suggesting that Joseph left instructions for “his bones” to be dug up and carried out of Egypt. This attempt to cover Joseph’s totally secular commitments seems a bit weak. Walter Brueggeman tags Joseph as a “fourth-generation sellout.” He notes that the Jewish mantra of faith became “The God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.” Why doesn’t anyone ever add “and Joseph”? Joseph, Brueggeman argues, has to be dropped because he became so Egyptian, in my term, so secular.

When Our Story Becomes Secular

When we die will we be placed in a coffin in Egypt (the land of the secular)? Will a Christian pastor preside over our funeral? Probably yes for the rest of this generation. The remnants of the church that still cling to even the most secular of us are “baptize, marry, and bury.” But what about the fifth, sixth, and seventh generations? Will the later members of our families receive an Egyptian funeral, presided over by a Egyptian priest, a secular guru, a positive thinking con artist? Is there any hope left for us?

What about our developing secularization? Philosopher James Smith says, “We’re all secular now.” The secular touches and tarnishes everything it touches. We are all living in a globalized Gotham now. The Joker is everywhere, and the joke may be on us.

There’s a disturbing verse at the end of Hebrews 11 – the faith chapter of the Bible. After praising generations of the faithful, the preacher of Hebrews leaves us with this sobering thought: “Apart from us, all the generations of the faithful, will not be made perfect.”

So, if you are lying around the apartment on a Sunday morning you should know that the entirety of your family, all the way back to the first one, is depending on you to keep the faith. No matter how far you may drift from the church, you have been elected to represent your family – all of the long generations. I, of course, know that this will not suddenly drive young people back to the church; I just want them to feel guilty for not doing so. Such guilt will be a sign of hope.

Joseph, the secular man, operates in a political sphere that has no morals, no ethics. Brueggemann suggests, “Joseph understood so little and valued so thinly the God of the promise that he served greedy interests that victimized his own people.”

A Name. A Family. A Reconciliation

Joseph Forgives His Brothers —

Watchtower ONLINE LIBRARY jw.org

But thank God that is not the end of Joseph’s story. There’s more yet to come. There’s hope yet to be unleashed. And it happens in Genesis 45.

All of Joseph’s brothers are there. They don’t recognize Joseph, but he knows them. He has been working out his “residual resentments,” but then something happens. Suddenly, Joseph loses all pretense of being a powerful, revenge-obsessed politician. “Joseph could no longer control himself.” He cried out, “Clear the house,” or as the president in all our movies puts it, “Give us the room.”

And Joseph wept so loudly that the Egyptians heard it out in the hallways of the palace. One of Joseph’s interns must have asked, “What’s up with his highness?”

And then the entire story becomes a prelude to gospel. “I am your brother, Joseph.” We have a name: Joseph. Manasseh and Ephraim. We belong to God. Here’s the hope. A name. A family. A purpose rooted in God’s long vision for the future. Secularism can be thwarted.

Joseph remembers that he is not an Egyptian despite his Egyptian robes, rings, and riches. Joseph remembers his identity. He knows that he belongs to God, that God has a bigger dream for Joseph and his people than Joseph ever had for himself. Joseph sees for the first time that it’s not about him, it’s about what he can do for his people.

There is a way back from a secular wilderness for all of us.