{Perhaps my favorite thing about this season is reminding readers (and myself) how subversive are the Christmas stories. Before reading this column, I suggest you read Part One HERE.}

The Christmas stories in Matthew and Luke[1] served as preludes, or overtures, to those gospels. They encapsulated in miniature the “good news” of the larger piece and are the lens through which to read it. For readers living under the weight of imperial violence, including systematic economic and religious oppression, spying, collective punishments, rule by fear, and outright aggression in the colonies—violence that during the conflict in mid first-century Palestine burst into all-out war with accompanying rape and torture and tens of thousands crucified, the Christmas stories would have been emboldening, and in certain ways satirical. If we’re going to understand them at all, we must remember that this context inspired the gospels and their Christmastide overtures, and what it meant for a poor man like Jesus to show us and invite us to participate in the incarnation of the Divine in this world—what it meant for him to be lauded with appellations reserved for the Caesar.

In Luke, an angel appears to shepherds (a particularly low status) to herald the birth of this child Jesus who they call “Savior” and “Lord,” absconding Caesar’s titles—titles imperial subjects were imprisoned and killed for refusing to ascribe to the Emperor. Later, Luke portrays Jesus being recognized in the temple by the prophets Simeon and Anna as the one who would be “the redemption of Jerusalem,” the city those reading the gospel in the decades after its creation knew to be recently decimated by Rome. In Matthew, after a long genealogy linking Jesus to the patriarchs, an angel appears to Joseph explaining to him that Mary, his betrothed, will miraculously give birth to a child who will be the salvation of Israel. Magi from the east come to King Herod, Rome’s client king in Palestine who reckoned himself “King of the Jews,” and the Magi ask, where is the child who has been born “King of the Jews”? The story is a direct challenge to all the colonizing rulers Herod’s character represents. Even the very stars align to direct the Magi to baby Jesus, who they shower with gifts fit for a king: gold, frankincense, and myrrh. In parallel with Israel’s story, the holy family must flee to Egypt to escape Herod’s narcissistic baby-killing rampage in Bethlehem.

I find these Christmas stories both challenging and enlivening. If the Christian tradition just sanctioned the status quo, the “domination system,” it would have nothing interesting to offer. It would be another domination narrative by those seeking to advance their tribe and their egos. But the Christmas stories are microcosms of the gospels of Matthew and Luke, or overtures, and as such reveal a rich counter narrative to the domination system’s way of violence, oppression, and greed. There is so much to love here!

So too, there is so much that challenges us. I am an American who—like many Americans—benefits from being a citizen of history’s most far-reaching empire (this, added to the benefits of my being part of the dominant group in America). Almost all Americans benefit from our country’s geopolitical domination, whether in the form of relatively low prices at the market and gas pump, freedom of movement around the world, or in other ways. It can be so easy to forget or to “choose not to remember” how we benefit from the systematic domination of people in our own time and historically. And it can make it hard for us to understand the power of the Christmas stories, the confrontation leveled by Jesus.

This Christmas, may we have our ears tuned to hear its subversive message, and may we invite real understanding and all of the reparative efforts it demands of us. If “the first are to be last, and the last first,” it will be so because we actualize this vision in our own spheres of influence, living out the “way of peace” that Jesus taught us.

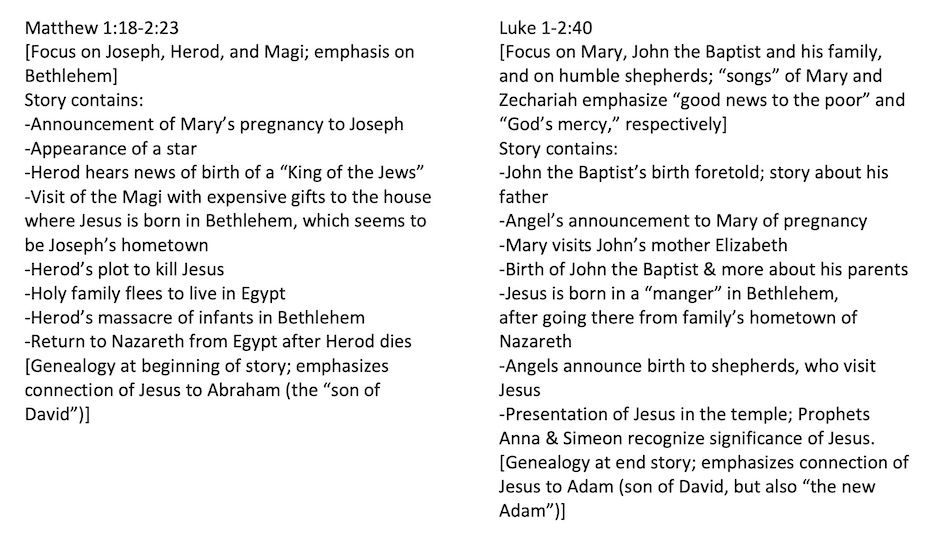

[1] The narratives in Matthew and Luke are quite different, as shown by this chart summarizing their key points:

Wren, winner of an Independent Publishers Award Bronze Medal