It is one of those weeks where everywhere I turn, folks are talking about the “epidemic of loneliness,” including an excellent recent interview of Robert Putnam, author of the book Bowling Alone (published in 2000), who said: “…what we’ve seen over the last 25 years since the book was published is a deepening and intensifying of that trend. We become more socially isolated, and we can see it in every facet of our lives.”

The breakdown of connections to traditional institutions always garners mention in these discussions, as exemplified in the recent New York Magazine article on loneliness quoted below. In conjunction with this, reporters are noticing a heightened, main-stream-ized interest in things like astrology and tarot, which give people a language for talking about ultimate concerns apart from religious traditions and the once long-established frameworks religions provided humans for these discussions.

I am very sympathetic to people’s reaching-after, as I believe strongly that we all need language, imagery, and stories by which to investigate our lives and experiences, and by which to talk/think about things far bigger than ourselves. People should find meaning where it resonates for them—as long as it is not down avenues of prejudice and hate. We must all grapple with existential questions, and with loneliness, in our ways (loneliness being “the unavoidable human condition,” as my friend Brother Martin, a nearly life-long monk, used to say).

But something I wonder about is this: how does the hyper-individualized marketplace of spiritualities address the needs of young people? This is a concern amplified by psychologist and Harvard lecturer named Richard Weissbourd, researcher of loneliness, who says:

“ ‘…it’s impossible to look at the aggregate data from the 1950s onward, including a new survey by Gallup on weekly attendance of religious services, which sank last year to 21 percent of the U.S. population, and not feel that something has been lost.

‘I’m not suggesting that we should become more religious, but I want to just suggest to you that religious communities are a place where adults engage kids, stand for moral values, engage kids in big moral questions, where there’s a fusion of a moral life and a spiritual life,’ Weissbourd said at a talk held in March at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

‘A sense that you have obligations to your ancestors and to your descendants, where there is a structure for dealing with grief and loss,’ he went on, repeating his opening caveat. ‘I feel urgently like we have to figure out how to reproduce those aspects of religion in secular life.’

Earlier this year, Weissbourd and Batanova conducted a follow-up to their 2021 loneliness survey, adding an open-ended prompt in which lonely respondents could try to account for the presence of the emotion in their lives. Many subjects cited a lack of ‘meaningful connection’ as the primary culprit.”

This week as children venture back to school, and as school districts country-wide grapple with questions around cell phones and possible phone-bans during school hours, I am wondering at the confluence of three things: technology, declines in community including communities of faith, and epidemic loneliness. It’s not coincidental that these trends run a parallel course.

As I look far down the road, I intuit a time when young people will become more deeply disillusioned with distracting technologies and more hungry for community, including for spiritual communities. I suspect the turnaround will likely not come in my lifetime, but the hunger pangs are so evident that the feeding becomes inevitable.

In the meantime, how can we be part of the turnaround to deeper connection? I know that in my life, a grand reordering seems to be taking place. It’s about less striving and more sharing. Less ambition, more phone dates. Less scrolling, more presence. More community, less concern about ideological purity (“ideological purity” being the notion that we must agree with everything a group purports to believe before being part of that group). I want these things not because I’m especially virtuous, but because I feel the hunger at the pit of our collective stomachs, the hunger at the pit of mystomach. A hunger for things that last.

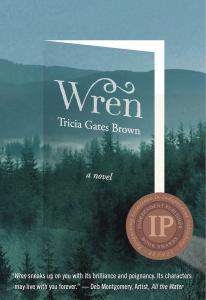

Wren, winner of a 2022 Independent Publishers Award Bronze Medal

Winner of the 2022 Independent Publisher Awards Bronze Medal for Regional Fiction; Finalist for the 2022 National Indie Excellence Awards. (2021) Paperback publication of Wren , a novel. “Insightful novel tackles questions of parenthood, marriage, and friendship with finesse and empathy … with striking descriptions of Oregon topography.” —Kirkus Reviews (2018) Audiobook publication of Wren.