First, a few years back, Yuval Noah Harari’s book Sapiens (2014) enthralled me. Now he’s got a new book out. While I’ve not yet read Unstoppable Us, How Humans Took Over the World, I enjoyed hearing him talk about it on a favorite podcast: ‘The Gray Area with Sean Illing.’ Harari makes some similar assertions in these books, namely that humans have transcended other species because—of all things—we were able to pass on great stories. Sacred stories. Shared stories. Basically, we prevail because we spin a good yarn; and a good yarn builds cohesion, allowing us the level of cooperation needed to accomplish great feats.

Prior to the ability to build group cohesion through shared concepts and values—through shared stories, groups tended to reach a breaking point at around 150—apparently the number able to directly know one another, forming face-to-face mutual trust. But stories or shared myths make possible a whole new level of connection, giving rise to understandings and agreements about critical abstract ideas—ideas like justice, transcendence, money, and family. It is these agreements that allow for cooperation. (And here I mean by the word “myths” sacred narratives, not fabrications). Our shared agreements and understandings make possible the mutual trust that allows collectives to develop into towns, then countries, and eventually into empires. Along the way, collectives of humans cooperate in the invention of both rapidly evolving technologies and more even complex sacred stories or mythologies.

This past week, in listening to Harari talk about his new book, I was struck by his concern that we’re losing our common stories, and by turns, our ability to cooperate to solve existence-threatening problems like climate change, nuclear weapons, and inequality. Here’s a key part of the conversation:

Illing: “I think in a lot of ways [humans are] still using the same language, but the words are coming to mean, very, very different things. And that process is accelerating and, and at some point, those founding myths or that paradigm that we’re all sort of operating in will come apart. What do you think happens to a community or a country or society once it stops believing in shared myths or its founding myth?

Harari: “…you cannot have a democracy in a place where people hate each other and see each other as their enemies and can’t agree on any common story. You can have political rivalries, that’s absolutely fine. Democracy is all about that. …But if you start seeing the other side not as your political rivals but as your enemies … out to destroy us… then democracy is simply impossible. You can’t force democracy on such a situation, even if you have elections. Elections are just a ritual in this sense.”

We need common stories because we need to cooperate. For most of our history, many Americans have shared common stories about our democracy, and even in some vague way about religion. Shared common religious stories matter. Even Americans from the faith traditions of Judaism or Islam shared some common scriptures/stories with the more demographically dominant Christians and were seen by many Christians as common adherents of the “Abrahamic faiths.” But in recent years, some Christians have adopted an acutely adversarial stance to those not like them religiously or otherwise—even toward Christians who are not like them (I find this article illuminating in this regard). Enter the scourge of Christian nationalism.

What do we do when our common stories break down on a massive scale, as seems to be the case for humans the world over and certainly here in the States? Harari—like many thoughtful people I hear these days—is concerned that the outcome won’t be good.

We need our shared stories.

I would include our religious stories. Religious stories matter (which is why my column is called “About Religion, Doubt, and Why They Matter”). But an indictment Harari makes against “many religions” is that they “don’t acknowledge that they were invented by human beings and therefore they don’t have a self-correction mechanism.” Self-correcting mechanisms, or adaptations, allow sacred-story traditions to continue to build meaning and cooperation among adherents to those traditions even as understandings evolve. Yet while I hear what Harari is saying and I sympathize with his indictment to some degree, the fact is, my close Christian friends are in liberal traditions that do acknowledge our sacred texts were written by human beings. Therefore, we hold that understandings of those texts can be adaptable; self-correction plays a vital role in our understandings of our traditions.

I resonate with Harari’s concern that loss of our collective stories is of great concern. And if we are to hold onto religious stories and the gift of cooperation these stories make possible—whether in working cooperatively for social justice, in helping people find meaning, in giving people language to talk/think about transcendence and concepts like self-giving love, forgiveness, trust, surrender, justice, death—we must make our religious stories adaptable. This means allowing for self-correction. This means acknowledging unapologetically the ways that humans wrote those traditions, including our sacred, inspired texts. God did not write the scriptures! Humans did. And our understandings of those scriptures can be fluid and adaptive.

Shared secular stories are important and critical—stories about democracy, for example. But these stories don’t always answer questions of purpose, integrity, love, and so forth. They do not necessarily address our inner life and our formation as moral agents. Stories from the religious/spiritual traditions have historically been pivotal in forming the ethical mind, the charitable heart, and the non-self-centered life.

As I walk through neighborhoods in the town where I live, I see stories on display through symbols. Pride flags; yard signs saying “Don’t give up” or “You Matter”; holiday decorations for Halloween or Christmas; signs for the Portland Trailblazers or for candidates running for election; MAGA signs. Shared stories are as important to us as ever. As we separate from stories that shaped people in the past, I wonder how the stories represented by these yard displays provide common ground to help us cooperate—cooperate on a grand scale to accomplish grand, much-needed projects, like sacrificing for the sake others and the planet.

Thank you for supporting my work by subscribing (free).

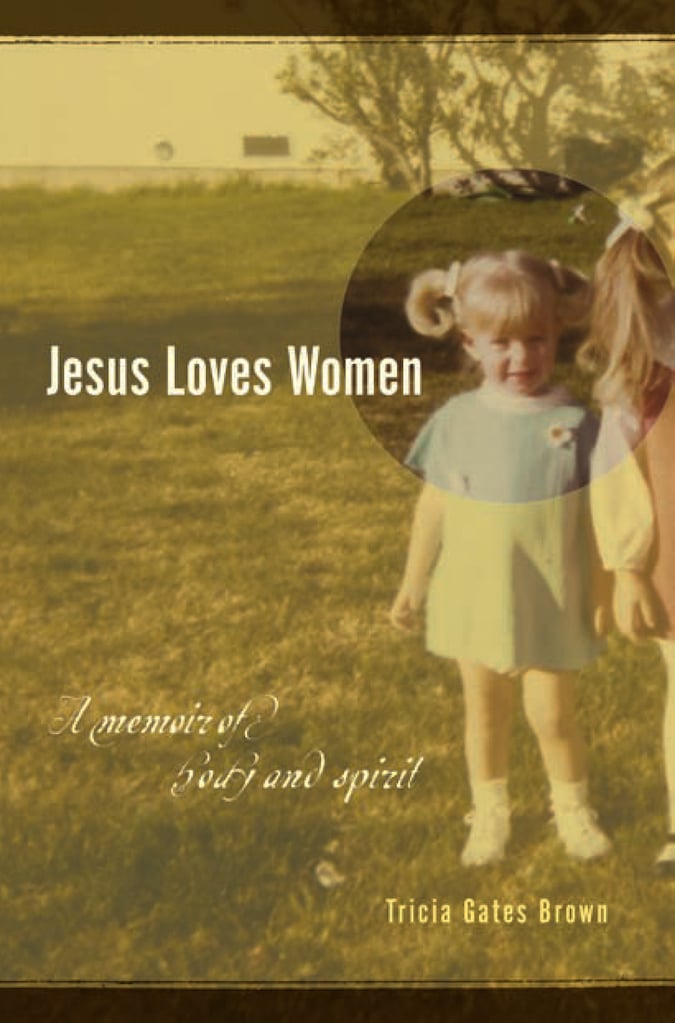

Available HERE.