What follows below is the text of my presentation at the session on blogging and online publication at the Society of Biblical Literature 2010 annual meeting in Atlanta.

The Blogging Revolution: New Technologies and their Impact on How we do Scholarship

James F. McGrath

When I begin with the question “What is a blog?” I am not asking it to insult the intelligence of those present here today, since I assume that anyone who has chosen to come to a session dedicated to blogging has come knowing something of blogs. But neither is my question a purely rhetorical one. I ask “What is a blog?” because, in the mind of many, the term

blog has connotations related not merely to

form but also

content. And I suspect that it may be for this reason that questions about the relevance of blogs to scholarship can result in raised eyebrows. There certainly are blogs which are completely dedicated to scholarly topics, but there are also a very large number of blogs that are personal, or which allow the personal and the professional, the humorous and the serious, not merely to co-exist side by side but intersect and overlap. And anyone who thinks that blogs are

by definition diaries unwisely posted in public for the world to read, or begin as scholarly enterprises but unfortunately inevitably lapse into discussions of LOST, pictures of LOLcats and humorous YouTube mash-ups, will inevitably see blogs and scholarship as, if not antithetical, at the very least distinct, and consider it appropriate that they remain so. And for this reason there’s a need to articulate clearly what a blog is, even if it seems tedious and unnecessary to do so.

As for the fact that even scholarly blogs may at times feature material or at least comments that are not focused on academic matters, it would be useful to have a discussion of whether and to what extent the breakdown of separations between professional and personal is inevitable in our Web 2.0 world.

I wonder how many of us have had conversations with other scholars on Facebook or a blog, only to have an old friend from high school or a relative chime in. The potential for personal and professional to intersect is not limited to blogs, but seems to be part and parcel of any public interaction via electronic means in our time, since our technological networks often fail to distinguish between personal and professional contacts. And rightly so – the failure to make such distinctions is a symptom not of the technology but of the fact that the categories of “friends” and “colleagues” are not mutually exclusive, nor should they be.

Returning to the question of what a blog is, the fact that there are blogs which are wholly dedicated to scholarly content indicates that the personal and frivolous are

not part of the definition of blogs, any more than the personal and frivolous are part of the definition of

books simply by virtue of the fact that there are books that fit those descriptions. The blog is a

format for making content available. One definition I came across recently, in an article with the title

“Portrait of the scholar as blogger,” defines the blog as follows:

“Blogging = Reading + Writing + Linking + Commenting”

That seems to me to cover more than blogs, and might work as a broad summary of what “Web 2.0” denotes. Blogs are characterized by all of the above, but also that posts on a blog are ordered chronologically. But with that further detail added, it seems that we do have here the essence of the blog expressed succinctly.

My reason for sharing this has nothing to do with the sense scholars sometimes get that we are running in circles. If we ask what the role of the blog is, and what the role of the blog can potentially and usefully be, in relation to our scholarly activities, then it may become easier to talk about the potential and limitations of the blog for scholarly uses. [It is worth mentioning that most if not all scholars are also educators, and while it may be useful for the purpose of this presentation to focus on scholarship, a discussion of the ways in which blogging relates to teaching and pedagogy, and ways in which blogs may cause scholarship and teaching to intersect at least as much as they cause the personal and professional to intersect, would also be a valuable conversation to have.]

So where does or can blogging feature in this diagram? If we begin (not arbitrarily) at “Research and Data Collection,” blogs have directly contributed to early stages of research in both direct and indirect ways. Indirectly, blogs have become places for sharing (and thus in the longer term repositories for) links to relevant sites. Search engines can sometimes help with finding things we need, but for new resources, scholarly sites in other countries, and databases that are extremely useful for academics but not particularly popular outside of a narrow circle of scholarly interest, you are far more likely to learn of these resources by visiting (or better yet, subscribing to the feed of) the blog of a scholar in the field in question, than by Googling. In addition to blogs providing indirect connections to useful primary sources and databases, blogs also provide access to many things that can contribute directly to a research project: a professor commenting on the current “hot topics” in their field; mentioning in passing an interesting idea that ought to be explored further, but which they themselves are not going to be focusing their research on; or simply sharing their thoughts in a way that might spark an idea in a researcher who reads them.

Also connected to the category of “research” as well as “analysis and interpretation” is the interaction – the “networking and sharing” – that takes place between multiple researchers collaborating on a project. A recent study on the “

Adoption and use of Web 2.0 in Scholarly Communications”

found that those involved in collaborative research were more likely to adopt Web 2.0 technologies than those who were not involved in collaborative research. This is true even if the collaboration is local. This suggests that the need to communicate with collaborators in research may foster the adoption of new technology. Personally, what I found astonishing was that there are still significant numbers of academics who, in spite of the usefulness of these technologies for collaborative research purposes, still have not embraced them, even though they themselves are engaged in collaborative research.

Overlapping the domains of “research” and “analysis and interpretation” are the scholarly conversations that increasingly take place between blogs in the form of interactive and interlinked posts, as well as in the comment section on individual posts on scholars’ blogs. I can speak personally that this is particularly useful to academics working at primarily undergraduate institutions, where they may be the only person responsible for teaching Biblical studies, having neither colleagues nor graduate students in the same area with whom to discuss ideas and current research interests. And so blogs are mitigating some of the traditional distinctions that placed scholars in very different situations across divides such as “Research 1 vs. Liberal Arts institutions,” as well as distinctions between scholars in Europe, North America and “Down Under” as opposed to other parts of the world. And since individual scholars, as well as scholarly organizations such as the ones under whose auspices we are meeting here today, are committed to the cause of greater equity of access to scholarship and scholarly resources, blogs seem to be already contributing to the achievement of such aims.

This is the real payoff of academic blogging and Twitter networks: a professor at a smallish school, without teams of graduate students or colleagues engaged in similar work, can nonetheless exchange ideas and problems with researchers worldwide.

It is our next stop in the circle, “authoring and presenting,” that relates most directly to what we are doing today. Perhaps the traditional mode par excellence of scholarly work is to write papers and present them at conferences. Publication in peer-reviewed journals is arguably even more definitive, but that is in most instances the next stop on the circle (publication/dissemination), and not a mutually exclusive one. A great many articles in major journals made their first public appearance as conference papers. And it is in relation to this area that blogs have the potential to change the way we do things most radically.

The academic conference is a very costly (if admittedly generally also very beneficial) endeavor. For some, it is a personal expense, while in other cases, it is an institutional one. And it is, I think, guaranteed that even if individual scholars and scholarly organizations do not willingly begin to ask questions about the efficiency and necessity of such events, our administrators will do so. What is the purpose of expending large amounts of institutional monies to allow a person to travel to another part of the country or the world, to accomplish something that in our time can be accomplished without leaving home? Papers are already submitted electronically and vetted by committees who are located all over the map. If we think of the actual reading of papers, it is already a widespread practice to circulate papers before the conference so that they can be summarized, leaving more time for discussion. But even when it comes to actual reading of papers, it is a simple matter today to record and post a presentation of this sort in video form, and many of us have embedded talks on our blogs in the form of vodcasts or podcasts. And as for discussion, surely this occurs more effectively over a period of time in the comments section of a blog than it does in the brief amount of time left for questions at the end of a paper (assuming the presenter finishes punctually so as to leave ample time for discussion). And so a question that is bound to be asked sooner or later is why are we still holding conferences? What, if anything, makes the expenditure worthwhile? Might videoed presentations be preferable to the current practice, especially when we consider how the proliferation of sections at SBL has led to our missing increasing numbers of papers that are of interest to us? Would a blog-conference not have the potential to allow attendance by scholars in countries and at institutions where the cost of attending a traditional conference of the sort we are at today is economically unfeasible?

I ask these questions as someone who values the opportunity to meet with colleagues at events like this one. The point is not that we should eliminate the traditional conference, but that technology is eliminating some of the traditional rationale for such events as this. And so if we are to keep meeting together in person, we will soon need to justify our doing so, and thus we should be thinking proactively about why we need conferences, and what they can most usefully be used for. In the future, the most typical classic features – the presenting of papers and the book exhibit – may be things more frequently and more effectively taken care of electronically. And so we need to ask whether conferences can evolve and adapt to this changing environment, and if so how.

As for disseminating the results of research, presumably there is little we need to discuss. Many traditional print publications can already be found in online versions, some of which incorporate space for comment and discussion. But one of the big questions confronting scholarly publishing is that of

open access. Should scholarly publications be hidden behind a pay-wall? And if not, who will foot the bill for providing web space for these materials?

Tim Bulkeley wrote recently in The Bible and Interpretation (an online publication, for those who may not be familiar with it):

In the age of the blog, and more generally of free or almost free electronic publication technologies, such a closed “publication” is the antithesis of open, public scholarship. In the sciences, such secretive commercial publication makes handsome profits for the shareholders in the businesses that “publish” reputable journals. In biblical studies, by contrast, no one profits. Scholars lose out because their work languishes unread. The public lose out because the work they paid to produce is hidden behind another pay wall. The publishers grumble because the income from subscriptions barely covers their costs. Conventional journal publication in the 21st century in biblical studies is a lose – lose game. [6]

Closely related to this is the question of the archiving of scholarship. If scholarship is accessible as never before, it can also vanish as never before. We are familiar with blogs that have been deleted by their author or hacked maliciously. How do we safeguard the preservation of scholarship in a digital age? This raises questions about format and location, but also conversion, so that future generations of computers can be ensured to display articles written today in spite of changes in software and standards.

But returning to the subject of dissemination, it certainly seems to be the case that blogs can be useful for sharing and promoting scholarship, and in this regard bloggers may seem to have had an advantage in terms of drawing the attention of those scholars and graduate students used to interacting online to their publications. As blogging becomes increasingly the norm, one wonders how the “biblioblogosphere” may change and evolve. Or to paraphrase

The Incredibles

, if everyone is blogging, is that the same as if no one is blogging? Has blogging allowed a limited number of scholarly technophiles to gain attention that they would not have if every scholar had a blog? Or do we look to certain scholars’ blogs not only because they are there in limited numbers, nor because that scholar has a certain scholarly reputation, but for other reasons?

To the extent that we are interested in not merely disseminating scholarship to other scholars, but also bringing scholarship to a wider public, blogs are clearly useful. The typical blog often bears a lot of resemblance to the newspaper column: it is a place where someone who is felt (rightly or wrongly) to have a certain expertise in an area offers opinion and commentary. And to the extent that blogs now overlap with and are substituting for such columns, they are a natural place to which scholars interested in public knowledge will gravitate.

But how effective are blogs in this wider dissemination of scholarship? How well do scholarly blogs reach a wider audience? This can be very hard to assess, but to the extent that scholarly blogs increasingly find themselves quoted (even if negatively) in all sorts of places, our blogging is presumably a good thing. And to the extent that we are concerned with reaching a public that turns to the internet for answers and does not normally search beyond the top few hits, anything that we can do to get our scholarly answers high up in search engine rankings is presumably to the public’s benefit.

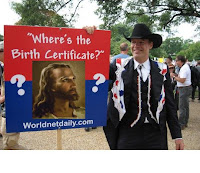

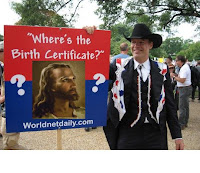

I can attest to my own blog, Exploring Our Matrix, getting attention from two very different and yet arguably very similar groups. On the one hand, I have had the “honor” of having some of my blogging that is critical of young-earth creationism mentioned by Ken Ham. On the other hand, I have had significant opportunity to interact with “Jesus mythicists” – those who claim that there is no historical figure Jesus of Nazareth to whom the New Testament gives us access, even if through a veil of legend and theological development. If the question is one of effectiveness, I do know of individuals who have changed their minds about these subjects. And if the question is whether the effort is worthwhile, I again feel I must answer in the affirmative. Science education is frequently under attack when local school boards are influenced by individuals whose perception of biology is affected by online young-earth creationist and intelligent design web sites. And the way it featured in Bill Maher’s movie “Religulous ” shows the influence that online mythicist sources can have and how they can end up getting significant attention. I presume that all of us who are involved in education are concerned about both the dissemination of reliable information, and the honing of critical thinking skills. And so, to the extent that online discussions of topics related to our field can at times be typified by approaches that are neither well-informed nor characterized by critical thinking, blogs provide scholars with an opportunity to illustrate both to an audience that will never enter our classrooms or read our articles and books.

” shows the influence that online mythicist sources can have and how they can end up getting significant attention. I presume that all of us who are involved in education are concerned about both the dissemination of reliable information, and the honing of critical thinking skills. And so, to the extent that online discussions of topics related to our field can at times be typified by approaches that are neither well-informed nor characterized by critical thinking, blogs provide scholars with an opportunity to illustrate both to an audience that will never enter our classrooms or read our articles and books.

“A couple of weeks ago, I shared the blog with my academic mentor – Michael Brown – who is the most brilliant man I have ever met. I have read more books with Mike than with any other person in my life (even more than with my 5-year-old and the effort required to read 1 Deleuze and Guattari must equal that of at least 100 Harry Potters). Mike looked at the blog and the numbers of readers, turned to me and said –

more people have read your blog than will ever read your book – even if it goes mainstream. He is absolutely correct.

So, why do we write?”

Presumably there are more reasons for writing than being read by as many people as possible. Those who write on politics might prefer to have the senate and congress reading their book and no one else, than everyone

but the congress and senate. Audience matters as much as if not more than sheer numbers. But to the extent that our aim is to write not only for academics but for the public, it is not clear that a widely-read blog is necessarily less valuable or even less influential than a contract with a trade publisher. If we write things other than peer reviewed publications that count towards tenure and promotion, blogs are part of the landscape now. And if our aim as scholars involves dissemination of reliable information to the public, then the route to accomplishing that is presumably to have

more scholars blogging, not fewer.

If we ask “

Is blogging the future?” we need to be careful to be more precise – the future of

what? If the question is whether blogs or other similar means of distributing information and interacting with others are here to stay, I believe they are, and I also am persuaded that they are making and will continue to make a positive impact on what we as scholars do. If blogging can become a distraction, so can many things, but blogging can represent a form of practicing the discipline of daily writing. And more than that, it can actually help us to meet deadlines, since we will not be able to have our excuses for missing deadlines taken seriously if we have been posting on our blogs at great length and with frequency during the period we were supposed to be finishing that book chapter.

As for whether blogging itself is likely to change the realm of scholarly publication, that is harder to say. My inclination at this stage is to agree with

Jaipreet Virdi of the University of Toronto, who recently wrote the following:

I doubt that blogs will supplant traditional scholarship (e.g. peer-reviewed journals), but as a blogger, I am open to their ability to stimulate conversations not available in traditional fora. Blogs create a new aspect of scholarly culture, an amiable digital ivory tower spearheaded by the open-access movement, a movement that presents fresh opportunities to educate or to influence public participation.

But let me conclude by emphasizing once more the point with which I began. Blogs are a

format and that particular medium can be the means to delivering a wide range of content. And so there is no need to be interested in any particular

use of blogs that has been mentioned here today, in order for it to be possible that blogs could be useful to you – whether for ends connected with research, pedagogy, networking, exploring side interests, or

any number of other things The truth is that academics have found many creative new uses for older technologies – the pen, the book, the web site – and one of the best things about scholarly blogging is the way in which the very act itself, in interaction with others, is leading to creative new uses of technology. But whatever new activities and forms of interaction we may develop and cultivate in the future, hopefully this brief presentation shows the relevance of blogging to the things we have

traditionally and

historically done as an academic community, and ways in which it has the potential to foster and even improve our effectiveness in those areas. And for both those of us who use blogs and those who have viewed them with skepticism, hopefully we can all find ways of working towards ensuring that as technologies continue to evolve and develop, we voice the needs and desires of the academy and play our part in driving technological change in directions that are academically useful.

When I begin with the question “What is a blog?” I am not asking it to insult the intelligence of those present here today, since I assume that anyone who has chosen to come to a session dedicated to blogging has come knowing something of blogs. But neither is my question a purely rhetorical one. I ask “What is a blog?” because, in the mind of many, the term blog has connotations related not merely to form but also content. And I suspect that it may be for this reason that questions about the relevance of blogs to scholarship can result in raised eyebrows. There certainly are blogs which are completely dedicated to scholarly topics, but there are also a very large number of blogs that are personal, or which allow the personal and the professional, the humorous and the serious, not merely to co-exist side by side but intersect and overlap. And anyone who thinks that blogs are by definition diaries unwisely posted in public for the world to read, or begin as scholarly enterprises but unfortunately inevitably lapse into discussions of LOST, pictures of LOLcats and humorous YouTube mash-ups, will inevitably see blogs and scholarship as, if not antithetical, at the very least distinct, and consider it appropriate that they remain so. And for this reason there’s a need to articulate clearly what a blog is, even if it seems tedious and unnecessary to do so.

When I begin with the question “What is a blog?” I am not asking it to insult the intelligence of those present here today, since I assume that anyone who has chosen to come to a session dedicated to blogging has come knowing something of blogs. But neither is my question a purely rhetorical one. I ask “What is a blog?” because, in the mind of many, the term blog has connotations related not merely to form but also content. And I suspect that it may be for this reason that questions about the relevance of blogs to scholarship can result in raised eyebrows. There certainly are blogs which are completely dedicated to scholarly topics, but there are also a very large number of blogs that are personal, or which allow the personal and the professional, the humorous and the serious, not merely to co-exist side by side but intersect and overlap. And anyone who thinks that blogs are by definition diaries unwisely posted in public for the world to read, or begin as scholarly enterprises but unfortunately inevitably lapse into discussions of LOST, pictures of LOLcats and humorous YouTube mash-ups, will inevitably see blogs and scholarship as, if not antithetical, at the very least distinct, and consider it appropriate that they remain so. And for this reason there’s a need to articulate clearly what a blog is, even if it seems tedious and unnecessary to do so.” shows the influence that online mythicist sources can have and how they can end up getting significant attention. I presume that all of us who are involved in education are concerned about both the dissemination of reliable information, and the honing of critical thinking skills. And so, to the extent that online discussions of topics related to our field can at times be typified by approaches that are neither well-informed nor characterized by critical thinking, blogs provide scholars with an opportunity to illustrate both to an audience that will never enter our classrooms or read our articles and books.