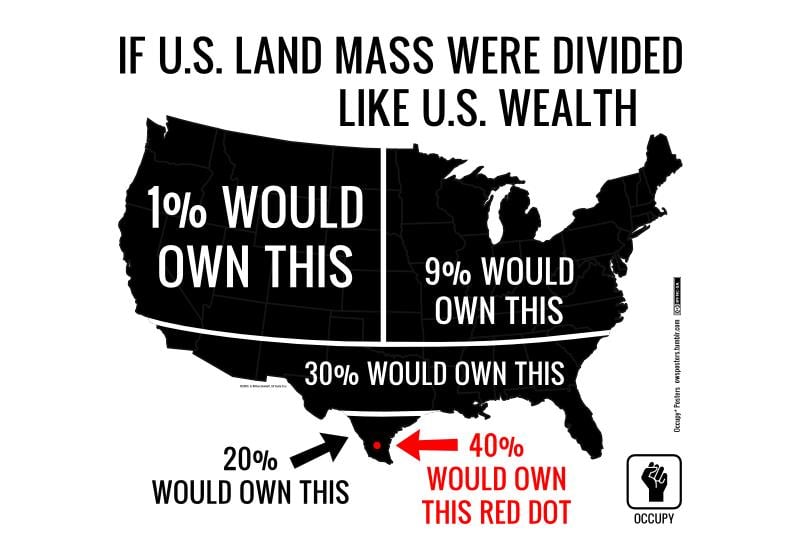

I reposted this image that came my way on Facebook, and it generated a significant amount of discussion.

I find it interesting for a number of reasons, besides the striking illustration of the distribution of wealth in the United States.

It helps make the point that, just as one cannot simply produce more land as a means of addressing the problem of allocation of space, so that everyone can have a state to themselves, the idea that wealth measured in dollars can be infinitely increased is similarly problematic. If, as a result of their hard work or willingness to invest what they have, the government were to print more money so that all became wealthy, it would not work – printing more money decreases the value of that money and results in inflation. But the impossibility of wealth being endlessly created may go unnoticed until one begins to think of wealth not as something abstract but in real terms.

And since it requires an investment of wealth and resources to generate wealth, to the extent that doing so is possible, it is clear that the playing field is not at all level.

The image also got me thinking about the law in Leviticus 25 concerning the Jubilee year. In ancient Israel, a largely agrarian society, land was the crucial commodity. And whoever penned that law came up with a creative solution – one that is neither capitalism nor communism in anything like the modern form. It doesn’t protect personal property rights, except in the sense that your property could not be sold in perpetuity, but that is precisely the opposite of the meaning in the United States today, where the new owner becomes the owner in perpetuity. But it allowed the “market” to follow its natural course freely for the duration of the stipulated 70 years, so that hard work could potentially have a reward. It thus sought to avoid destitution without collectivization. Would that some today would find such creative solutions to our economic and social ills. It does make you wonder – if the writer of that law had lived in our time, when money rather than property was the crucial commodity, how might they have written the law differently? And back then in ancient Israel, if the law was ever put into practice, would there have been people who objected to the implementation of that law as unfair “confiscation” and “redistribution” of their personal property?

Economics is not my area of expertise, and I continue to learn from friends and acquaintances who take the time to comment on things that I share which touch on those topics. I look forward to hearing thoughts from readers of this blog!