In my Sunday school class last weekend, the discussion quickly moved from a discussion of the atonement to a specific focus on whether God suffers or can suffer.

A number of interesting observations were made, but one seemed particularly worth sharing.

A number of interesting observations were made, but one seemed particularly worth sharing.

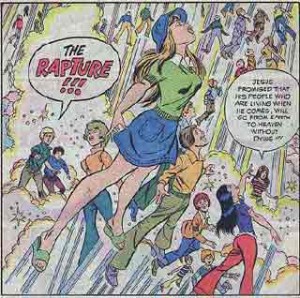

Following a discussion of why some consider it better to be above suffering (and the connections with other persons that cause us suffering) than to suffer (and be connected and in relationship), a retired pastor in the class suggested that there might be a correlation between this and dispensationalism. The conviction that it is more perfect to be above suffering leads naturally to the view that the worthy will be “raptured” and thus spared the tribulation and suffering that they believe is coming upon the world.

I had never thought about it in those terms before. The whole notion of a pre-tribulation rapture reflects the core conviction that it is better for Christians to escape from suffering, than for them to be present in the world, even if their being present would enable them to have a positive impact in a very difficult time, at great cost to themselves.

This tells us something very important about the strands of Christianity that embrace this brand of dispensationalist thinking. The theology turns out to be self-centered, and thus unchristlike in its very essence.

It is possible to conclude, merely from an examination of the evidence, that dispensationalism and the whole futurist approach to Revelation it represents are incorrect and fundamentally misguided. But even as someone who had already drawn that conclusion, and who used to be immersed in his teens in a form of rapture-focused Christianity, it was really a revelation (pun intended) for me to discover just how opposed to the most fundamental principles of Christianity the whole worldview is.

And that relates to another thing that we discussed in my class last Sunday. The church has a tendency to find some external things to focus on, and having avoided them, to proclaim itself to be different from the world. Smoking and drinking are classic examples of these sorts of emblems of conservative church identity. But very often, perhaps almost always, the church turns out on closer examination to be fundamentally like the world, like the culture in which it finds itself, in its core values.

The belief that being free from suffering is better than an existence characterized by suffering, even if the latter is also as a result richer and more beneficial to others, seems to be an example of precisely that: the church resembling the convictions of our culture more than anything inherently or profoundly Christian.