Fred Clark at Slacktivist has posted some thoughts on the Bill O’Reilly conversation with Candida Moss that I shared here recently. In his post he writes:

Moss does not euphemize or equivocate about what the text says that Jesus said or that Jesus said this as a direct assertion of fact. Jesus said that if you don’t give away your wealth to help the poor, then you will go to Hell. Period.

As Keith wrote, O’Reilly’s reaction was typical of “almost all readers of this story … surely that’s not what he really meant.” I think he’s genuinely gobsmacked that Moss, cheerfully but emphatically, doesn’t go along with that. She refuses to play along with “surely that’s not what he really meant.”

And so O’Reilly takes the next usual step — which is also typical for “almost all readers of this story” — and he starts talking about Hell. If Jesus actually said and meant what Moss rightly notes he said and meant, O’Reilly tells her, “then you’re going to Hell and I’m going to Hell and everybody watching is going to Hell!”

To O’Reilly’s credit, the Gospels tell us this was also the reaction from Jesus’ disciples: If what you’re saying is true, then we’re all damned to Hell.

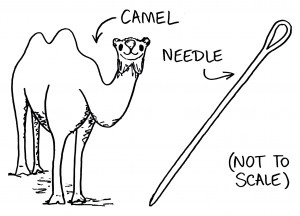

I’ll agree with Keith that what we do with that practically is a separate issue. (Jesus’ reply about camels and needles doesn’t offer much practical relief from the uncompromising moral obligation he’s just laid out.) But I don’t think that what we make of that theologically can be a separate issue. Here is one of the few biblical mentions of Hell and what it teaches us about Hell is utterly incompatible with everything you’ve probably been taught to associate with the idea.

But here’s the remarkable thing — the accidental insight O’Reilly’s aghast response points us toward — every mention of Hell in the Bible is just like this one.

According to the Gospels, Jesus said that it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God. The disciples are depicted as astonished, drawing the conclusion that, if the rich who can afford to practice alms and be generous cannot be saved, then probably no one can. And Jesus’ response is to emphasize that it is indeed a human impossibility – but a divine possibility.

The implications of that are often nullified by Christians. Sure, we insist, there is something that we can do: whether it be trying very hard in some denominations, or reducing what is required to one human action of believing in others. But neither seems to take seriously what the text says: salvation is a human impossibility, but a divine possibility. There is nothing to suggest that human actions can add or assist, or that they can thwart the divine plan.

The question may not be whether the divine aim of transforming humanity can be accomplished, but only how long some of us may resist before ultimately love wins and triumphs over hatred and apathy.

On O’Reilly’s book, see also the 10 reasons why it stinks listed on The Jesus Blog.