I will confess that I tend not to expect certain adamant atheist bloggers to offer nuanced and insightful discussions of matters of religion. And so I want to thank P. Z. Myers for challenging my stereotypes. Here is an excerpt from his recent post, “Palimpsest Jesus”:

And there he is! Palimpsest Jesus! Once you spot him, he’s everywhere. There is no real Jesus — there’s only this blank screen on which people project their imaginary ideals. So Philip Foster sees Jesus as a property rights warrior, a kind of investment banker in robes who thinks inequity is a wonderful thing (Matthew 5, Philip, or Luke 10:30).

And then I spotted him in this interview with Sarah Silverman.

- And to me, I love the symbol of Jesus. It’s so odd to me that so many people on the far right use his name to justify terrible things that I can’t imagine he’d approve of.

And I just want to say to Silverman that he was a first century Jewish rabbi: he probably would have been horrified at openly gay couples, or worse, women speaking and living independent lives. At least she said “the symbol of Jesus”, the tolerant and loving myth, when the reality of Jesus was a man of his time (see Matthew 21and 25:46).

But Jesus has become this foggy dead mysterious authority figure that you can trot out for just about any cause you care about — he’s a regular mercenary who serves any cause, on the left or the right, and can happily serve them at the same time. Abolitionists and slave-holders, pro-choice and anti-choice, capitalist or socialist, he’s right there, manning the barricades and storming them. I tune out any argument that invokes Palimpsest Jesus any more, even ones where I may agree with the side using his name.

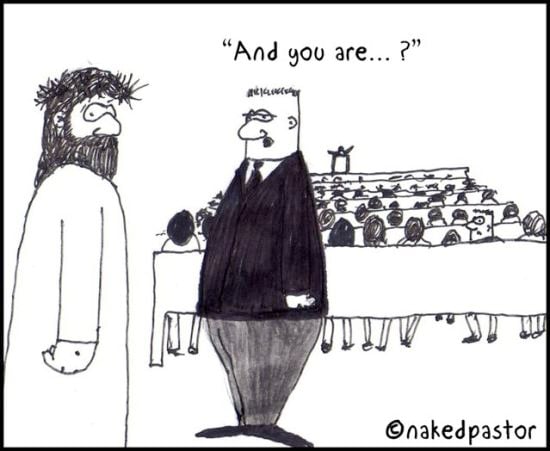

The same day, David Hayward reshared an older cartoon of his, on whether Jesus would be recognized if he showed up in this or that church:

Of related interest, Randal Rauser asked whether God wears a suit and tie when God goes to church.

In some ancient Christian texts, in particular but not only Gnostic ones, Jesus is depicted as changing his appearance. I wonder whether that started with an awareness that people spoke about Jesus in different ways, and an attempt to embrace it all by providing an (admittedly implausible) “rationale”: he was a shape-shifter.

The image of the palimpsest, however, is one that I like better – both because it alludes to the transmission of manuscripts, a key element in our knowledge of ancient Christianity; but also because it reminds that, before one can write whatever one wishes on Jesus as a blank slate, they need to erase what is there. And nothing has hidden the actual historical figure of Jesus from view like this constant erasure and subsequent new composition over the place where the old was once visible.