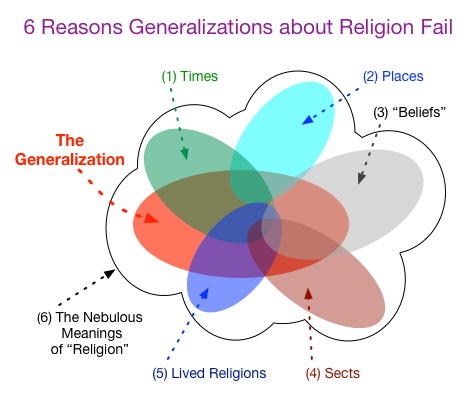

Sabio Lantz has shared some insightful comments about the problem of generalization in discussion of religion. There’s an extensive quotation below, but click through to read the entire post.

Religions around the world nurture conflict and are used as tools for great suffering and nonsense. But religion can also be used in wonderful ways. It is thus a mistake to speak about spiritual and religious traditions as if there existed some coherent, unified, uncontested, unchanging or pristine version of that tradition. Sure, speaking of such an idealized form may be a useful heuristic tool but it is loaded with mistaken notions which become obvious after only the least bit of inspection or dialogue between people who disagree. This error is common with both religion prescriptionists and anti-religion atheists.

Why is this a mistake? Above in my diagram I tried to capture six main factors that make such generalizations sloppy at best. Below are the explanations:

- Times: Historical Varieties of Religion: Religions change over time. So instead of overgeneralizing, we have to specify exactly what time period we are talking about. But for the reasons given below, that is usually not enough.

- Places: Religion Changes by Locality : Catholic Christianity in South America, Italy and the USA vary widely. Even though they may identify a the same sect of Christianity, they have very important differences. Sure, someone may think they share some “essentially” common elements to allow generalizations — but those who hold these faiths may disagree with the lack of importances you put on their differences.

- “Beliefs”: Multivalent “Belief” & Many-Selves: The notion of “belief” is complex. Both the beliefist religionists and the hyper-rational atheists imagine a much more solid thing called belief. We all hold beliefs that contradict each other. We even hold incorrect beliefs, which we nonetheless, use in healthy ways when understood in the web-of-beliefs in which they complexly exist. See my posts on Many Selves and Beliefism.

- Sects: Wide Multitude of Religious Sub-Sects: From Snake-handling Fundamentalists in West Virginia to Mormons in Idaho to Episcopals in Massachusetts the flavors of Christianity vary widely. Their beliefs, practices and exuberance vary a great deal.

- Lived Religions: Variety of Individuals: a given person’s “religion” — that they mean by the word — often has little to do with the doctrines their religious professionals would want them to confess. Instead, may be identity, social relations, tradition, good luck religion, imagined moral framework, holidays and rituals or comfort medicine. And when you ask the individual, they may not only be uniformed of the very religion they identify with, but even hold heretical views or practices (often unbeknownst to themselves). Heck most religious folks don’t even believe a lot of what they confess.

- Nebulous Meanings: Vague Definitions of “Religion”: Even among scholars, there is not agreement on definitions of “religion”. It is used in multiple ways by speakers. And when people use it in a general way, they are imagining some very specific form and practice of religion which their generalization overshoots. See my post on Defining Religion.

You may feel you have sufficient objections to any one of the above bullets and thus feel justified in your essentializing, reifying and objectifing some spiritual or religious tradition in a general way, but you need to consider all the bullets and their interactions. Propagandists and prescriptionists are not interested in this complexity — usually because they feel it cripples their mission, but this blog is about complexity and clear thinking, not convenient rhetoric.

Conclusion:

To begin, when speaking of any Christianity, use adjectives to specify which subset you are talking about. But even then, realize that you can not list enough adjectives to be careful enough. So, be careful in your generalizations and try to reflect on why you are generalizing, essentializing and reifying such an abstract notion.

Vehement, anti-religion atheists are committed to disparaging the word “religion” and so all the subtlety above is mere distraction from their mission. They will not give in an inch — nothing will stop their unscientific gross over-generalizations. Though the above information is common sense among most anthropologists and sociologist who would never generalize about religion. These atheists ironically care not for a scientific approach when it conflicts with their evangelical efforts.