The rules of grammar are often flouted by those who do not know them. But they are also often misunderstood by those who judge people who express themselves in ungrammatical ways.

There is no static grammar, because languages evolve. There was a time when languages were rarely written, and even today speaking is more common than writing. We have developed spelling conventions so that words are written consistently. But there was a time when one might regularly find the same word spelled in many different ways.

This is because the use of letters in writing is a symbolic representation of the spoken word. All the words that I have used thus far in this post, all the grammatical rules and spelling conventions followed, are not something absolute or static. In a few hundred years, aspects of what I have written here (assuming my words were still around somewhere) will seem archaic and odd.

This is because the use of letters in writing is a symbolic representation of the spoken word. All the words that I have used thus far in this post, all the grammatical rules and spelling conventions followed, are not something absolute or static. In a few hundred years, aspects of what I have written here (assuming my words were still around somewhere) will seem archaic and odd.

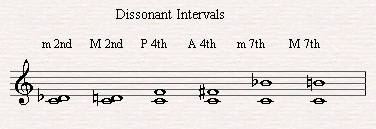

Music provides a useful analogy. Some people learn basic rules of music – keys, scales, chords – and then feel puzzled at the notes and chords a composer included which are not in the key in question.

But the “rules” of music are like the rules of grammar. They are a codification about what sounds good to the ear, not a straitjacket in which sentences or melodies are placed as a prelude to their incarceration, should they play fast and loose with these conventions too often.

The reality is that you can invert words in poetry, and add chromatic passing tones in song, and as long as the listener can understand and enjoy what you have expressed, then you have communicated.

Religion is the same. If someone claims to be a Christian and holds no view that bears any resemblance to anything connected with that tradition, they will simply get puzzled looks. But those who claim that a religion is like a strict set of grammatical or musical rules that cannot be broken has misunderstood religion, grammar, and music.

The prophets and radical theologians, but also the conservative preachers and teachers, not to mention the composers of hymns and choruses and cantatas, all work within frameworks, and multiple frameworks at that. The only things that constrain them in any strict sense are the limits of their imagination on the one hand, and what their audience can bear on the other. One can put together strings of words or musical intervals in an entirely surprising order. The question is whether your hearers will find it meaningful, or mere dissonant nonsense of a sort that a child with no musical education could make by banging on an instrument.

The future of language, music, and religion is determined by those who press the boundaries. They either carve out new space that people come to inhabit, whether speedily or slowly, or otherwise they discover that certain ideas are not received. What they produce may still be meaningful to themselves as the one who composed it, and perhaps to a small circle. And so there is no standpoint from which someone can say “that isn’t language, it isn’t music, it isn’t religion.” There is no objective standpoint from which to judge such human creative activities. But societies judge nonetheless, and those who wish not merely to express themselves but to influence their world cannot ignore the reactions offered to their compositions. They must rather walk the fine line between tradition and innovation, between order and chaos, while also seeking to chart a new path and hoping that some may follow them.

There is therefore no use insisting that people who adopt a different view about a theological or a moral question than the traditional one in their past are “not being faithful to their religion.” That is like saying that e. e. cummings was not being faithful to the English language. He walked the boundary between rigid adherence to rules and flexible creativity. It is like saying that jazz “isn’t being faithful to music” – or worse still that it isn’t music at all – because its extensive chromaticism and dissonance would surely have baffled Haydn.

As for whose work today will set the tone for the music or the religious beliefs and practices of tomorrow, only time will tell.

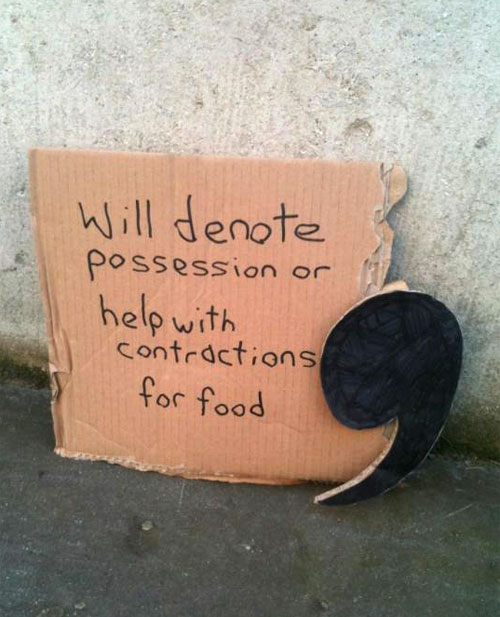

Just keep in mind when considering the matter that, viewed from a future in which the apostrophe has been eliminated, those who did not use it in the early 21st century would not seem like uneducated and ungrammatical imbeciles, but pioneers ahead of their time, people who wrote in ways that people in the 25th century find more intelligible across the centuries than those odd educated authors who stuck odd little floating commas in their words.

Just keep in mind when considering the matter that, viewed from a future in which the apostrophe has been eliminated, those who did not use it in the early 21st century would not seem like uneducated and ungrammatical imbeciles, but pioneers ahead of their time, people who wrote in ways that people in the 25th century find more intelligible across the centuries than those odd educated authors who stuck odd little floating commas in their words.

But of course, we cannot know from now that that is what the future of language holds. And so neither those who are more traditional nor those who ignore the rules can claim from now to be speaking the language of the future, or playing the music of the future, or living out the Christianity of the future.

They can only do as their convictions and conscience dictate, ignoring their critics if necessary, and offer a vision that they hope will catch on.

After that, only time will tell.

Let me close by mentioning a saying attributed to Jesus in one manuscript of Luke’s Gospel (Codex Bezae), in Luke 6:5. In it, Jesus is said to have found someone working on the Sabbath, and to have said, “Friend, if you know what you are doing, you are blessed; but if you do not, you are accursed as a breaker of the Law.”

You have to know and understand the rules, to be able to break them in ways that are not merely ignorant, but meaningful and creative.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fneAE1vly1o